America’s concentration camps.

I’m a Jewish Historian and, Yes, We Should Call Border Detention Centers “Concentration Camps.” It isn’t just accurate. It’s necessary.

Anna Lind-Guzik / Vox

(June 20, 2019) — This week, conservatives weaponized Jewish suffering to divert discussion from the massive human rights abuses occurring at our border.

Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY), daughter of the man who called torture “enhanced interrogation,” scolded Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) for using the term “concentration camp” to describe the growing civilian detention system, including the reopening of Fort Sill, previously a Japanese American internment camp, to hold children.

Since then, Jews have split on whether it’s appropriate to use “concentration camp” outside the context of the Holocaust. There are those who find the term too emotionally charged, or who believe the sheer scale of the Nazi Final Solution bars any possible comparison.

Though I disagree, I understand. My father turned seven on June 22, 1941, the day the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. I was raised with the story of how my grandmother saved my dad and aunt with her quick thinking and a cramped spot on a cattle train leaving Odessa for Siberia. Those who remained were shot. As a Jew, I bear witness to the memory of those who did not survive.

I’m also a legal historian, and my research on genocide and crimes against humanity has made clear that while the Holocaust is unique in its scale and implementation, the perpetrators and motivations are not. Genocide is a human crime, not a German one. In the wake of World War II, human rights laws were written in the hopes of preventing future tragedies, not for labeling the past.

First, it’s important to note that despite the contemporary association of concentration camps with the Shoah, they are not a Nazi invention. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, various imperial forces — including the British and Germans in their African colonies, the Spanish in the Caribbean, and Americans in the West — engaged in the practice of rounding up civilians into concentration camps as a tactic to suppress indigenous guerrilla warfare. By isolating the civilian population, fighters had fewer places to hide. Large populations of mostly women and children were held in terrible, quasi-permanent conditions, without trial, and died en masse from disease, malnutrition, and exposure.

Historian Isabel Hull argues that the German military’s predisposition toward “final solutions” was first evident in the 1904 internment and genocide of the Herero and Nama people in the German colony of South West Africa, now Namibia, in what was already called a “concentration camp.” The term itself comes from reconcentración,a Spanish policy deployed against Cubans in the 1890s, which was then reused by the British during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902.

Meanwhile, Americans offended at the use of “concentration camp” should acquaint themselves with our own history of civilian detention. As early as 1862, American forces interned Dakota women and children at Fort Snelling. George Takei tweeted this week regarding the mass internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, “I know what concentration camps are. I was inside two of them, in America. And yes, we are operating such camps again.”

Applying the term “concentration camp” to the indefinite detention without trial of thousands of civilians in inhumane conditions — under armed guard and without adequate provisions or medical care — is not just appropriate, it’s necessary. Invoking the word does not demean the memory of the Holocaust. Instead, the lessons of the Holocaust will be lost if we refuse to engage with them.

If conservatives truly think that “concentration camp” is limited to Nazi death camps, where was the outrage when the Trump administration employed it to (correctly) describe the mass detention of Uighurs in Xinjiang? (Naturally, the Chinese government also hates the term concentration camp, preferring to call them “vocational education training centers.”)

Apart from the historical argument, there is a moral and geopolitical imperative for calling the atrocities happening on our southern border by their proper names. The international human rights regime depends on global cooperation, a veneer of accountability, and American funding. Trump eschews soft power in favor of military solutions, and is leading his fellow authoritarians in a race to the bottom.

The 1951 Refugee Convention, while imperfect, once offered protections to stateless, persecuted people. That’s no longer true. Asylum seekers at the Mexican border are being treated like criminals despite having broken no laws. Locking up refugees in camps is the real betrayal of the legacy of the Holocaust.

As Hannah Arendt taught us in Eichmann in Jerusalem, perpetrators depend on us being desensitized to the victims’ suffering. Using euphemisms to cover for atrocities is the essence of the banality of evil. This is why perpetrators work so hard to propagandize, criminalize, and dehumanize the Other. Authoritarians require enemies to blame for their inadequacies, and to distract their base from their diminishing quality of life.

The red flags at the border are obvious to those of us raised with “never again,” a phrase Ocasio-Cortez invoked: dehumanizing language, children in cages, families separated, the deaths of trans asylum seekers, rampant diseases, and subhuman living conditions.

“Never again” means we must work to deescalate before atrocities rise to the horrors of Auschwitz. Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Israel, was upset with Ocasio-Cortez for invoking the term, yet its own materials note that concentration camps for undesirables, including Jews, Poles, Communists, gay people, and Roma, opened in 1933, while the death camps were opened starting in 1941.

It’s tragic that Yad Vashem, an institution I’ve venerated and visited, has opted to chasten a young woman for calling out crimes against humanity that mirror what Jews endured less than a century ago, at the same that it embraces visitors like Viktor Orban, the anti-Semitic, ethnonationalist Hungarian prime minister.

In memory of the 6 million Jews who perished because they were considered less human, I will not accept my government treating migrants like animals. And as the daughter of a Soviet Jewish refugee, I will not accept the criminalization of stateless people. Perpetrators depend on complacency, on our inability to care for people unlike ourselves. No person is illegal, or a pest to be exterminated. If you don’t like the term concentration camp, help close them.

Anna Lind-Guzik is executive director of the Conversationalist. She is a writer, attorney, and scholar of Soviet history, international law, and human rights, with degrees from Duke University, Harvard Law School, and Princeton University. Follow her on Twitter @alindguzik.

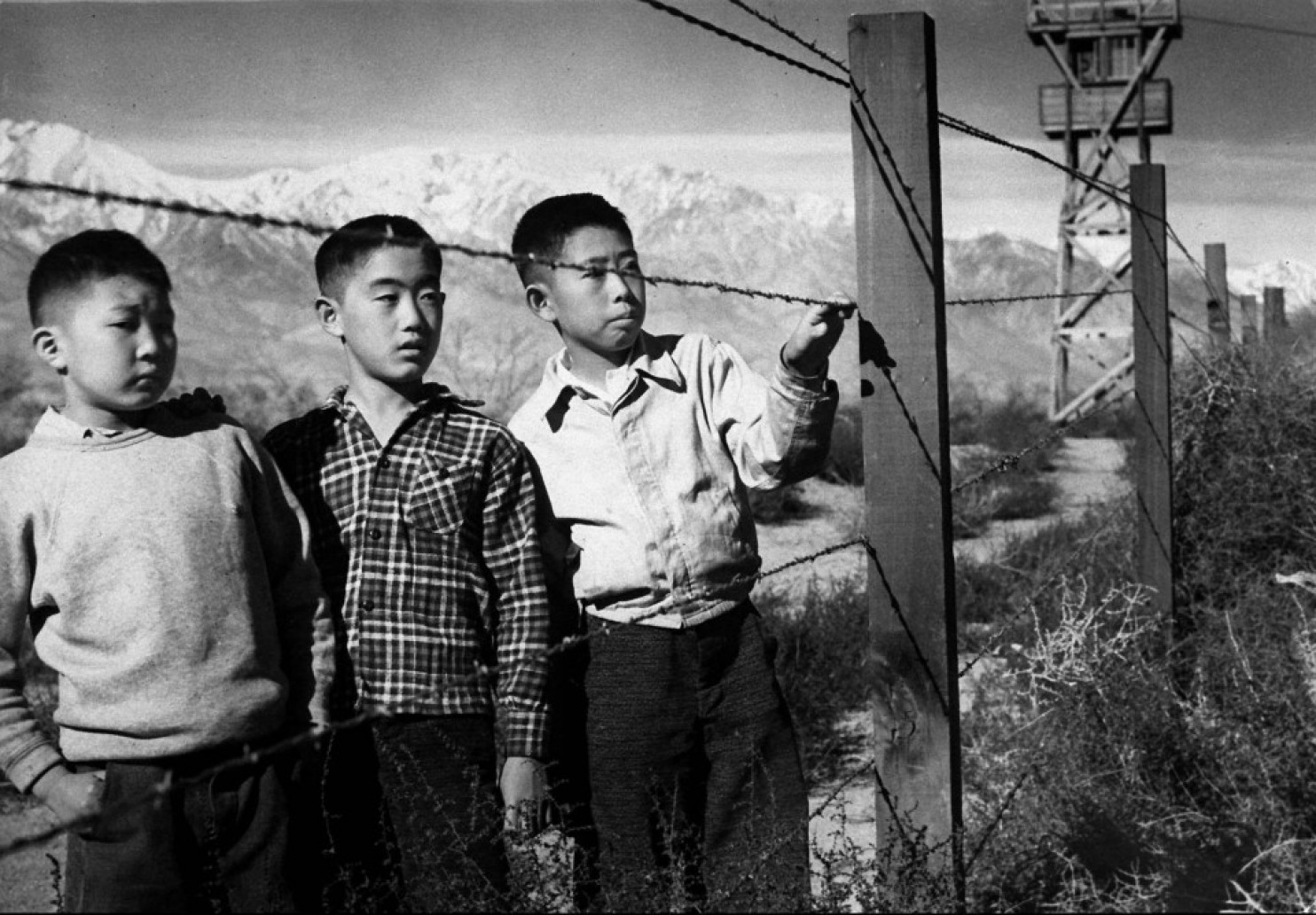

Japanese-American children confined in US concentration camps during WWII.

Japanese Internment Camp Survivors Protest Ft. Sill Migrant Detention Center

Molly Hennessy-Fiske / The Los Angeles Times

(June 22, 2019) — With the Trump administration planning to move 1,400 migrant children to this fortified Army post later this summer, a small group of Japanese American World War II internment camp survivors came to the gates Saturday to make their opposition known.

“We are here today to protest the repetition of history,” proclaimed camp survivor Satsuki Ina, 75, of San Francisco, one of about two dozen former internees and their descendants in attendance.

Met by uniformed military police, the protesters, some in their 80s, were told they did not have permission to congregate and might face arrest. “You need to move right now!” one of the officers shouted. “What don’t you understand? It’s English: Get out.”

But the survivors, carrying thousands of origami cranes as a symbol of solidarity, refused to leave until police from adjacent Lawton, Okla., arrived and let them speak. They then moved to a park where a crowd of about 200 was waiting.

Ft. Sill has become a rallying point for Japanese Americans hoping to prevent migrant detention in what they call concentration camps, some built on the sites where they and their families were interned during World War II.

About 120,000 Japanese Americans, including families and children, were held at about a dozen camps during the war, some for years. Italian and German Americans were also held at the camps, built in remote Western outposts.

The Ft. Sill post has now been designated an emergency shelter and is due to house children who have crossed the border from Mexico unaccompanied by adults. The post was last used to house migrant children in 2014, when it took in 1,861.

By law, the Border Patrol can hold such children for up to 72 hours and must then turn them over to Department of Health and Human Services officials, who place them in a network of 168 detention centers in 23 states.

Those lockups have filled, leading the agency to add a 2,400-bed facility in Homestead, Fla., as they have for the last two years. Officials plan to open the Ft. Sill lockup this summer, and a 1,600-bed facility at a former oilfield worker housing complex in Carrizo Springs, Texas, later this month, near the site of the World War II internment camp of Crystal City.

In all, federal officials are opening tents and emergency lockups for an influx of nearly 600,000 migrants on the southern border this year, mostly families and children unaccompanied by adults, many from Central America.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has crammed 15,000 migrants into temporary holding areas designed for only 4,000 people. On Friday, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott announced he was sending 1,000 National Guard troops to the border, doubling the number deployed, to assist at temporary holding areas. The Border Patrol has asked Congress for emergency funding to care for migrants, and a $4.5-billion House proposal is scheduled for a vote in the coming week.

During the Obama administration, Oklahoma’s Republican leaders opposed lockups such as Ft. Sill, but they are now defending them. Sens. James M. Inhofe and James Lankford joined Rep. Tom Cole, also of Oklahoma, to issue a joint statement calling the facility a necessary, temporary solution to the border crisis.

Lankford said in a separate statement last week that to liken the migrant detention centers to internment camps “is a false equivalency.”

“What happened then is not what is happening now,” the statement said. “… Every country now knows if you come into our country with a child, you will be released. It is our responsibility to ensure the security and safety of all the children coming into our country, and I have confidence that will be done properly at Fort Sill.”

Ft. Sill has a particularly dark history, which Seattle-based historian Tom Ikeda recounted at Saturday’s gathering.

Founded in 1869, the post has hosted a relocation camp for Native Americans, a boarding school for Native children separated from their families, and an internment camp for 700 Japanese American men in 1942. Saturday’s crowd included former students from the boarding school and descendants of Ft. Sill detainees.

Among those once interned at Ft. Sill was Kanesaburo Oshima, fatally shot by guards while scaling the post’s fence. Ikeda, who interviewed Oshima’s son, shared the story of Oshima — a 58-year-old businessman and father of 11 from Kona, Hawaii — with the group on Saturday.

“We need to be the allies for vulnerable communities today that Japanese Americans didn’t have in 1942,” Ikeda said.

Paul Tomita and other internment camp survivors brought camp ID cards and other photos of themselves from when they were detained as children.

Tomita, 80, of Bellevue, Wash., was sent to a camp in Idaho when he was 3, and his family lived in a dusty tent there for about a year. He said Saturday that when he sees photographs of detained migrant children, he recognizes a sense of despair. “It’s our responsibility to help,” he said.

Last week, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) faced a backlash when she called migrant detention facilities concentration camps and refused to back down.

“We are calling these camps what they are because they fit squarely in an academic consensus and definition,” she tweeted.

Critics say the term applies only to the Nazi death camps where millions of Jews were killed. But some descendants of Holocaust survivors who gathered at Ft. Sill disagreed.

Mike Korenblit’s parents survived a concentration camp in Poland. Now Korenblit, 67, and his wife, of Edmond, Okla., protest regularly outside their local Immigration and Customs Enforcement office. He wore a U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum T-shirt to Saturday’s protest and defended using the term “concentration camps” for internment camps and migrant holding areas.

“They are the same kind of situation. Why aren’t they identified as the same thing?” he said.

Karen Ishizuka, senior curator at Los Angeles’ Japanese American National Museum, was forced in the 1990s to defend her use of the term for internment camps when she organized an exhibit called “America’s Concentration Camps: Remembering the Japanese American Experience.”

“To call them anything else is to mitigate the enormity of the travesty,” she said before Saturday’s protest.

Pressured in the ’90s to change the name before the exhibit opened, museum officials met with representatives of Jewish groups, drafted a joint letter and successfully mounted the exhibit. “A concentration camp is a place where people are imprisoned not because of any crime they have committed, but simply because of who they are,” the 1998 statement said.

Museum officials sent Ishizuka to Ft. Sill on Saturday and plan a second protest in front of the museum in Little Tokyo on Thursday.

Ishizuka said Saturday’s protest had personal significance: Four of her uncles fought in the U.S. Army during World War II, even as other relatives were held at the camps.

“We all have the responsibility to stand up for justice,” she said.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.