30 Years Ago in El Salvador, US-Trained Soldiers Murdered 6 Priests in Cold Blood

November 16 marks thirty years since the massacre of six Jesuits, their housekeeper, and her daughter by US-trained forces. But US brutality in Latin America isn’t a thing of the past: top military officials involved in the coup against Bolivian president Evo Morales were trained by the United States, too.

(November 16, 2019) — In November 16, 1989, six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter were murdered in their residence on the campus of the Jesuit Central American University (UCA) in San Salvador, El Salvador. Thirty years later, the massacre remains emblematic of the indiscriminate savagery exercised by the servants of the Salvadoran ruling class, the impunity they enjoy, and the devastating legacies of US intervention in the region.

The Jesuit murders drew international outcry, but the victims were only eight of some seventy-five thousand killed and ten thousand more disappeared during the twelve-year civil war (1980–1992). Formally, the conflict pitted the US-backed military dictatorship against the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) leftist guerillas. But the Salvadoran state tortured and slaughtered civilians with abandon.

At the war’s close, a 1993 United Nations Truth Commission report attributed only 5 percent of the bloodshed to the insurgents. The regime and its paramilitaries bore responsibility for the vast majority of the conflict’s deaths, disappearances, and displacements.

The Salvadoran security forces didn’t carry out these horrors alone. They were armed, trained, funded, and advised by the United States. The attack at the UCA was carried out by members of the Atlacatl Battalion, an elite counterinsurgency force trained at the infamous School of the Americas (SOA) in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Several members of the military high command who gave the orders and participated in the cover-up were also graduates of that illustrious institution. The best way we can honor the victims of the Jesuit massacre and US-backed atrocities worldwide today is to stop them from recurring by severing the global tentacles of US empire.

The War

El Salvador’s civil war was the result of decades, indeed centuries, of dispossession and exploitation of the country’s impoverished majorities at the hands of a handful of landed oligarchic families. The military regime quashed a 1932 indigenous and Communist uprising with genocidal violence, and peaceful movements for democratic reforms and redistribution were met with brazen electoral fraud and escalating force throughout the 1960s and ’70s. Salvadoran students, unionists, and peasants increasingly turned to arms, eventually formalizing the FMLN in 1980.

Following in the footsteps of Nicaragua’s Sandinistas, the guerillas would have soon overwhelmed the antidemocratic regime were it not for US intervention. Reagan and his neocons, determined to prevent another revolutionary victory in the region, propped up the embattled dictatorship to the tune of up to $1 million per day. All the weight of the US empire could not defeat the rebels, who fought the regime to a draw in 1992.

The prevailing wisdom of Latin American insurgent strategy held that El Salvador’s small, densely populated terrain could not sustain guerilla warfare, but the FMLN proved otherwise. The insurgency’s remarkable success among rural peasants was made possible in part by the gains of radical, new forms of Catholicism in the countryside, with clandestine organizing made possible often by close coordination with local clergy.

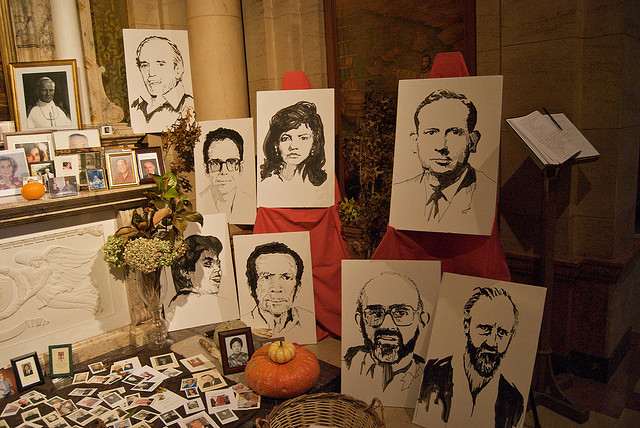

The Martyrs

The UCA’s Jesuits were among some two dozen priests assassinated throughout El Salvador’s civil war by Salvadoran security forces or their associated death squads. Prominent victims included Father Rutilio Grande, murdered with two parishioners in Aguilares in 1977; Saint Óscar Romero, archbishop of San Salvador, gunned down while delivering mass in 1980; as well as Ita Ford, Dorothy Kazel, Jean Donovan, and Maura Clarke, four US churchwomen raped and murdered later that same year.

Many of these martyrs were practitioners of the Catholic doctrine of liberation theology, which emerged following the 1959 Second Vatican Council and 1968 Medellín Conference of Latin American Bishops. Inspired by the emancipatory struggles of the time, liberation theology advocated a “preferential option for the poor” and critiqued the “structural sins” of capitalism and colonization.

For Latin America’s bloodthirsty cold warriors, liberation theology was a synonym for communism. In El Salvador, “Haga patria, mate un cura” (“Be a patriot, kill a priest”) was a popular right-wing slogan. As the UCA emerged as a center of emancipatory thought and dissent to the dictatorship, it became a target for harassment by the military and the ultra-conservative Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) party that took power in the spring of 1989.

Certainly, in deeply religious countries like El Salvador and Nicaragua, many revolutionaries were formed by their experiences in Christian base communities, and some clergy did take up arms. But like Archbishop Romero, the UCA’s Jesuits were leading voices against violence. The priests were men of extraordinary dignity and courage, renowned intellectuals and public figures, respected in their fields and beloved in the communities they served.

Ignacio Ellacuría, born in Basque Country, was a philosopher and theologian. Dean of the UCA at the time of his assassination, he was an outspoken critic of the military regime and its US backers, and a constant advocate for peace and for the poor. Ignacio Martín-Barówas a Spanish theologian and social psychologist.

Head of the UCA’s psychology department and founding director of the UCA’s public opinion polling institute IUDOP, Martín-Baró was known for his Freirean emphasis on consciousness-raising and pioneered the field of “liberation psychology.”

Segundo Montes, also Spanish, led the UCA’s sociology department and directed the university’s Human Rights Institute (IDHUCA); he was also known for his work with refugee communities displaced by the war. Amando López, Spanish, had served as dean of the UCA in Managua, Nicaragua following the Sandinista revolution from 1979–1983. He was a professor of philosophy and theology at the time of his murder. Juan Ramón Moreno, Spanish, had years of experience throughout the region. He was serving as assistant director of the UCA’s Monseñor Romero Center.

Joaquín López y López was a Salvadoran who taught at the Externado San José, the prestigious San Salvador Jesuit high school, and founded the Fé y Alegría community arts and education extension program. Elba Ramos, also Salvadoran, worked as a cook and housekeeper for the Jesuits since 1985. She lived on campus with her husband, who was employed as a gardener. Their daughter Celina Mariceth Ramos, fifteen, was a high school student.

The Murders

The events took place during the FMLN’s November 1989 “final offensive,” which brought the war from remote mountain regions to the doorsteps of the wealthiest neighborhoods in San Salvador. But it was in the working-class communities surrounding the capital where the guerillas formed their bastions, and where the Salvadoran Air Force conducted a massive bombing campaign to drive them out. The dramatic show of force failed to overthrow the regime, but it confirmed the FMLN’s formidable military capabilities and resolve, setting the stage for the UN-brokered negotiations that would eventually end the conflict.

In the first days of the insurrection, the army took over radio transmissions nationwide, broadcasting state propaganda. In an unusual move, the military opened the phone lines to callers. Denunciations and death threats poured in against union leaders, NGO representatives, and clergy, with messages like, “Ellacuría is a guerrillero. They should cut his head off!” The vice president himself accused the priest of “poisoning the minds” of Salvadoran youth.

When the offensive began, the Atlacatl Battalion was in the midst of a training by US Special Forces at their western headquarters. One commando unit was dispatched to the military command center in San Salvador, located within blocks of the UCA. They arrived on November 13, and were immediately ordered to search the Jesuit residence on the university campus. The soldiers turned up nothing. They would return two days later with a far more sinister task.

On the evening of November 15, as the FMLN’s assault continued full force, the entirety of El Salvador’s military leadership gathered at the command center, accompanied by US advisers. President Alfredo Cristiani was also on hand, signing off on the areal bombings. The UN Truth Commission would subsequently conclude that General René Emilio Ponce, chief of staff of the Salvadoran Armed Forces, gave the order to assassinate Ellacuría that night — and to leave no witnesses.

In the early hours of November 16, dozens of soldiers with the Atlacatl Battalion entered the campus. They faked an attack, damaging parked cars and detonating a grenade. As some monitored the perimeter, others surrounded the Jesuit residence. After the soldiers began to force their way in, the priests opened the doors.

The soldiers lead the five Spaniards into the garden in their pajamas. They were ordered to lie down on the lawn. Elba and her daughter were held at gunpoint inside. The commanding officer gave the order, and all seven were executed in a hail of gunfire. Joaquín López y López, hidden indoors, was discovered, then shot.

Before withdrawing, the soldiers ransacked the nearby Monseñor Romero Center, scrawling “FMLN” on the walls and outside the campus gates. In the following weeks, the Salvadoran government would claim that the guerillas had committed the murders.

In a statement, the Cristiani administration declared that the crime was “intended to destabilize the democratic process and increase even more the climate of anguish created by the FMLN.” It wasn’t until January 1990 that, in the face of overwhelming evidence and international outcry, the Salvadoran state was forced to admit the military’s responsibility.

Thirty Years of Impunity

Justice for the material and intellectual authors of the massacre has been consistently distorted, deferred, and denied. From the legislature, the courts, and the military, the loyal servants of the right-wing extremists that continue to dominate the country’s capitalist class have sought every possible means to avoid a reckoning with this and other emblematic wartime atrocities. They have been aided by the US military and intelligence establishment, which colluded with the Salvadoran high command to shield top officials from investigation.

The massacre sparked an international firestorm. Cristiani, who found himself under immense pressure from US allies to restore faith in his faltering administration in order to justify ongoing military aid, eventually convened a military commission to investigate.

The commission promptly named nine men, all but one of whom were lower-ranking soldiers who directly participated in the murders. None belonged to the high command. Facing threats and obstruction from within the Cristiani administration and the Armed Forces, members of the state prosecution team resigned in protest.

The trial was a sham, conducted by a militarized regime at war with its own people. Despite multiple confessions, only two men were ultimately convicted on homicide charges: Colonel Guillermo Alfredo Benavides, the director of the Military Academy who communicated the orders to assassinate Ellacuría to the Atlacatl Battalion, and Lieutenant Yusshy Mendoza, who helped lead the unit that perpetrated the massacre.

A 1992 report from the International Commission of Jurists concluded that “justice was not achieved in this trial; indeed, justice probably could not have been achieved” in such conditions.

Both were sentenced to the maximum of thirty years. But in a matter of weeks, the legislature, dominated by Cristiani’s quasi-fascist ARENA party, forced through an amnesty law shielding perpetrators from prosecution for crimes committed during the war. The 1993 legislation amounted to a mass self-exoneration by the Right, disproportionately threatened by potential suits, and it would remain on the books until the Supreme Court’s reversal in 2016. The men served only a few months in prison before the amnesty law triggered their release.

For years, the UCA pursued the “intellectual authors” of the crime — those who planned and ordered the massacre — in Salvadoran courts, seeking not their imprisonment, but a process of truth, justice, and forgiveness. Nevertheless, the attorney general’s office refused to investigate, invoking the amnesty law.

A 1999 report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States found that El Salvador had violated the human rights to life, due process, and knowledge of the truth. The following year, a court ruled that the massacre was not covered by the amnesty law but rejected the UCA’s suit against the military high command, claiming that the statute of limitations had expired.

Finally, international solidarity reactivated the case. In 2008, the US-based Center forJustice and Accountability (CJA) and the Spanish Human Rights Association filed suit in Spain under the country’s doctrine of universal jurisdiction against Cristiani and nineteen former military members for their role in the massacre.

These included former defense minister general Rafael Humberto Larios; former Air Force chief general Juan Rafael Bustillo, also implicated in the infamous 1981 El Mozote massacre and known for running a joint US supply operation for the Nicaraguan Contras out of a Salvadoran air base; former vice minister of defense general Juan Orlando Zepeda; former Armed Forces chief of staff general René Emilio Ponce; Colonel Benavides; and the improbably named Colonel Inocente Montano, former vice minister of public security.

In 2011, at the request of the Spanish court, INTERPOL issued arrest warrants for eighteen Salvadoran former military officials implicated in the massacre. Nine of the perpetrators, including the former defense minister and vice minister, the former Air Force commander, and the lieutenant who led the massacre took refuge in a Salvadoran military barrack. The Salvadoran Supreme Court, however, rejected the warrants. Only Montano was arrested, in the United States, where he had been living for some ten years.

In 2015, El Salvador’s Supreme Court reversed its decision, allowing the arrests to go forward. In February 2016, the same day that US courts authorized Montano’s extradition to Spain, Salvadoran police detained four of the defendants, all lower-ranking soldiers, with the exception of Benavides. The court, however, again denied extradition. On the grounds that they had been acquitted in 1991, three of the defendants were released. Only Benavides was imprisoned. No longer protected by the amnesty law, he was ordered to complete his original thirty-year sentence.

Three decades later, the walls are closing in on those who conspired to kill Ellacuría and his cohort. Montano was extradited from the United States to Spain in 2017, where he faces up to 150 years in prison. Two of the lower-ranking officers, Lt Mendoza and Lt Colonel Camilo Hernández, opted to collaborate with the Spanish prosecution. The rest, fugitives from international law, remain protected by the Salvadoran Supreme Court from extradition. But their long-standing immunity in the Salvadoran judicial system may at last be wearing thin: in 2018, the UCA’s case against the military high command was finally reopened by a Salvadoran court.

The halting, circuitous march toward justice for the Jesuits advances as the trial for earlier victims of the Atlacatl battalion moves forward in El Salvador. In 2016, a Salvadoran court ordered the reopening of the case against seventeen high-ranking former military officials for the 1981 massacre at El Mozote, which left nearly one thousand civilians dead, half of them children. Exhumations at the site of the massacre are ongoing. A generation of cold warriors who seemed to have escaped justice now finds itself in the crosshairs.

How Many Thousands?

In El Salvador, the United States joined forces with some of the most brutal reactionaries in the region to repress popular movements for equality, justice, and self-determination. US financing, weapons, strategy, and political support sustained the scorched-earth counterinsurgency campaign for years. US intervention helped ensure that it was Cristiani’s ARENA party that dominated the postwar transition, implementing sweeping neoliberal structural adjustment and free trade policies that favored US capital at the expense of millions of Salvadoran workers who, displaced and dispossessed in peacetime, were forced to migrate north.

But just as US imperialism made these horrors possible, international solidarity has been key in the struggles for justice. US advocates have secured broad caches of declassified army and intelligence documents from the war period. The Spanish suit was aided by a trove of materials obtained by the National Security Archive confirming key details of the case as well as the US role in obstructing the search for the truth.

The University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights was the victim of a break-in and theft of a computer and hard drive after it filed suit against the CIA for records pertaining to the war and the role of high-ranking Salvadoran officials in the Mozote massacre.

The veteran US solidarity organization School of the Americas Watch was formed in response to the Jesuit massacre and hosts an annual vigil at the gates of Fort Benning to denounce the US role in crimes across the hemisphere. The group estimates that over eighty-three thousand Latin American state security forces have been trained at the site, which now bears the deceptively benign title of Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC).

These graduates have carried out coups, massacres, assassinations, torture, disappearances, economic destabilization, and mass displacement. Recently, ICE revealed that agents will train in domestic “urban warfare” at Fort Benning, bringing SOA’s counterinsurgency project full circle.

In a 1983 text called “The Truth About American Intervention in El Salvador,” Ellacuría wrote: “History shows that Yankee intervention, far from favoring the peoples of Latin America, far from promoting their democratic self-determination, has put them in the position that so many find themselves in today, by favoring genocidal antidemocratic regimes (Somoza, Argentine and Uruguayan military officials, Stroessner, Pinochet, among others) and by allying with oligarchic sectors that have maintained the underdevelopment and exploitation of the vast Latin American majorities.”

Facing the Reagan administration’s determination to escalate the war, Ellacuría wondered, “How many thousands will have to flee their homelands or simply be displaced from their homes and workplaces, which American weapons have now turned into places of death and destruction?”

The priest’s words remind us that the UCA martyrs take their place among millions of victims of the US-backed wars on communism, on drugs, and on terror worldwide. Even as the struggle for truth and reparations in El Salvador moves forward, the US imperial machine continues to churn out death, displacement, and authoritarianism. The top military officials involved in the unfolding coup against leftist indigenous President Evo Morales in Bolivia are graduates of the SOA and Washington police training programs.

Many of the Jesuits abandoned the safety of their homeland to serve in solidarity with the exploited and oppressed in Central America. They offered their lives in pursuit of peace and a more equitable world, free from the dictates of oligarchs, generals, and imperial overseers. As long as the monstrous military-industrial complex — its surveillance networks, military bases, international training programs, and weapons markets — casts its shadow across the globe, true justice for the casualties of US foreign policy in El Salvador and beyond will remain incomplete.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.