Hundreds protest FBI raids on antiwar activists.

Court Orders FBI to Expunge Website Records under Privacy Act

Lyndsey Wajert / Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press

WASHINGTON (January 16, 2020) — In late November, a judge for the US District Court for the Northern District of California directed the Federal Bureau of Investigation to expunge certain records relating to Eric Garris, an editor of the website Antiwar.com, which describes itself as promoting “non-interventionism” and posts related news and opinions.

The move comes after the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held in September that federal law prohibits law enforcement agencies from maintaining records describing First Amendment activity, unless the record “is pertinent to and within the scope of an ongoing law enforcement activity.” The case marked the first time the Ninth Circuit has considered that question.

Garris v. FBI involved the FBI’s collection and maintenance of records on the editors of Antiwar.com. The site’s editors and co-founders, Garris and Justin Raimondo, challenged the bureau’s preservation of records describing their work and sought to have the records expunged under the Privacy Act of 1974.

The court of appeals agreed with their arguments related to a detailed post-9/11 “threat assessment” memorandum, noting that the FBI did not demonstrate that the memo at issue was “pertinent” to ongoing law enforcement activity.

Regarding the 2004 FBI memo, the court stated: “It cannot be that maintaining a record of purely protected First Amendment activity is relevant to an authorized law enforcement activity simply on the representation that maintaining the record would ‘serve to inform ongoing and future investigative activity.’”

This decision may be significant in light of recent high-profile examples of government efforts to monitor journalists based on newsgathering activity. In May, for instance, the Reporters Committee joined a group of 103 organizations that signed a letter to the then-acting secretary of the US Department of Homeland Security raising concerns over reports of surveillance activities by US Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The letter called for an end to the practice, warning that surveillance of journalists may violate the Privacy Act and infringe on the rights of the press.

The court’s decision to clarify what is permissible under the Privacy Act is also notable given the history of the law.

History of the Privacy Act

Congress passed the Privacy Act of 1974 largely to address instances of illegal government surveillance of individuals based on what many considered to be protected First Amendment activity. As our Reporters Committee colleague Linda Moon noted in June, “Revelations of domestic surveillance of journalists and others exercising First Amendment rights were in the minds of lawmakers considering the Privacy Act prior to its passage.”

Indeed, from about 1956 to 1971, the FBI targeted political organizations it deemed “subversive” through an operation called “COINTELPRO.” The bureau gathered intelligence through illegal surveillance methods, and agents were instructed to discredit the leaders of the groups. Both the CIA and NSA also had programs monitoring, among others, journalists.

In 1974, Congress responded to these programs by passing the Privacy Act, along with amendments to the Freedom of Information Act. The Reporters Committee observed in 2009 that, “Together, the laws were meant to keep the public aware of government’s machinations, while giving meaning to a person’s right to be free from government intrusion.”

The Privacy Act permits individuals to access and correct records on them held by the government. Crucially, it mandates that the government “maintain no record describing how any individual exercises rights guaranteed by the First Amendment unless … pertinent to and within the scope of an authorized law enforcement activity.”

The question in Garris was whether the FBI could legally hold on to memos on First Amendment activities that were no longer pertinent to an ongoing case.

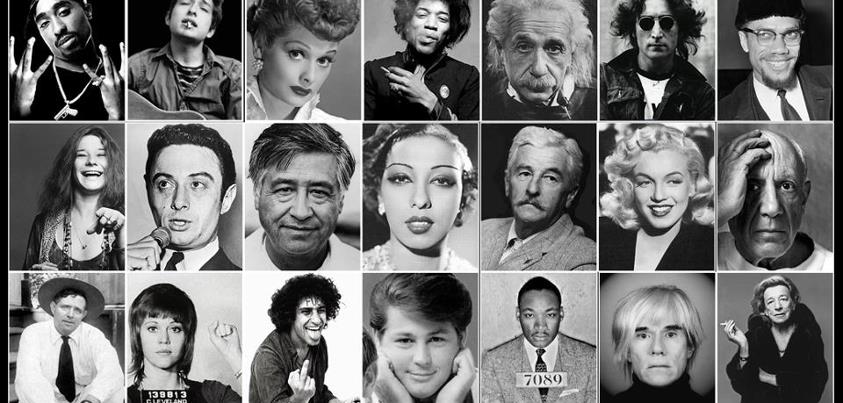

Not-so-well-known: Some of the many ell-known Americans targeted by the FBI.

The Ninth Circuit’s Decision

While the website Antiwar.com self-describes as advocating for “non-interventionism” — effectively opposition to interference in other nations’ affairs and war except in self-defense — the content on the site includes both original and aggregated news and analysis on war, foreign policy, civil liberties, and other related issues.

After learning through documents released pursuant to Freedom of Information Act requests that the FBI had created records focusing on their website, Garris and Raimondo filed the action in 2013. Raimondo passed away last year, but Garris’ appeal remained.

The issues for Antiwar originated almost two decades ago. According to Brennan Center for Justice fellow Mike German’s book “Disrupt, Discredit, and Divide,” on Sept. 12, 2001, Garris received an email threatening to hack the website. He forwarded it the FBI, but did not receive a response.

In March 2004, the FBI informed all field offices that an unclassified post-9/11 suspect list had been posted on the internet. “An FBI agent subsequently discovered a twenty-two-page untitled Excel spreadsheet, dated 10/03/2001” — likely an FBI watchlist — published on Antiwar.com.

The Newark, New Jersey, office of the FBI prepared a 10-page “threat assessment” on Antiwar. The memo described the site’s mission and included a description of six articles found through a Lexis Nexis search for Garris and Antiwar.com. Further, the memo noted that “persons of interest” to the FBI had accessed or discussed the website.

The memo ultimately indicated that the Newark office recommended that the FBI’s field office in San Francisco monitor Garris and Antiwar’s postings. Yet the San Francisco office declined to do so, explaining that the website was “not a clear threat to National Security.” It categorized the site as a source of public information and said Garris “[was] exercising [his] constitutional right to free speech.”

Garris learned of the 2004 memo after it was released as part of an unrelated FOIA request. Garris then filed his own FOIA request, and the subsequent response was not as heavily redacted as the version that was posted online. The document stated that Garris had threatened to “disrupt FBI operations by hacking the FBI website.”

As German points out, however, this was clearly a mistake. The analyst who received the email from Garris believed the message was a threat against the FBI, and did not realize that Garris was actually forwarding the email that contained the threat against Antiwar’s own website. Still, according to the memo, the FBI continued to monitor Garris and Antiwar.

Garris filed FOIA and Privacy Act requests seeking all FBI records about him, and when he exhausted the administrative remedies, he filed a lawsuit. He also separately filed requests seeking expungement of all records maintained by the FBI that described his exercise of First Amendment rights.

During the litigation, Garris also learned of the existence of another memo, called the “Halliburton Memo.” In 2006, the FBI’s Oklahoma City field office created the memo, which detailed plans by groups to protest Halliburton, the oil field services company once run by former Vice President Dick Cheney. Antiwar.com had posted information about a Halliburton shareholders’ meeting, and so the website was listed in the memo as one of the sources of publicly shared information about the meeting.

Garris sought expungement of these records, arguing that the law enforcement activity exception did not apply to them because the investigations in both memos had ended and the records were not pertinent to an ongoing authorized law enforcement activity.

The US District Court for the Northern District of California ultimately granted summary judgment to the FBI. The parties settled the remaining disclosure issues, but Garris appealed the Privacy Act claims.

Though there were many issues for the court to consider, the most pertinent for press freedom purposes was whether maintaining the 2004 memo and the Halliburton memo violated the Privacy Act, or whether they fell within the “law enforcement activity” exception (i.e., the government can maintain records if “pertinent” to an authorized law enforcement activity).

The question largely turned on statutory interpretation. The FBI argued that the “law enforcement activity” exception allows agencies to both collect and maintain records so long as they were pertinent to an authorized law enforcement activity at the time of collection. But the appeals court rejected that interpretation, stating, “to accept the FBI’s preferred reading would be to read the word ‘maintain’ out of the statute.”

The court suggested that if that had been the intent, Congress could have specifically stated that it was enough to fall under the exception for a record to be “compiled for” an authorized law enforcement activity. Instead, the court reasoned that, according to the language, each act of an agency must individually be justified to fall under the exception.

The decision also highlighted the legislative history of the Privacy Act. Quoting MacPherson v. Internal Revenue Service, the appeals court ruling stated that “Congress was clearly interested in preventing both collection and retention of records, with a strong eye to preventing the government from maintaining ‘information not immediately needed, about law-abiding Americans, on the off-chance that Government or the particular agency might possibly have to deal with them in the future.’”

Yet the government had contended just that, saying the maintenance of the 2004 memo would “serve to inform ongoing and future investigative activity.”

The court ultimately held that this was not enough, and the FBI had not met the burden under the interpretation of the Privacy Act. Instead, “The 2004 Memo specifically details Garris’ protected First Amendment activities, including his political views and articles he wrote, allegedly to conduct a threat assessment prompted by the posting of the FBI watch list.”

The court even noted that the FBI conceded that the posting of the list was protected First Amendment activity. The FBI failed to offer a connection between the memo and a specific investigation, and so the “law enforcement activity” exception did not apply.

This acknowledgement — by both the FBI and the court — is important. Indeed, as the Reporters Committee has previously noted, news outlets are often the recipients of leaked or classified information. It is common for many news outlets to post full or edited versions of documents. Yet posting information that has been obtained legally is not illegal. Indeed, the act of posting government information should not in itself warrant opening an investigation into the outlet or its reporters.

While the court did note that the Halliburton memo was of “ongoing relevance” to law enforcement’s preparation for “an oft-protested meeting,” the court also stated the Halliburton memo was not specifically filed under Garris’ name or that of Antiwar.com. Instead, the website was listed merely to provide context as to where coverage of the shareholders’ meeting can be found.” Thus, the court stated that the memo did not have to be expunged.

Ultimately, given the court’s holding on the 2004 memo, this decision sheds light on an important but rarely considered provision of the Privacy Act, and clarifies in the Ninth Circuit that government agencies have an obligation to expunge records that lack a direct connection to an ongoing criminal investigation.

The Reporters Committee regularly files friend-of-the-court briefs and its attorneys represent journalists and news organizations pro bono in court cases that involve First Amendment freedoms, the newsgathering rights of journalists and access to public information. Stay up-to-date on our work by signing up for our monthly newsletter and following us on Twitter or Instagram

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.