A Young Girl’s Blood in Yemen’s Sand

Daily Kos, Demand Progress and Just Foreign Policy

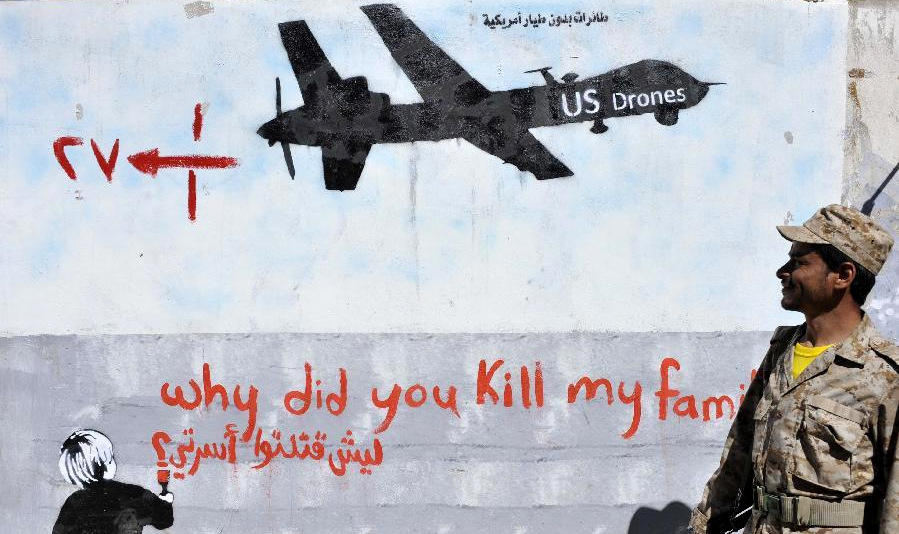

(October 15, 2019) — Blood dyed the sand black within minutes. That’s how a recent Guardian profile described a drone strike in Yemen last year that horrifically killed Raja Hamid Yahya al-Oud, a 14-year old girl. [Read the complete Guardian article below — EAW]

The ammunition dropped from the sky, so high up that young Raja never saw what killed her, was manufactured in right here in the United States and later sold to the Saudi-led effort that has claimed thousands of lives in Yemen.

This is the brutal, graphic cost of US-involvement in the war in Yemen. Thankfully, you can help stop it, but time is running out: we have just a few weeks left to ensure that a key defense spending bill outlaws US arms sales to Saudi Arabia for the Yemen war, and we need you to act now.

Tell Congress “no more blood in the sand” — it’s time to stop funding the war in Yemen.

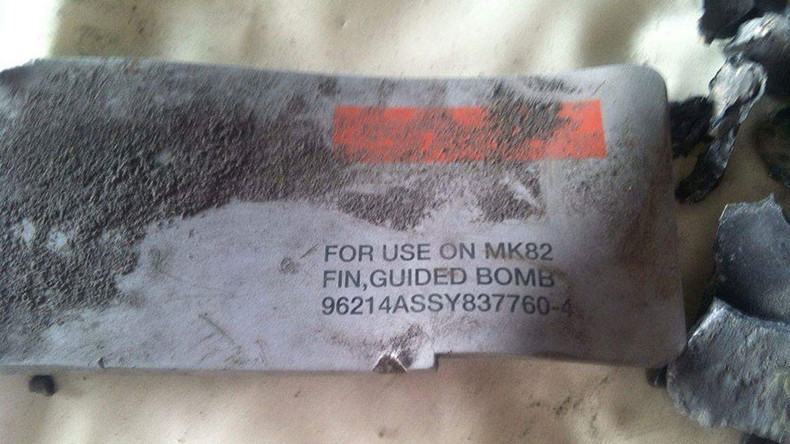

The recent Guardian article used the bomb’s serial numbers to map the story of one girl’s death back to its origins: US soil. The picture they paint is gruesome.

For four years, the US has equipped Saudi forces with intelligence for drone strikes, weapons, and ammunition. And in return, Saudi-led forces have bombed Yemen, killing thousands of Yemeni people and plunging millions more into the brink of starvation.

This is the same government that brutally murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and the same government that has become one of Trump’s key allies. But we have real momentum in Congress to stop this horrific partnership against the people of Yemen.

Right now Congress is debating a massive military bill called the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The House passed a version of the NDAA with crucial amendments that cut off US support for the war in Yemen. The Senate, however, did not. Now, both chambers have to come together to hash out the final bill, and that’s where you come in.

As a constituent, your members of Congress can’t ignore you. Your voice will be crucial to ending US support for the war in Yemen, and potentially saves thousands of lives.

ACTION: Tell Congress: “No more blood on the sand” — it’s time to cut US funding for the war in Yemen.

Thanks for taking action,

The team at Demand Progress

American-made ammunition fragments found after attack on a civilian funeral ceremony in Yemen.

Demand Congress Stop Funding the War in Yemen

Demand Progress

(October 15, 2019) — The people of Yemen, and others throughout the region, are suffering from human rights violations at the hands of the Saudi and Emirati governments, aided by Trump. The US provides funding to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who continue to fight the Houthi rebels in the country.

A recent United Nations investigation into the civil war in Yemen found that multiple parties have repeatedly engaged in possible war crimes, including targeting civilians with airstrikes, artillery and snipers, arbitrary detentions and killings, torture, sexual violence, and impeding access to humanitarian aid. The same report finds countries that fund this war, including the US, to be complicit to war crimes!

The US must withdraw support and help end this war. We must stop supporting war crimes!

Trump has vetoed five bills this year — four of them have dealt with US support for the Saudi and UAE monarchies and their role in the now four-year-old brutal war and humanitarian nightmare in Yemen.

Congress’s next move will come in September, when the House and Senate will meet to finalize a version of the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). A conference committee of Representatives and Senators is meeting right now to hash out the final details. But this legislation must include House amendments aimed at limiting the US war in Yemen, and prohibiting US arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates related to this war.

We must urge the Senate to stop funding this inhumane war. Defunding the US military involvement in the war in Yemen could bring the four-year struggle to an end.

THE LETTER

The UN investigation into the civil war in Yemen found that multiple parties have repeatedly engaged in possible war crimes. We are funding these war crimes.

I urge you to cease funding this war. Hundreds are dying, including children, at the hands of the US Pulling US funding would end this inhumane war that has dragged on for four years!

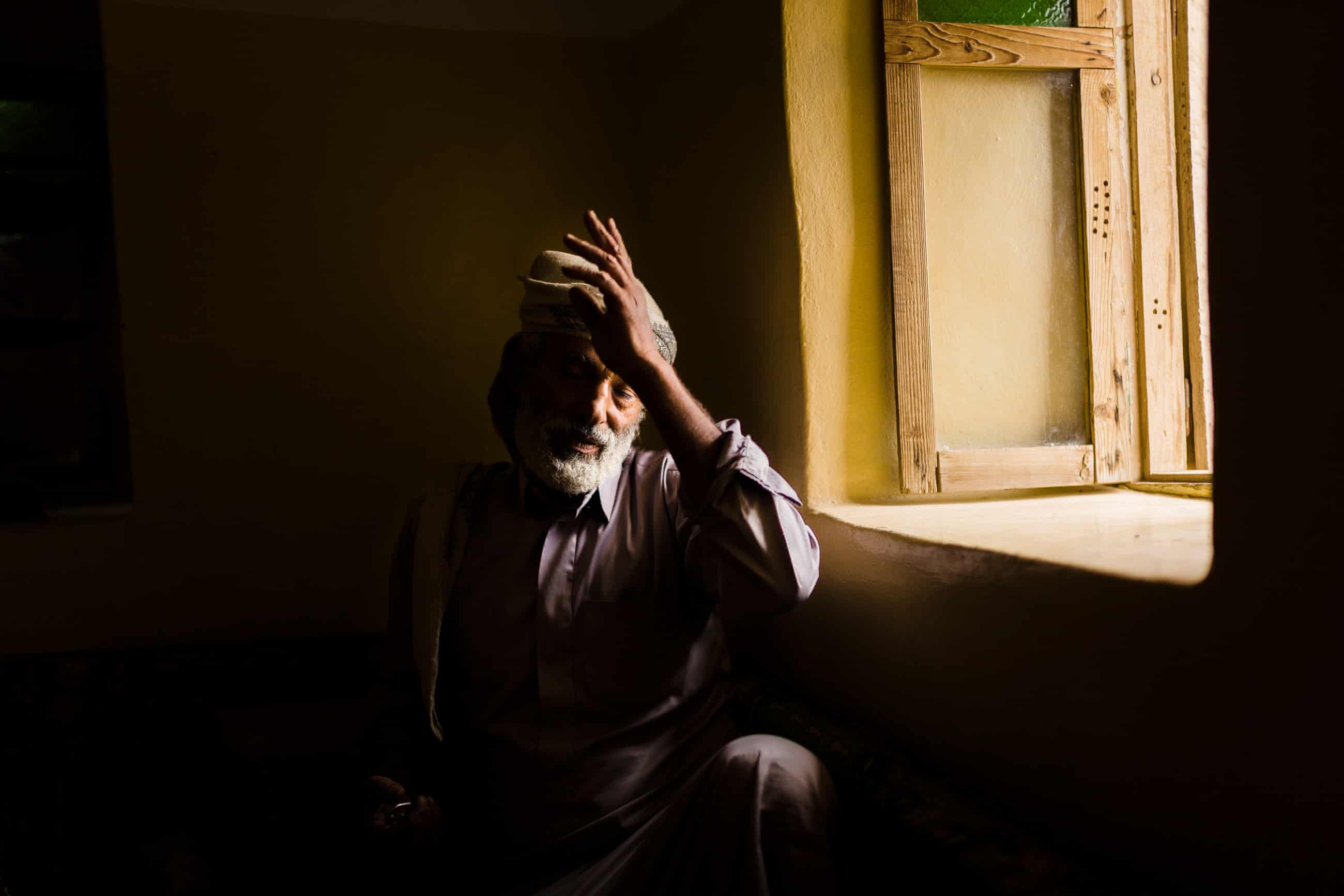

A Father’s Grief and the Made-in-USA Bomb That Killed His Daughter

Bethan McKernan / The Guardian

Cluster bombs, a type of munition invented by the Nazis to kill as many as possible, were used in coalition strike on a Yemen farm that killed Raja, 14

SAADA (October 3, 2019) — The last day of 14-year-old Raja Hamid Yahya al-Oud’s life began like any other.

She got up early along with the rest of the family because there was always a lot of work to do on the farm in the spring planting season. White drones had intermittently circled above their cornfields for the last few weeks, but there was no sign of them that morning.

Raja and her mother, Amira, liked to take breaks under the acacia trees about 200 metres from the house. At 4pm, this was to become her final resting place.

The plane was flying too high for them to hear it coming but Amira said the sound the CBU-52 B/B cluster bomb made as it rained 220 deadly submunitions on their heads will stay with her forever. Some exploded on impact while others, still armed, fell into the fields.

Screaming for her daughter, Amira saw Raja’s twisted body under a small tree. Her jaw and entire right side had been ripped apart and blood had already dyed the sand around her black. A neighbour, Hamoud Mohammed al-Ghar, dodged the remaining submunitions to pick Raja up and then ran with her to the nearest road to find a car to take her to hospital. “I knew the girl was already dead,” he said. “But I had to try.” The drones circled ahead the entire time.

Raja died on 23 March 2018. But the story of the bomb that is believed to have killed her stretches back decades earlier. Using the serial number and other technical information on the CBU-52 B/B’s outer shell, the Guardian traced the munition from its manufacture in Milan, Tennessee, to Sahar farms, in north Yemen, where it ended a child’s life.

They usually consist of a hollow shell filled with hundreds of submunitions that disperse over an area as big as several football pitches as it falls through the air. They either explode on impact or are triggered when moved or stepped on, firing hundreds of fragments of metal that travel at the speed of bullets.

The submunitions remain a threat for decades once deployed and those from older designs often resemble shiny silver orbs around the size of a tennis ball, making unexploded ordnance especially attractive to curious children. Hundreds of people worldwide die each year after coming into contact with unexploded cluster bombs, with about 300 casualties a year in Vietnam alone.

In 2008 an international treaty called the convention on cluster munitions severely limiting the use, transfer and stockpiling of cluster bombs was adopted by 30 countries. By 2018 it had been signed by 120 states. The US, which sells arms to Saudi-led forces fighting in Yemen, was not one of them.

“Cluster munitions went through a proportionality test to measure military advantages gained versus civilian harm of their use,” said Rawan Shaif, the lead Yemen researcher at the open source investigative organisation Bellingcat, of the Geneva conventions relating to the protection of victims of armed conflict. “There’s no military advantage in using a cluster munition in a farm, unless your aim is to make that area uninhabitable for generations of civilians and military alike.”

The cluster bomb that killed Raja was manufactured at the Milan Army Ammunition Plant in 1977. The large site, just north of Jackson in west Tennessee, encompasses 231 miles (372km) of roads and 88 miles (142km) of railways and is nicknamed Bullet Town by residents.

Milan’s fortunes have risen and fallen with that of the plant: work there has ebbed and flowed with America’s wars. Most of its ordnance and mortar production lines have been moved to Iowa by American Ordnance, the private contractor operating the plant. In 2013 it employed just 113 people, down from a peak of 10,000 during the second world war. By 1977 thousands of cluster bombs like the one that killed Raja were rolling off the production line.

The US no longer manufactures CBU-52s: it has long since upgraded to “smart” computer-guided cluster bombs with supposedly more accurate arming and targeting systems. One possible reason a 1977 bomb found its way to Sahar farms, in Yemen, in 2018 is because the US has such a large stockpile of the weapons.

While other countries were adopting the international convention on cluster munitions in 2008, the Pentagon defended its use of them as a “military necessity”. However, it conceded to international criticism by instituting a policy to reduce the failure rate of the munitions – ie the amount of unexploded ordnance left behind – to 1% or less after 2018, although that policy was actually scrapped by Donald Trump 2017.

In the interim, a good way of reducing the stockpile of outdated weapons – and making some money – was to sell them. Data from 2017 showed the US still had some 2.2m cluster bombs in its arsenal.

“Many nations, including the US, Germany, and Switzerland, have taken steps in recent years to bolster both their pre-export due diligence, and their post-delivery verification methods,” said Nic Jenzen-Jones, the director of Armament Research Services, a specialist technical intelligence consultancy. “Nonetheless, there are a lot of arms that have been exported prior to these changes that muddy the waters in terms of how researchers can track and trace items of interest.”

The US has been selling weapons, planes, tanks and ordnance to Saudi Arabia for decades and permitting its arms manufacturers to export: it has licensed $138bn (£112bn) to the kingdom in the last 10 years alone, according to research by the US thinktank the Center for International Policy. Officials under Barack Obama worried that sales, after Riyadh launched its air campaign against Yemen’s Iran-backed Houthi rebels in March 2015, could amount to complicity in war crimes under international laws that could name the US as a co-belligerent, but in 2016 went ahead with a $1.3bn sale anyway.

Bomb sales continue: Donald Trump, who has made Saudi Arabia the cornerstone of his Middle East policy, overrode objections from Congress in March to complete the sale of more than $8bn worth of weapons to Riyadh, its coalition partner the United Arab Emirates coalition partner, and Jordan.

The total extent of export licences to the kingdom is not known, and neither is it known when the bomb that killed Raja was sold. The SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, the world’s most extensive record, yielded no results: it contains just a fraction of true sales, as pre-digital record-keeping was poor and states cite national security concerns to avoid disclosing records.

It is possible the CBU could have been sold by the US years ago to a third party state and then sold on again to Saudi Arabia: cluster bomb sales to Riyadh were officially stopped in 2016. The US Department of Defense and the state department did not respond to requests for information. Such inquiries are usually met with no comment.

Washington says US supplies of “smart weapons” are helping the coalition reduce civilian casualties – but as Raja’s death shows, old US-made dumb bombs are still being used.

What we do know is Sahar farms was bombed on 23 March last year after the area had been surveyed by drones for weeks. “We are just farmers,” Hamid Yahya al-Oud, Raja’s father, said over tea in his living room, surrounded by his six remaining children. “Look outside. There’s our well, there’s our goats. Why would there be Houthis here?”

At the time of publication, the coalition had not responded to the Guardian’s requests for comment.

Sahar farms lies in the countryside of Saada in north Yemen, the Houthi heartland on Saudi Arabia’s border. The whole province is littered with bombed-out buildings, bridges, roads and unexploded ordnance. The green cigar-like shell of the CBU-52 B/B cluster bomb is one of the most common of those dropped on the area, according to Abdullah Umayyad, the manager of the UN-funded Yemen Executive Mine Action Centre (Yemac) field office in Saada.

The coalition rarely acknowledges civilian casualties from airstrikes, making justice or even simple answers for affected families about why they were targeted almost impossible.

“It took two days to clear out Sahar farms after that strike,” said Umayyad. “The work is very dangerous. Three men have been killed in clearance operations here in Saada. My old boss lost his hands, eyes and nose after trying to disarm a cluster bomb submunition last year.”

Despite condemnation from human rights groups over airstrikes in Yemen, Yemac’s records suggest more cluster bombs are being dropped on Saada than ever: at least 147 cluster munitions were recovered in the province in the first six months of 2019, up on 122 in the same period of 2018.

Its record-keeping, however, is spotty and individual items are not catalogued. Questions of who, what and why when it comes to bombings fall outside its remit: the political fallout could impact the team’s ability to work across the war-torn country.

US-made bombs rain down on north Yemen with almost total impunity.

At Sahar farms, the drones have been back in the last two months. “They already killed my daughter,” said Hamid. “Now they’re back for more.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes