‘Cult Of Glory’ Reveals The Dark History of The Texas Rangers

(June 8, 2020) — TRANSCRIPT: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Dave Davies in for Terry Gross.

The events of the past 10 days are a painful reminder that police officers we count on to serve and protect our communities can sometimes abuse their authority and commit brutal acts whose victims are disproportionately people of color. Our guest today, journalist Doug Swanson, has a new book about one of the oldest and most celebrated law enforcement agencies in America, the Texas Rangers.

The heroism and exploits of the Rangers have been portrayed for decades in Broadway plays, dime-store novels, radio dramas and movies and TV shows, most notably “The Lone Ranger.” But in the five years he spent researching the Rangers, Swanson also found a dark side to their story.

They burned villages and slaughtered innocents. They committed war crimes, hunted runaway slaves and murdered so many Mexicans and Mexican Americans that they were as feared on the Mexican border as the Ku Klux Klan was in the Deep South.

Throughout it all, Swanson writes, the Rangers operated a fable factory to burnish their image as heroic defenders of the innocent.

Doug Swanson is a veteran reporter and editor who spent much of his career at The Dallas Morning News. He’s written five novels and a previous book of nonfiction. He’s now a research assistant professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh.

His new book is “Cult Of Glory: The Bold And Brutal History Of The Texas Rangers.” I spoke to him from my home in Philadelphia. He was at his home in Pittsburgh.

Well, Doug Swanson, welcome to FRESH AIR. This book is full of colorful characters and great stories, some about some admirable crime-fighting. But you also spent a lot of time looking at examples of abuse of police authority, I mean, some of them real atrocities. And, you know, you had to sort out conflicting versions of events, get at hidden truths. You were immersed in this issue for some time, and I’m wondering what your reaction was to the death of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police and the days of protests that followed. Did this have an extra resonance for you?

DOUG SWANSON: Oh, sure. And like many people, I thought this is an old, old story in so many terrible ways. I mean, some of the worst of this happened with the Rangers a little over a hundred years ago along the Texas-Mexico border. You know, they didn’t invent police brutality, but they perfected it down there on the border, where they operated as what we would now term death squads. And as you noted in the intro, they executed hundreds, perhaps thousands of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. And some of those were bandits who had attacked white-owned farms and ranches, but many of them had committed no crimes. You know, they were guilty of having brown skin.

DAVIES: And as you kind of watch these events, had you developed thoughts about how this culture can change?

SWANSON: Well, I think it has to change in so many ways, as so many people have pointed out. But I think in terms of history, it’s important to take a look at all the old stories, as I’ve done here, and pick apart the legends and look at different points of view, find different voices here and talk about what really happened, help us understand what’s really behind all of this. If we start to understand it, I think we can start to deal with it.

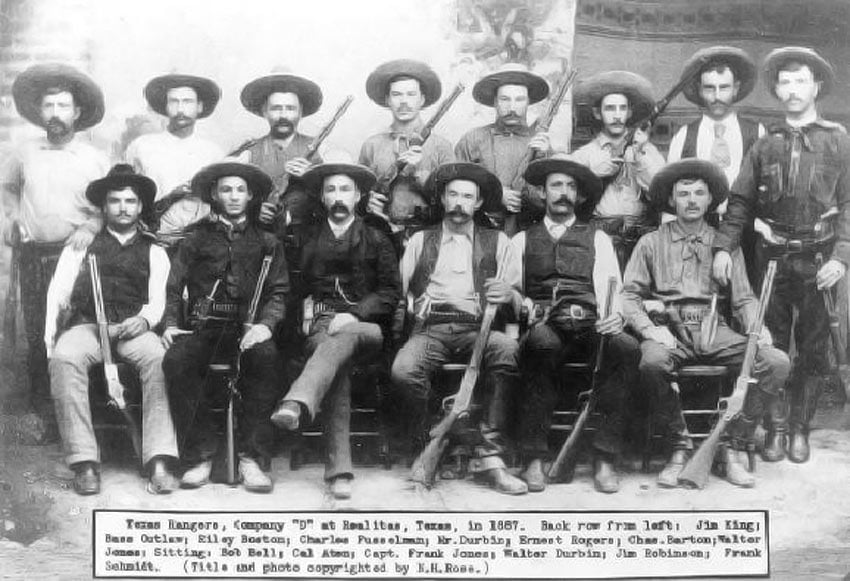

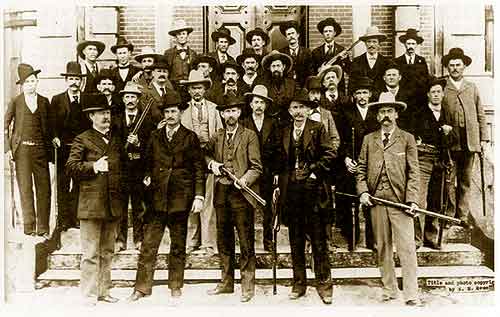

DAVIES: OK, so let’s talk about the Rangers. They go all the way back to 1823, when Anglo settlers first moved into what would later become Texas. And the early Rangers were not exactly the crisply uniformed force they would eventually become. You want to describe these guys, the early Rangers?

SWANSON: Yeah. They were a ragtag bunch. About 10 of them had been put together mainly to deal with the Karankawa Indians, who were a coastal tribe in Texas. They were very big Native Americans — large physically — and they were trying to protect their land. There was what they saw as interlopers. And the Texas settlers who came from places like Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri — they wanted the Karankawa out of there. And Steven F. Austin — you know, the father of modern Texas — declared that the Karankawa needed to be exterminated. So that was really the proto-Rangers — that was their first mission to protect against the Karankawas and then finally to eliminate them, which they did.

DAVIES: You say they were a ragtag bunch — no uniforms — right? — tough guys.

SWANSON: Well, they were farmers. They were teachers. They were cowmen. They were, you know, a bunch of working stiffs who signed up to try to protect the settlement. They didn’t last very long. They ran out of ammunition and food, so they went back to their regular jobs. You know, the beginning of the Rangers was — it was very murky and irregular and sort of struggled along for a number of years until 1835, when the provisional government of the Republic of Texas formally established the Texas Rangers.

DAVIES: So Texas wins its independence from Mexico in 1836 — you know, the military campaign that included the Alamo. And you write that the Anglo country was rich in enemies, these ranchers and farmers in Texas. There were Mexicans to the south, Indians throughout. So what role did the Rangers play in the decades that followed?

SWANSON: Well, they were very skilled executioners on the behalf of the white power structure. They did fight Mexicans who might come across the border. They sometimes went across the border themselves to get cattle and other things. And they fought the Indians. They wiped the Cherokees out. They wiped out some other tribes. And then they had to fight the Comanches, who were much more difficult battle.

DAVIES: Now, in the late 1840s, after Texas had joined the Union, the United States, the US fought a war with Mexico that would lead to a huge expansion of US boundaries at Mexico’s expense. And a lot of the fighting was in Texas in areas near Mexico. What was the role of the Rangers in that conflict?

SWANSON: The Rangers were really valuable to the US Army. And they weren’t technically Rangers at that point because they had joined the United States forces, but they still operated as Rangers. They stayed together. They didn’t wear uniforms. They wore the old Ranger clothing that they always wore — wide-brimmed hats and their greasy pants. And they’re carrying their guns on the gun belts. But their role often was as scouts, advanced troops, guerrilla forces because they knew what it was like to fight in the desert Southwest. They knew the turf. And they were extraordinarily tough. So they played a very valuable role for the United States forces during the Mexican War.

At the same time, the Rangers were motivated by their hatred of Mexicans. They blamed the Mexicans for any number of atrocities, including the Alamo, and they were out for revenge. So they quickly established a reputation as the Los Diablo Tejanos, the Texas devils. They executed any number of innocent people. They would move into small villages and shoot every man in the village, innocent or not. They were extremely feared by the Mexicans during the Mexican War.

DAVIES: Did they loot places? Did they get bounty from this? Was there — were they enriched by this fighting at all?

SWANSON: Oh, sure. I mean, that was part of the spoils of war. There’s no doubt about that. They looted. They killed. You can find accusations that they raped, all of that. At the same time, as I said, they were really valuable components of the US war effort.

DAVIES: There was a particularly notorious incident in not the Rio Grande Valley — a little bit farther west in West Texas at a little village called Porvenir. Tell us what happened there.

SWANSON: Yeah, that was out in what’s called the Big Bend out near El Paso — a little tiny village, as you say, Porvenir, full of very modest goat ranchers and farmers. They lived in basically shacks. And one night in January of 1918, the Rangers — about maybe half a dozen of them — and some US cavalryman rode out to Porvenir supposedly to investigate a raid on a ranch. And it was the middle of the night, very dark out there, you know, just the middle of nowhere on the Mexican border. The Rangers pull up with the cavalry, and they took 15 boys and old men out of their little shacks and took them away from the village, put them up against a wall and executed all of them, then rode away and then tried to cover it up.

Fortunately, there was an Anglo schoolteacher who lived out there who was so familiar with all these people and went out the next day and found out what had happened and tried to report it to the authorities, was not taken seriously at first but kept at it. And the Rangers were eventually exposed. And those who were in this party were dismissed from the Rangers. No one was ever prosecuted, but there were 15 men, old men and young boys as young as 15, who were executed that night for no reason.

DAVIES: What happened to the surviving women and children in the village after all the men were taken out and executed?

SWANSON: Oh, they fled in terror across the river into Mexico. They eventually got some small financial settlements, but the village was burned to the ground by the army afterwards. And that was that. You know, that’s the way it worked in that time and that place with the Rangers.

DAVIES: And this incident actually came to light and became an international controversy, right? How did that happen?

SWANSON: Well, the Mexican government pressed the issue and wouldn’t let go. For once, you know, the United States had to listen to the Mexicans. And they kept it on the burner, and it became an issue in the Texas gubernatorial campaign. And that’s why the Rangers were let go, so the governor could be reelected.

DAVIES: So there was an investigation. There was discipline but no charges against any of the Rangers.

SWANSON: That’s correct. It was very rare for any Ranger to be charged with killing a Mexican. That just didn’t happen.

DAVIES: Not to say that there — I’m sure there were heroic acts by some Rangers and some good crime fighting at times, right?

SWANSON: Oh, of course. There’s no doubt about that. This was not a force that was completely full of criminals and miscreants and, you know, people who didn’t fit. There were some great Rangers. We can’t lose sight of that. But that’s not the whole story by far.

DAVIES: Let’s move into the — a little farther into the 20th century. In the 1930s, the Rangers were sort of reorganized, I gather, due to some sort of problems or scandals. What happened?

SWANSON: Well, Texas got a new governor, Ma Ferguson, in the 1930s, and she fired all the regular Rangers and installed her cronies and her hacks. And it became an agency of political favoritism — very ineffectual, very corrupt at that point. So once Ferguson was out of office, a reform movement came in, and the Rangers were reorganized in the mid-1930s under what was then and is now called the Department of Public Safety with an eye toward making them more professional, better trained and a more rigorous law enforcement organization. That took some time, but that was the goal.

DAVIES: Yeah. What were some of the high jinks that the Rangers were up to under Ma Ferguson?

SWANSON: Well, you know, they were after — they were cracking down on gambling. And the reason they were cracking down on some of the gambling casinos was so they could establish their own casinos. There was a very notorious Ranger who would come in and force casino owners out and then take over their casinos himself. That was going on a lot. They would stop motorists and demand payoffs to not arrest them — just a general level of graft and corruption that permeated the agency at that point.

DAVIES: Right. And so after the reform, were the Rangers more professional?

SWANSON: To a point. I mean, it was gradual, like everything else. But, yeah, there were movements toward better training, better screening of Rangers, taking them out of the direct control of the government and putting them under a commission, which supposedly led to less political interference. That didn’t happen right away, but that, again, was the goal. But, yeah, there was a slow, gradual movement toward the professional law enforcement force that we have today.

DAVIES: In the 1950s, after the US Supreme Court ruling, you know, Brown vs. Board of Education ordered the desegregation of public schools, there were efforts in Texas particularly pushed by the NAACP, and you write about one high school in Mansfield, Texas — this is in east Texas — and then another involving Texarkana Junior College. And the Rangers became involved because this was going to be controversial. And a key Ranger in these incidents was a guy Sergeant Jay Banks. Before we talk about the incidents themselves, just tell us a little bit about Banks, what kind of profile he struck.

SWANSON: Banks was a small-town guy, grew up on a farm and was a law enforcement lifer, had a pretty good career as a Ranger, and he looked like a Ranger. That’s what many people liked about him. He was big and handsome. He was on the “Today” show once in his Ranger gear. He just — you know, you looked at Jay Banks and you thought, hey, that’s a Texas Ranger right there.

DAVIES: Right. And so what happened when he was sent to these two incidents in Mansfield, Texas, and in Texarkana to deal with an attempt to integrate public educational institutions?

SWANSON: The NAACP wanted to make its first test case Mansfield High School, which was actually between Dallas and Fort Worth. It’s now a suburb. But back then, it was a pretty small town. And the governor of Texas at the time, Allan Shivers, was very much against integration. He thought it was against God’s law.

So he sent the Rangers and the person of Banks, who was in charge, and a few others with instructions to arrest any black student who tried to enroll in Mansfield High School. There were mobs out front carrying racist signs and threatening to kill any student who enrolled. And Banks found himself sympathetic with them. As he later said, they were just salt of the earth people who were challenged because their way of life was under assault.

So he stood virtually in the schoolhouse door in Mansfield and prohibited any black student from enrolling. Same thing happened about a week later at a community college in Texarkana, Texas. He stood with the mob and threatened to arrest any students who showed up. A boy and — a young man and a young woman showed up and tried to enroll. And the mob blocked their path. Banks again threatened to arrest them. And they left. So he’s successful. He was following orders. Let’s make that clear. He was following the governor’s orders. But he successfully in these two cases thwarted any integration efforts in Texas public schools.

DAVIES: There’s a striking photo in the book of him in Mansfield. You want to describe this?

SWANSON: Yeah. He’s leaning up against a tree out in front of the Mansfield High School. And behind him, hanging above the entrance of the school, is a black figure hanging in effigy. And banks and the other Rangers refused to take it down because they said they didn’t put it up. You’re right. It is a very striking photo. And, you know, given what’s going on today, it really has some resonance. And we’re going back again to 1957. That’s a long way back. But it still echoes today.

DAVIES: How did Sgt. Banks treat others on the scene in advance, like journalists, for example? I mean, this was this was a noteworthy event.

SWANSON: If reporters came around and started asking uncomfortable questions, Banks removed them, sometimes, as he said, with the aid of a Ranger’s boot. Or he would threaten them with arrest or he would tell them he was going to take their cameras and expose their film. He was not friendly to two journalists who were working. At one point, a priest showed up and tried to talk to the crowd about loving one’s neighbor. And Banks escorted him from the scene. He didn’t have to kick him but he did escort him from the scene.

I mean, Banks wasn’t putting up with any nonsense at these places. He became good friends with the White Citizens’ Council, which is a pro-segregationist group all across the South. But they had a branch in Texarkana. And when it was all done, the White Citizens’ Council was so happy with Ranger Banks, they gave him a chicken dinner.

DAVIES: You know, it’s not so remarkable for local law enforcement to support segregationists in the South in the 1950s. It is kind of remarkable how Sgt. Banks’ actions as a Ranger were remembered and described in later media accounts. Tell us about that.

SWANSON: Oh, he was presented as a hero and was…

DAVIES: For this stuff.

SWANSON: For these actions. Yes, it was again and again, he was described in media reports as the man who kept the mobs under control and kept the scene pacified and helped bring peace to a volatile situation. Well the way he did that was, as I said, threaten to arrest any black student who showed up and tried to enroll.

DAVIES: There’s an interesting postscript to this that is very, very recent. This involves a statue of Sgt. Banks, which has stood for many years in Love Field, which is one of two airports in Dallas. What’s — tell us about this.

SWANSON: The statue was sculpted in the late 1950s — 1959 — somewhere in there. A local businessman, a man who ran a chain of cafeterias, wanted to have a statue commemorating the Rangers. And as I said, Jay Banks was a very handsome guy. He looked like a Ranger. And so the sculptor used him as the model. It stands about 12 feet high on its base. Lovely brass statue. And for many, many, many years, it has stood in the lobby of Love Field. And for passengers disembarking and coming down the steps into the main lobby, that’s what the first thing they see is — is this big statue of Jay Banks.

Now that the book is out, the city of Dallas has decided that this statue is going to be removed. And I think they are removing it as we speak. And what happens to it? I don’t know. Where it goes I don’t know. But the discussion has started.

DAVIES: As the nation deals with the fallout of a horrific police killing in Minneapolis, we’re talking to veteran investigative reporter Doug Swanson. He’s written a book about a law enforcement agency widely celebrated in TV and film, which, he discovers, has a little-known history of abusive conduct and racial and ethnic oppression. His history of the Texas Rangers is called “Cult Of Glory.”

The Rangers had quite a history with the Texas NAACP, didn’t they?

SWANSON: Yes, they did. In fact, back in 1919, which is, you know, known as the Red Summer across the country for all the lynchings and racial incidents — there was one in the Longview, Texas, in east Texas — nearly collapsed in a race war. So the Rangers decided they had to do something about that. They were very concerned about racial outbreaks in Texas. But what they decided to do was force the NAACP out of Texas.

So again, on the governor’s orders, they began meeting with police chiefs and sheriffs across the state, trying to figure out ways to infiltrate NAACP meetings, to stop black-oriented newspapers from coming into Texas. They would talk to the postmasters, you know? If you see any of these papers like The Chicago Defender and others, tear them up. Don’t deliver them. They talked to gun stores and told them, don’t sell any guns, legally, to black people. And then they tried to break up the meetings, where, as they warned, black people were trying to figure out ways to get their rights. That was a bad thing back in 1919 in Texas as far as the Rangers were concerned.

DAVIES: What was the impact on the NAACP?

SWANSON: Well, eventually, they were forced out of the state. This happened after the desegregation efforts of the 1950s. The state, itself — the attorney general and other powerful members of the state — took the NAACP to court and had them, for a while, thrown out of Texas. They were seen as an illegal operation in the state of Texas. The Rangers, again, were part of that, but just a small part.

But this goes back to the general theme, which is, yes, there were heroic Rangers. Yes, they’d done many good things. But they have acted, throughout their history, as the force of the white power structure and the state. That’s been their role and large part.

DAVIES: I want to talk about the Rangers’ role in a farmworker’s strike in the Rio Grande Valley in the 1960s. But before we get to that, just tell me just a little bit about the Rangers’ history of dealing with labor disputes.

SWANSON: Well, the Rangers have been, as I said, the agents of the government. So if the government thought a strike needed to be broken, they often sent in the Rangers. They broke up railroad strikes. They broke up longshoremen strikes. They even broke up a cowboy strike up in the panhandle a long time ago. So they had a long history as strike-breakers even before they got to the farmworkers down in south Texas in 1967.

DAVIES: Well, I want to talk about this farmworker’s strike in the Rio Grande Valley. A key figure for the Rangers was a captain named A. Y. Allee. And before we talk about what happened in the strike, just give us a thumbnail description of him and his style.

SWANSON: Captain Allee was a beloved captain by his men. He would always go first whenever there was a shootout. They loved him. But he was also, perhaps, the toughest Ranger of that era. And I think the proof of that was when a highway patrolman wrote Allee’s wife a traffic ticket. And Allee confronted the highway patrolman. And the highway patrolman somehow hinted that Allee’s wife might be lying. So Allee took out his pistol and pistol-whipped the highway patrolman. That’s what Rangers could do back in the 1960s in Texas. You didn’t mess with Captain A. Y. Allee.

DAVIES: All right. So let’s talk about this farmworker’s strike. Describe the circumstances of farm labor in the valley at the time.

SWANSON:These were Mexicans, Mexican Americans, who came across — who lived in the valley, the Rio Grande Valley of Texas in very primitive conditions. They lived in shacks. They lived in tents. When they were out in the fields — and south Texas is really hot during harvest season — they did not have drinking water. They did not have sanitation facilities. Some of the children described — when they were thirsty and they were out picking crops, they would have to drink water from the puddles in the ground.

So they allied with the farmworkers who came in from California, some of Cesar Chavez’s crew, and decided they were going to strike in 1967 in Starr County, Texas, and not harvest the melon crop. At that point, the county officials and the farm owners brought in the Rangers and the person of — Captain Allee and his company to break the strike.

DAVIES: There were some particularly noteworthy events, including a raid on a farmworker — a union organizer at his home. Tell us about that.

SWANSON: Yeah. His name was Dimas. And he was — he had a criminal history, there’s no doubt about that. But the Rangers didn’t like him. Allee didn’t like him. So they showed up at the house where Dimas was staying one night, drew their guns, slapped a few people around, raided the house, hit Dimas in the head so hard with the butt of a shotgun that he was sent to the hospital for stitches and had a concussion — and generally did what the Rangers did at that point, which was, if they didn’t like someone, they, you know, brought some persuasive violence.

DAVIES: There was also an incident involving a reverend and his wife.

SWANSON: Yeah, Reverend Ed Krueger, who was a representative of Texas Council of Churches, and his wife. They were down there marching with the farmworkers. And Allee and the Rangers intercepted them one day right next to some freight train tracks. And Krueger said that one of the Rangers grabbed him and held him up so close to the passing train that he thought he was going to shove his face into it. Krueger was very afraid for his life. But again, that’s what the Rangers did. They were an intimidating force when it came to these sorts of strikes.

DAVIES: Right. And by the 1960s, you know, Rangers couldn’t do whatever they wanted, you know, in anonymity. I mean, this got attention. It got — there was media attention. There was litigation. What happened?

SWANSON: Well, ultimately, they were criticized by the federal courts, a ruling that was upheld by the Supreme Court. There were various civil rights commissions actions that were very critical of the Rangers. And as a result, the Department of Public Safety decided they generally weren’t going to send the Rangers in anymore to break strikes. That was not a good use of the Rangers’ abilities and personnel.

And it gave the Rangers a tremendous black eye. So that changed. What also happened was, as a result of the strike, the Chicano Movement took flight in Texas and gained some political power. So the Rangers had an unintended effect here. By seeking to squelch Mexican Americans and their political action, they actually strengthened it.

DAVIES: Yeah. It really got some national media attention, didn’t it?

SWANSON: Yeah, it did, I mean, in part because of the Rangers’ actions, but in part because Allee was just such an unforgettable character. I mean, he was this muscular, doughy guy. One writer said he had a face like a sunburned potato. And he was always chomping on a cigar. And he would say things like, you know, these damn civil rights, that’s the damnedest thing I ever heard of. And he was just a quote machine as far as that goes. So I mean, what reporter could resist that?

DAVIES: Right. There’s a little postscript to this. After Captain Allee retired, you describe an encounter he had in a grocery store.

SWANSON: Well, Allee was notorious for slapping people. I mean, that’s the way he kept his — some of his opponents under control. He would — if a lawyer would confront him in court, Allee would wait for him outside the courthouse and slap him. I mean, that happened all the time, he just — you know, upside the head with an open hand. That was his technique. So Allee retired. And the Rangers praised him mightily when he retired as one of the greatest captains ever, one of the greatest law enforcement officers ever — that sort of thing.

He retires. He’s back in south Texas, where he grew up. And one year after his retirement, he walked into a grocery store in Carrizo Springs, his hometown, to buy a five-gallon jug of water. The clerk was a young, Hispanic man. He rang up a tab of $1.75. And Allee believed the actual price to be $1.35. So you know, rather than be cheated out of 40 cents — Allee was then 66 — pulls his gun and slapped the clerk — same old tactics.

DAVIES: So let’s talk a little bit about Rangers in the modern era. When was the force first integrated? It was all white for most of its existence.

SWANSON:Yeah, it was. Now, in the old days, we have to be clear — and by the old days I mean going back into the 1870s, around there — there were some Hispanic, Latino Rangers — a few, not many, but there were some. But if we’re talking the modern era, the first Hispanic or Latino ranger was hired in 1969. The first African American ranger came onboard in 1988, but that was only after an NAACP complaint. The first two women were hired in 1993. And now the agency has about 160 Rangers — four are women, eight are African American and 34 are Hispanic.

DAVIES: So it’s a pretty small force these days. Describe its role in Texas law enforcement.

SWANSON: It’s — it has several roles, one is to investigate official corruption. If a politician or government official is accused of corruption, the Rangers are brought in. They investigate jail deaths and police shootings. But, perhaps, their biggest role related to their tradition is they help small-town police departments and sheriffs’ offices and other law enforcement agencies, of which there are still a lot in Texas.

You know, if you’re a small-town department, you may not have any homicide detectives. And if you have a murder, you can bring the Rangers in to help. Or if you have a string of crimes or a criminal disturbance — something like that — the Rangers are there to assist if you ask them to come in. So they do that. They also have some intelligence operations going on on the border. They’ve been very secretive about that. But they are down on the border still, and in a big way.

DAVIES: A lot of them wear suits nowadays. But there is a dress code, right?

SWANSON: There is. You have to have a Western hat. You have to wear Western boots. You have to have a Western belt. You have to look very Western. But you’ve got to be crisp. It’s not like the old days in the Mexican War, where you could walk around with grease-stained pants and a torn shirt. You have to look very crisp and professional these days.

DAVIES: One of the roles of the Rangers nowadays is to look into police misconduct, things like shootings. What’s their record on that?

SWANSON: I think, generally, it’s been good. Now, it depends on what side you’re on. They also look into jail deaths. And a gentleman just won the Pulitzer Prize, a newspaper editor down in Palestine, Texas, writing about jail deaths in his county. The Rangers investigated them. They found that there was some negligence. But the local authorities, you know, failed to act, failed to indict anyone. I think it’s been the same with police shootings. There hasn’t been, on the whole, a tremendous amount of criticism of the Rangers’ investigations. But after that, the ball often gets dropped not just in police shootings but in police misconduct. You know, the Rangers aren’t the only actors here. They do their investigation. They send it to the DA and sometimes the DA indicts and sometimes the DA doesn’t. It’s a fairly new function for the Rangers, so I think the history is certainly still incomplete on that.

DAVIES: The Rangers are coming up on a big anniversary, right? 2023 will be their…

SWANSON: 200th.

DAVIES: … Two-hundredth anniversary.

SWANSON: Yes.

DAVIES: You said that they’ve played a major role in the past in burnishing their image, you know, insisting on approval of movie scripts and the like. That still going on? I mean, how are they reacting to the book?

SWANSON: Well, I don’t know. They haven’t talked to me about the book yet. But they didn’t talk to me when I was writing the book either. I made multiple attempts to speak with Ranger officials. I emailed. I called. I wrote the top Ranger a personal letter and sent it to him by US mail. And they wouldn’t talk to me at all. So they’re maintaining their silence thus far with the book, too. Now, as far as celebrating their 200th anniversary, oh, yeah, they’re going to do that. And they need — they’ve got to walk a line here, but they need to, I think, acknowledge what’s happened in the past but celebrate their greatness and their longevity and not dwell on the less favorable stuff. But I don’t think they can get away with ignoring it this time.

DAVIES: I assume you spoke with some Texas Rangers as you researched the book. I wonder if any of the older ones expressed any regret about what the Rangers were up to.

SWANSON: The ones that I talked to, no, not at all. They believe the Rangers were the good guys. As one of them said, the Rangers wore white hats. The good guys wore the white hats. The Rangers were the good guys. I did not run into a lot of introspection on the part of former Rangers. And that’s just part of the way the Rangers have always operated, I think. They hue (ph) pretty close to this ideal when it comes to public statements and public presentations. You won’t find a lot of Rangers — or at least I didn’t, older Rangers or those affiliated with the Rangers from way back — who will talk about the other side of things. They are very much devoted to the stereotypical Ranger image.

DAVIES: Well, Doug Swanson, thank you so much for speaking with us.

SWANSON:Thanks, Dave. It’s been a pleasure.

DAVIES: Doug Swanson is a veteran investigative reporter and editor. His new book is “Cult Of Glory: The Bold And Brutal History Of The Texas Rangers.” Coming up, critic Kevin Whitehead talks about jazz in the movies. It’s the subject of his new book, “Play The Way You Feel.” This is FRESH AIR.

Copyright © 2020 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.