Vietnam War Vet Lee Thorn: A Peace Activist Who Aided Laos

Kevin Fagan / San Francisco Chronicle

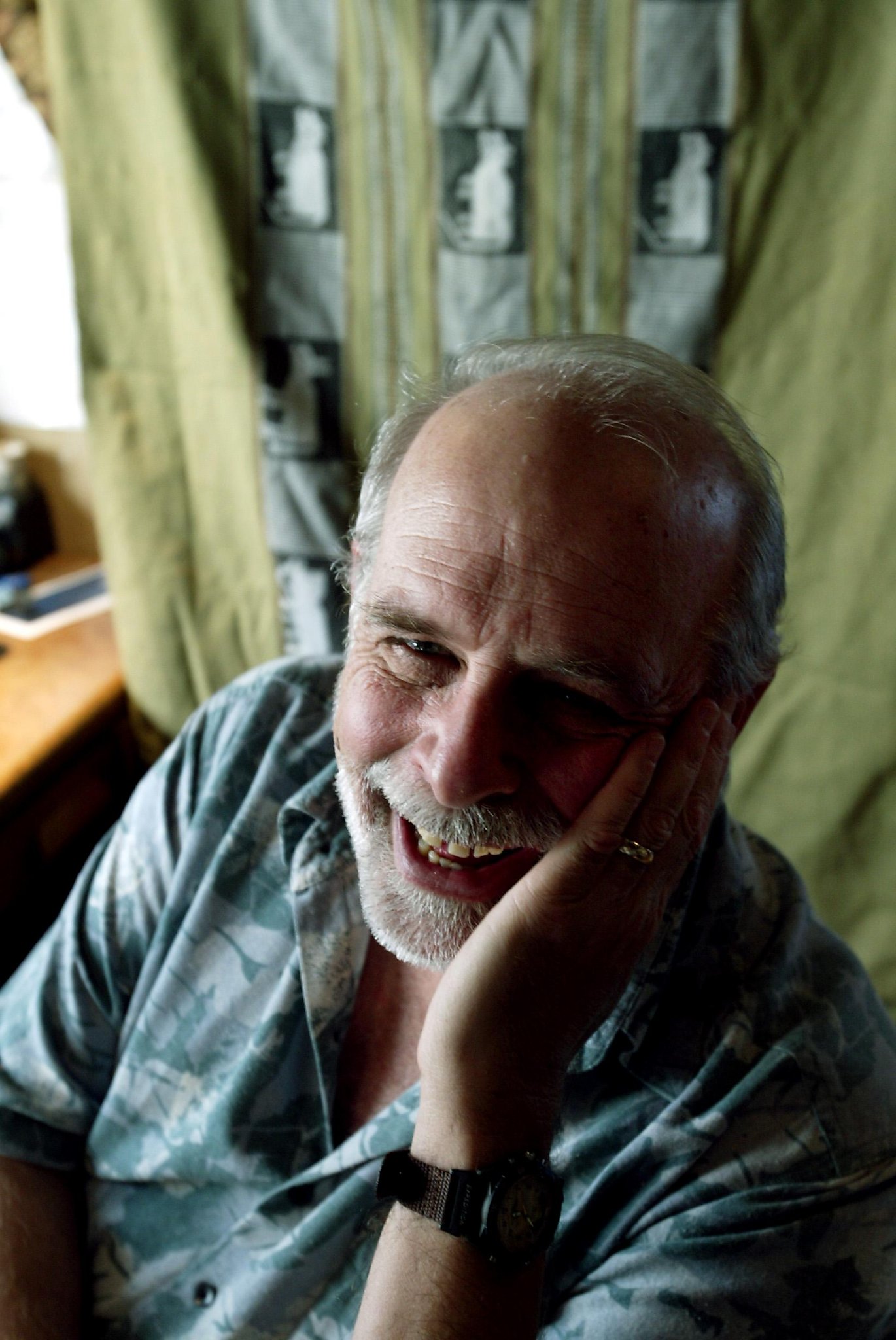

(July 1. 2020) — The Vietnam War left a terrible mark on Lee Thorn, searing him with post-traumatic stress disorder from guilty memories of loading bombs onto jets to rain fiery death upon Laos. So he left a mark in return.

After mustering out of the US Navy in 1967, he co-founded Veterans for Peace and then devoted his life to trying to heal the impoverished nation he helped devastate all those years ago.

Throughout decades of tireless campaigns, Thorn uplifted poor villagers in Laos by installing pedal-powered computers and supporting jungle coffee farmers, medical clinics and bomb-clearance campaigns. Just before he died of cancer at 77 on June 25 near his San Francisco home, some of his final words were about the country he had come to adore.

“I tried to do the best I could to make up for what we’d done there,” he told The Chronicle by phone from his hospice bed at the San Francisco VA Medical Center, where he died. His voice was barely perceptible, weakened by the disease. “I wish I could have done a lot more.”

When reminded of the efforts he’d made and how he had overcome the homelessness and alcoholism he sank into after the war, he managed a chuckle.

“Yeah, it’s been a pretty good ride, hasn’t it?” he whispered.

Thorn made his first stride into activism after his 1967 honorable discharge from the Navy when, as a student at UC Berkeley, he co-founded the Veterans for Peace group. A forerunner of the veterans anti-war movement, the group grew to 65,000 members by 1972, as Thorn combined efforts with fellow Vietnam veteran and future Secretary of State John Kerry and activist-singer Joan Baez. When it later merged with Vietnam Veterans Against the War, Thorn settled into a career as a community organizer for peace, disability rights and anti-poverty causes.

In 1998, he read a newsletter article by Bounthanh Phommasathit, a Laotian woman who had fled the village of Phon Hong in the 1970s to become a social worker in Ohio. She wanted to help her people back home. Thorn and a friend stuffed backpacks with medical supplies, delivered them to Phon Hong, and the widespread reaction by veterans and Laotians was so positive he founded the Jhai Foundation with Phommasathit’s help.

Jhai means “hearts and minds working together” in Laotian, and until its recent closure it provided economic and technical help to poor villages throughout Laos. Its biggest moment came in 2003, when Thorn recruited tech pioneer Lee Felsenstein to create a computer that could be powered by bicycle pedals and communicate through Wi-Fi cards tacked to mountaintop trees.

The idea was to give Internet access to Laotians living in huts with no electricity so they could find current prices for rice, silk and chickens and not be lowballed by city buyers. Thorn and Felsenstein — who invented the Osborne 1, the world’s first portable computer — led a team to Laos to install the so-called Jhai Computer, and after several tries the Jhai took hold as the first pedal-powered wireless computer designed for Third World villages.

Thorn expanded his efforts in Laos to include exporting coffee beans to America, installing wells, and supporting efforts to clear unexploded bombs and mines from the countryside. US forces dumped 2 million tons of bombs on Laos, making it the most heavily bombed nation per capita in history.

Asked what disturbed him most about participating in the Vietnam War, Thorn would say it was his hitch on the aircraft carrier USS Ranger loading cluster bombs and phosphorous rockets onto warplanes headed over the ancient Plain of Jars and other targets in Laos.

At night, he screened on-board films of the sorties.

“Guys would die, and I would close down inside a little more each time,” Thorn recalled. “What we were doing, killing that many people from the air, broke something inside of me.”

Thorn was born in Kansas City, Mo., to Lee Everett Thorn II, a movie theater executive, and Shirley Thorn, a school nurse. After his Navy service and as he built his career as an activist, Thorn married, divorced, and struggled with homelessness and alcoholism before getting clean and earning an MBA at the University of San Francisco. In 1988, he married Bernadette McAnulty, and they remained together in San Francisco until his death.

“My dad understood that real change in the world is what matters,” said Thorn’s son, National Public Radio host Jesse Thorn.

“To have unconditional acceptance in the place where he went to seek forgiveness and reconciliation, and to know his work engendered gratitude and not resentment, meant so much to him,” he said. “And I felt it when I went to Bounthanh’s village in 2005, and everyone treated me like I was their child.”

Michael Blecker, director of the veterans aid group Swords to Plowshares, said Thorn did other vets with PTSD a service by being so open about his struggles — and did everyone else a bigger service with his reconciliation work.

“Lee was the real deal in every respect as someone who was tormented, tortured by what he went through,” Blecker said. “He did his homework and made sure he understood the story. He was an activist, a scholar, a organizer. His fingerprints are everywhere in the efforts to heal from the war.”

Thorn is survived by his wife; his sons Jesse of Los Angeles, John Thorn and Brendan Thorn of San Francisco; and three grandchildren.

Services are pending.

Kevin Fagan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer.

A Soldier’s Solace / One Vietnam Vet Finds Redemption Growing Coffee in Laos

Kevin Fagan / San Francisco Chronicle

PASKSONG, Laos (August 17, 2003) — In the early morning, when the thin, silky fog hugs the mountains and the rise-and-fall lilt of Laotian filters out from the bamboo-and-stick houses of the village, everything seems as it used to be.

It was like this a half-century ago — before the Americans’ B-52 bombers rained hell day and night like brimstone slid from conveyer belts, making flames of children and coffee trees and water buffalo. Before the villagers fled to caves. Before they came back to rebuild, stick by stick, rice paddy by rice paddy.

Back then, the farmers say, morning in these 4,500-foot-elevation coffee- growing fields of the Bolaven Plateau was quiet, the handmade thatch-roof houses and dirt roads seeming as timeless and calm as the Lao people themselves. Simple. Gentle.

Lee Thorn sits in a dusty field outside Paksong, the only town in this region of little coffee villages scattered throughout the high jungle, and he closes his eyes to block out the rising sun. A few years ago, visiting the darkness in his head like this, even awake, might have brought on the nightmares that had haunted him since his days in 1966 as a Navy bomb loader for warplanes headed for these mountains. In these nightmares, he could see rockets detonating, killing families, villages, his own children, and if they were particularly bad, he would lurch to his feet screaming, in cold sweats.

But now there is peace. It is a peace the 59-year-old Navy veteran from San Francisco has built, moment by moment, since 1998, when he flew here and offered to do anything he could to help this country he and his comrades-in- arms crushed so long ago. And on this particular morning, Thorn is getting ready to inspect the biggest load of coffee beans ever shipped in modern times from Laos to the United States, and it carries the name of the organization he created to help Laos: Jhai Foundation.

For just a minute, after all the bustle and nail-biting of the past six months in getting this coffee harvested and ready in one of the poorest nations on Earth, he savors it all, eyes closed.

“If you’d told me years ago that someday I would be here, doing this and feeling like this, I would have said you were crazy,” he says slowly. “Hell, I was just this crazy vet, trying to put one foot in front of the other. I didn’t know if I’d live to see 30.

“But today?” Thorn opens his eyes and takes in the sunrise. A big smile spreads over his face. “Today, life is beautiful. These people are beautiful. And our coffee — it is absolutely beautiful.”

On this day there will be plenty of hard work to do, to be sure. Before nightfall, Thorn and the coffee crew from Jhai will tromp for miles through thick jungle stands of bamboo and mahogany, kicking aside land-leeches and grasshoppers leaping at their legs all the way, to inspect coffee trees that will hold next year’s crops. They will rumble from farm to farm in a tok-tok (a motorcycle souped up to be a tractor), rattling dozens of miles down dirt roads so cratered by monsoons that normal cars can’t go 10 feet without throwing an axle. And finally, there will be the inspection, bag by bag, of the 10 tons of coffee beans Jhai is shipping to California.

But for Thorn and his foundation crew and the hand-to-mouth coffee farmers they are paying — with more dollars than these farmers have ever seen — it might as well be play. This work is being done from the heart.

Certainly, this is about making money for poor farmers who make at best a couple of hundred dollars a year, for the Jhai Foundation’s other projects, and about introducing Laotian coffee to the United States. But even more important for Thorn and his partners, it’s all about making “reconciliation” to Laos — a veterans’ activist term for helping out the country you once waged war upon.

“Mr. Lee! Mr. Lee!” the children and villagers cry when he strides up to a group of thatched-roof houses to ask how the shipments have gone. “Coffee!” Although the villagers are as poor as the rough wooden floors many sleep on, there is an instant welcoming for friends and strangers alike. Maybe it’s the Buddhist bedrock of Laotian culture, but the people seem to have acclimated to their limited, economically backward lives so well that there is a tender acceptance of all things living that springs forth on their faces every time they meet Thorn and his comrade falang, or foreigners.

In his several years of journeying here to help these farmers, the sweetness never gets old for Thorn. With a big grin, he grabs the kids by the shoulders, poking them playfully, and asks in broken Laotian how the farmers’ wives and brothers have done since the beans were bagged a couple weeks before.

The two sides can barely understand each other, but as they stand together in a dirt yard ringed by fences made of stripped tree branches, the talking is done with gestures.

“My relationship to the Lao people in the war was abstract,” Thorn says. “I knew I was helping defeat communism, and that I could kill them. The whole point was that we’re better than them, we can defeat them. But it was stupid — thinking purely like that, with only war in mind, leads to more war, no economic development and a lot of dead people on all sides.

“The only way I could heal was to see them, and have them see me, as whole human beings. When you are in a war, there is no relationship. It’s all about destroying things.

“This,” he says, chucking a 5-year-old girl under the chin, “is the opposite of that. This is relationship. This is reconciliation.”

“Mr. Lee, stay and talk?” the girl’s mother asks. “No work now?”

He shakes his head. “Still more bags to look at, more trees,” he says. “Later, we party for the harvest.” The woman understands just enough, and clasps her hands together in the Buddhist gesture of respect.

Thorn has been doing a lot of reconciliation here. For five years.

Most recently, Thorn and a Jhai Foundation team of computer engineers and technicians gained worldwide notice when they came within a whisker of installing the world’s first bicycle-powered, wireless computer in Phon Kham, a remote village hundreds of miles north of Paksong. The Jhai Computer was invented by Silicon Valley pioneer Lee Felsenstein to help the villagers, who have no power or phone lines, better sell their rice and silk and talk to long- departed relatives — and it was two days short of being started up in February when a power surge fried two hard drives.

The people of Phon Kham, confident that the computer will be fixed and back for another try, threw a big party anyway, cooking up an entire water buffalo and showering the Jhai team with gratitude for even trying. The two Lees, Thorn and Felsenstein, brought the little computer back to the Bay Area for repairs and plan to go back to Phon Kham by fall to give it all another try.

Which brings us to the coffee.

Thorn runs Jhai Foundation and its staff of more than 75 people in the United States and Laos — mostly volunteers — out of his basement in San Francisco on about $200,000 a year in grants and donations. One of his biggest goals is to make everything he does in Laos self-sufficient. So when he cast about for money to pay the $9,000 startup costs of the Jhai Computer, and the thousands that will be needed to keep it going in years to come, where did he look?

In Laos, of course. In its coffee fields.

“We can have one help the other, the farmers make money, and everyone wins, ” Thorn says. “That’s the hope, at least.”

It turns out that although few people other than Thorn would know it, Laotian coffee beans have historically been regarded as among the finest on Earth. And even though the market for them is practically nonexistent today — only 16,000 tons were exported from Laos last year, mostly to Europe, compared to 900,000 tons from next-door Vietnam — the quality of its best hasn’t diminished a drop.

Last year, tasters working with the prestigious CIRAD coffee research institute in Montpellier, France, pronounced Laotian beans to be among the 12 best coffees in the world.

The French first brought Arabica Typica beans — the finest of the finest — to Laos in 1930, when it was their colony, and for years the country reigned supreme as a fount of top-notch coffee. Most of the beans were, and still are, planted in the Bolaven Plateau in the southern half of the country because of its ideal terrain: tall, shady jungle trees, elevation above 3,000 feet (which cuts out most coffee tree diseases), and rich, volcanic soil perfect for nourishing beans.

This, however, was before rebellions that led to the French being heaved out of the country in 1954. That was followed by the United States’ war to try to oust the communist Pathet Lao, beginning with CIA advisers in the 1950s and peaking from 1964 to 1973 in a nonstop aerial assault that turned Laos into the most bombed nation, per capita, in the history of the planet.

The wars, combined with a few devastating bouts of “rust,” a coffee-tree disease in the lower elevations, stripped Laos’ once-mighty coffee fields down to a few thousand acres by the 1970s, and the market lay fallow until the mid- 1990s.

That’s when the government started encouraging coffee farmers, few of whom run farms of anything larger than a few acres apiece now, to grow again. It wasn’t hard to restart: The broad-leaved trees, looking a bit like bottle brushes and peaking at about 10 or 15 feet in ideal height, had been growing wild everywhere all along. All it took, in many cases, was clearing away the underbrush so you could tend the trees or plant new ones alongside the old ones.

Not long after that, do-gooder Thorn showed up. The Bolaven coffee knocked his socks off, he saw a potential market, and before he knew it, he had another project on his hands. More importantly, he soon also had a buyer in California, like-minded Thanksgiving Coffee of Fort Bragg, the social-activist specialist coffee importer that is to coffee what Ben and Jerry’s is to ice cream.

Thanksgiving Coffee CEO Paul Katzeff always relishes an underdog — he imported coffee from Nicaragua when the United States supported the Contras, donating part of the profits to the Sandinistas to thumb his nose at the Reagan administration. He’s been like that since founding the company in 1972. He is also the immediate past president of the Specialty Coffee Association of America, the largest coffee trade association in the world, “So I know what I’m up against when I take on a new coffee,” he says with a hearty guffaw by phone from Fort Bragg.

Much of Katzeff’s year is spent roaming the globe hunting for specialist coffee beans he can buy so he can sell cool roasts in the United States, but also donate part of each bag’s profit to causes he likes. The result has been a product line split into many banners, with names like “Song Bird Coffee” (aiding the American Birding Association) and “Eco Boom Coffee” (benefiting marine-life education).

This time, though, the new coffee came to him, courtesy of Thorn’s research in the progressive community for a coffee buyer who would have not just economic legitimacy but the right attitude.

“Jhai Coffee” will be the name, and profits after Katzeff’s thin cut of about 3 cents on the dollar will go to help the Jhai Foundation’s works in Laos. Katzeff is paying Thorn up to $2 profit per pound sold, and he will stock the Jhai label in Safeway stores and on private specialty-coffee lists.

In turn, Thorn is paying the small farmers he dealt with in the Bolaven Plateau — about 130 in all — up to $1.35 a pound for their coffee. That’s not only slightly above the global Fair Trade price, but quadruple what Laotian coffee growers usually get.

“Eventually, if he and I do this right, we can put Laos on the map for coffee,” said Katzeff. Even though Laos has some of the most historically prized coffee in the world, he said, its market is practically nonexistent, “so the market is ripe for developing.”

It’s the first time anyone in the Laotian or American coffee industry can remember that a large load of Laotian beans has been marketed in the United States. Even in the French heyday, the beans went to gourmet cups in Europe.

“Lee is about changing things for the better, and he’s the real deal,” said Katzeff. “If anyone can do this, he can. And so can I.”

Thorn started his coffee adventure small two years ago, buying coffee beans himself and selling 1-pound bags to supporters and friends in America. But that’s just his latest thing.

His efforts to help Laos really began in 1998.

That’s when he and his best friend, Rich Stoll of Pleasant Hill, loaded two backpacks with 200 pounds of surplus medical supplies and took them to a clinic so poor that wind whistled through its cracked walls. It had been three decades since Thorn’s days as a bomb loader on the Ranger in the Tonkin Gulf — and despite earning an MBA at the University of San Francisco, despite co- founding Veterans for Peace, despite shaking his ’60s-era love for drugs and booze and creating a family of wife and three kids, there was one ache he couldn’t slake.

There were the nightmares, the shakes, an inability to sleep through the night. There were flashbacks about loading cluster bombs and phosphorous rockets onto bombers and jets headed over the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the Plain of Jars, and scores of other targets in Laos, and seeing them come back empty, knowing hundreds had just been incinerated in tiny villages. His job back then was screening on-board films showing the effectiveness of the air strikes; the images are never far from his mind, even today.

It was classic post-traumatic stress, doctors told him. Eventually he realized that no matter how much he accomplished in his civilian life, he had to go stare his terror down right where he had killed, or he would never be free.

So when he read a story in a veterans’ newsletter pleading for medical supplies in Phon Hong, a village about 50 miles outside the national capital of Vientiane, he made his move.

The newsletter article was written by Bounthanh Phommasathit, a Laotian who had fled the village in the 1970s and was — and still is — working as a human services consultant in Ohio. He called her up, scored the medical supplies through his peace activist network, and got on a plane with Stoll, not really knowing what he’d find when he got to Phon Hong.

What he found was personal absolution.

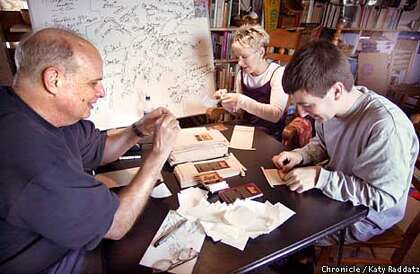

Lee Thorn and young volunteers work at labeling packets of Laotian coffee.

Bounthanh and Thorn met in Phon Hong, Thorn with his supplies and Bouthanh with her hopes for the clinic that serves the family she left behind, and they became fast friends. The supplies — basic things, like needles and colostomy bags — made a real difference. That did it.

The nightmares were snuffed. Thorn has been going back ever since.

“There have been times since the war that I thought we’d never see him again,” says Stoll’s wife, Lorna, who, like her husband, has known Thorn since they were all kids growing up together in middle-class comfort in Glendale (Los Angeles County). “We’d put him on planes for some big peace rally, and he’d be so messed up with drugs or PTS (post-traumatic stress) or whatever that I thought he’d die in a hotel room somewhere.

“But he always wanted justice. He always wanted to do the right thing. He just needed to find out how to get out of his box. He needed Laos.”

The partnership between Bounthanh and Thorn led to the Jhai Foundation, which in five years has shipped 10 tons of medical supplies to Laos, dug wells,

installed computer learning labs for children, repaired school buildings — and now, has started shipping coffee to the United States.

“We truly ask people what they want. We don’t start anything until we have a friendly relationship,” Thorn says. “I’m a Vietnam vet, so I know what unfriendly is. My partnership with Bounthanh led me to her people in the villages, and on our second trip Rich and I had a translator who grew coffee. So we went to look at that.

“You see, one thing just leads to another.”

Particularly if you are as fiercely directed as Thorn. Once his interest in coffee was sparked, he started asking around about who sells what and where and to whom, and he quickly wound up in Pakse, the capital city of the province that includes the coffee fields. There he went to the home of 80-year- old Bounlap Nhouyvanisvong, the dean of Laotian coffee.

Bounlap has grown coffee since the French ran things in the 1930s. When Thorn met him he was president of the Lao Coffee Exporters Association, and he is now the president of the Lao National Chamber of Commerce. Bounlap had the knowledge, and he had the juice to get Thorn started, but before he started advising, Boulap took Thorn to Paksong in the heart of the Bolaven Plateau. There, he brewed him a cup of coffee from beans picked straight from the fields and roasted on the spot.

“First he tried coffee in a normal cafe in a town, and it was not so good. But when I took him to Paksong and he tasted it pure, he said, ‘Wow!’ ” Bounlap recalls at a meeting in February to help Jhai strategize how to get organic certification from America and Europe. The certification shouldn’t be too hard to get since Bolevan farmers are too poor to grow any way other than organic.

“It’s what everyone says once they taste real Lao coffee,” Bounlap says. “We have the best, but hardly anybody knows it.”

By pure serendipity, Bounlap and other Bolaven farmers have been trying since the revival of the coffee market in the 1990s to get Arabica back on the map.

Robusta, the cheaper and less tasty bean in the coffee world, constitutes the bulk of the coffee being grown in Laos right now — which isn’t much. But the French Arabica beans planted so many decades ago are still growing wild in the jungle where they started, on farm plots high in the mountains, and that is what Thorn is now buying.

This is anything but easy. The problem isn’t deciding you want Arabica. It’s actually getting your hands on it.

The Bolevan Plateau is pretty much as it has been for centuries: dirt roads laced into the mountainous jungle, with tiny farms of a few acres apiece dotted throughout the trees. Until the past few years, carts pulled by cows were the main form of transport.

Motorcycles, tuk-tuks (motorcycles rigged to be rickshaws) and tok-toks have become pervasive since the mid-1990s, thanks to cheap imports from China. But the roads are still so rutted from monsoons that they are nearly impassable much of the time. The average gas station is a wooden table stacked with used water bottles filled with petrol, rags jammed in as corks a la Molotov cocktails.

Thorn’s foundation manager in Laos, Vorasone Dengkayaphichith, and Vorasone’s brother, Ariya Dengkayaphichith, headed up a team of about 50 workers last fall to score the beans. This meant tok-tokking from farm to farm,

day after day, to inspect coffee loads harvested that day and laid out for inspection. They chose only “cherries,” or nice bright beans with no holes or blemishes.

Once bought, the beans were dried in one of the villages on wire-mesh racks Jhai had specially made. Most farmers dry on tarps on the ground; using wire racks is an old French method that ensures purer beans. Then they were taken to a processing plant down from the mountains near Pakse, the nearest big city to the plateau (about 50 miles away), where the skins were peeled off, the beans were weighed and sorted by size, and poured into 132-pound burlap bags.

It is these bags, 157 in all, that Thorn and Vorasone are inspecting today. From here they will go to a ship in Thailand that will take them to Thanksgiving Coffee in Fort Bragg. If there’s anything wrong, it had better be caught right now.

“No matter how careful you are, you wind up having to throw many out,” Vorasone mutters, digging his hands into a bag and pulling up a pile to smell and peer at intently. “We bought about 60 tons of cherries, and we got 10 tons of good beans from that — that’s normal.”

A bucketful of beans at the top of one bag still has some husk clinging to it. Vorasone is on it like a panther on raw meat, and orders it back to the whisking machine.

“Now here are our best, and we are still looking them over,” he says. “You still need to be a perfectionist. You look them over right until they go onto the ship.”

The main buyers for Laotian coffee in recent years have been Thai and Vietnamese traders coming through to snap up cheap bulk. This year, however, nearly half the tiny total of exports from Laos is heading to California — Jhai’s 10 tons are bound for Thanksgiving Coffee. The farmers feel the greatest hope they have for decades.

“Twenty-five years ago I began farming again, after the war died down enough,” says Nommala Thepboualy, chief of Phon-Ouy village — the main village that Jhai deals with. “I’m very glad to explore the American market now. Right now the brokers that pull through, they don’t pay us fair prices, and we had no way to sell to other people. Until Mr. Lee came here.

“Now, we have a future.”

Jhai Foundation (Photo: David Sanger)

Phon-Ouy, like every other village here, was bombed flat in the secret air war of the 1960s and ’70s. Nommala and virtually every other man here had to flee as every aerial horror the US military could summon up killed, maimed and burned to ashes anything standing.

Today, there are still so many UXOs — UneXploded Ordnance, usually tennis ball- size “bombies” from cluster bombs — all around that every time someone tries to cut space for a new house or coffee field, a leftover bomb turns up in the dirt.

“Just last year, one of our people died, cutting weeds on his farm,” Nommala says matter-of-factly. “He hit a bombie with his machete. They are everywhere.”

Nommala solemnly displays nine black dots tattoed onto his right arm, seven on his other: “Good luck,” he says. “Protects me from dog bite, knife stabs. And bombies.”

Thorn stands next to the chief, hears the story of bombie death — a story he has heard the like of all over this country — and he puts a hand on the chief’s arm. “I am so sorry,” he says, voice almost a whisper.

“There is nothing for you to be sorry about, my friend,” Nommala tells him, a big grin leaping to his face. “The war — it is gone, disappeared from my mind. The children all came, the years went by, we deal with the bombs every day. And now America even comes to help. You, Lee Thorn, you come to help.

“There is no sorrow.”

An hour later, as Thorn rattles in the cart of a tok-tok heading from one farm to another, Nommala’s words still resonate in his mind. The red dust of dry season, an ever-present, choking cloud on every dirt road in the country, swirls around him as the tok-tok roars across the smallest of the road’s craters, bouncing crazily with every dip. Chickens, kids, cows and everything else on legs wander at will all over the place, stopping the tok-tok every few hundred feet as they saunter across the road.

“These are heavy people, man. Good people,” Thorn says. “They always, always make me think and make me grateful, and make me remember what I have to do.”

Thorn shakes his head, laughs as the tok-tok screeches to a stop in the dust for a water buffalo.

“I remember talking to Kurt Vonnegut once many years ago, when my post- traumatic stress was fresh, and I asked him, ‘You went through the firebombings and all that crap back in World War II, and how do you cope?’ ” he says. “He told me, ‘Just be honorable.’ ”

The tok-tok roars back into life and rattles across a one-two-three series of jarring potholes. Thorn appears not to notice, lost in his recollections. “It’s the truth, man,” he says slowly, after a moment. “You can choose to be honorable, or not. It’s a choice.

“That’s why I’m here. It’s for me, and for people like Mr. Nommala.”

Thorn is instantly readable for who he is, T-shirt hanging out of pants and quick laugh on his lips, whether he’s rattling along in a tuk-tuk or lounging on the couch with his kids back in San Francisco.

At 59 years old, there is nothing left to hide, everything to gain and no time for bull-, he’ll tell anyone who asks. Born in Kansas City as the son of a Marine, he went to war as many young men filled with idealism did, but came out damaged — and that has set the tone, like it or not, for the rest of his life.

It even determined, to an extent, how he married. Bernie, his wife, is a Belfast warfare survivor from Ireland. Thorn found he felt most comfortable marrying a woman who, when they got their battered Victorian house in San Francisco, took different routes home every night out of habit. That’s how she walked at home, so terrorists wouldn’t trace her steps.

“You never shake the habits all the way,” says Bernie, who met Thorn in the 1980s, when they were both in alcohol rehab. “Belfast, Vietnam — it’s all the same in one way or another.”

“I need people around me who can relate,” Thorn says with a chuckle. “And who, like me, realize you have to live now, because life is too precious to waste.”

The only time the air of quiet joviality diminishes for Thorn is when he is focusing hard, running a meeting of the techies or the farmers or trying to unsnarl a problem. Then his face goes dead serious and his eyes hone in like a laser on whomever is talking.

It’s the same intensity that enabled him to corral widely varying personalities together in the late ’60s at UC Berkeley when he co-founded Veterans for Peace. Crazy days, vets of those days recall to a man — and having a guy like Thorn around was handy. He was so dogged he single-handedly kept singer Joan Baez attached to the movement when splintering factions threatened to alienate her.

But even then, as now, his management style was, as he says, “to bring the smart people together, help set a direction and then let them go.”

The Jhai Computer project is a perfect example. Thorn recruited Felsenstein,

and the two Lees then recruited two-dozen computer specialists and technicians from contacts or over the internet techie chat sites. Some of them ditched jobs with IBM and Microsoft, others were between tech consultant gigs, and for the first failed attempt, they all either phoned in help or flew into Laos from around the globe with the Jhai Computer system parts.

“This is not a financial thing for him,” marvels Felsenstein one day during the run-up to the failed “launch” of his Jhai Computer. “He just gets this great satisfaction from helping people. I can relate.”

Most of the time, everyone at Jhai is too busy to reflect on this sort of thing. But finally in early February, there comes a time for the coffee crews to sit back and take in the comparative enormity of what is being done here, step by step.

After the months of planning and buying and picking and processing, the harvest is truly done and the beans are headed for California. The bags Vorasone and Thorn inspected have been trucked to a port in Thailand. The villagers decide it’s time for a Laotian hoedown to celebrate, and since more than 100 farmers and workers are in on it, this will have to be a two-cow party — big doings in little Phon Ouy village.

Early in the day, the men kill the cows and the women start cooking. By nighttime, everything is hacked into hand-size hunks — riddled with bone splinters from being chopped up rough, but tasty from roasting over a fire. There is plenty of sticky rice in cups, and the women pour endless glasses of home-brewed Lau-Lau (rice moonshine with a mean kick) from detergent bottles, motor oil bottles, or anything else they found to stow the liquor in.

“This year, we ship 10 tons of beans. Next year, 18!” Thorn yells to the farmers after everyone is well-lubed on Lau-Lau and cow chunks, a translator transmitting his words.

“Jhai! Yes! Jhai!” the crowd roars.

“Growing coffee is better than being soldiers, yes?” Thorn yells.

The men — virtually all of whom carried rifles in the bloody old days — laugh when they get the translation. “Yes! Coffee!” they shout back.

Bauane, an old man in an even older-looking Laotian Army fatigue jacket, throws his arms around Thorn, and Thorn’s face lights up.

“I am a vet like Mr. Lee, I fought in the same war,” Bauane — no last name, in ancient back-country custom — says to Thorn’s translator. “We all went through hell. So much death. And now what he does is good.”

He stares at Thorn, blinking from too much Lau-Lau, struggling to find just the right words. “Before Mr. Lee, no work. Now, work! War is over.”

Thorn stares straight back, then around at the dozens of giggling little kids, prancing around his legs like breaking waves. A band at the front of the party’s wide dirt yard breaks into a Laotian version of the old Bee Gees hit “To Love Somebody” and as he recognizes the tune, a tear breaks loose from his left eye and rolls past his huge, loopy grin.

“I feel like this is family,” he whispers to nobody in particular. “I’m home.”

Bombs Into Machetes

It’s a hot midweek day, and Lee Thorn is rumbling in a truck up to the southern coffee fields to check the crops. This is happy stuff, productive stuff, nothing to do with war memories and sadness, and he and his crew joke and laugh as the bamboo huts roll by the windows.

Then they stop at a little village along the way to chat up the locals and check out a rumor. Folks say this is a blacksmith village, and that the metal the smithies use comes from bombs left over from that war so many years ago. It’s a common thing. Remote villages all over Laos are so dependent on leftover bombs for metal that silverware and pots everywhere are made of it, and hunters pick them apart so they can use the powder and ball bearings in their homemade flintlock rifles.

But this turns out be something more: Turns out the dozen smithies here don’t just use the metal, they use live bombs as anvils, pounding on them with their crude hammers. Every so often one of them is blown up.

Thorn approaches the village’s main workbench with his usual broad grin. “Hello,” he calls out, then his face freezes when he sees the setup. One guy is pumping empty rocket flare tubes as a makeshift bellows, another is banging on a fat howitzer shell as an anvil, and chunks of mortar rounds, cluster “bombie” bits and other ordnance lie in piles around the shop.

“Are these the bombs that Americans dropped?” Thorn asks quietly. The men nod. “A-10 planes came in here, big flashes when they dropped?” The men nod again, and begin to chatter about how everyone ran when the big US planes flew overhead, and everything not hidden — including the cows — died, and there was fire everywhere.

The jaw muscles work in Thorn’s face and he stares at the dirt. “I used to load planes like that,” he says, voice flat. Then men grin reassuringly, shrug.

“We were veterans, too,” one says. “Long time ago.”

Thorn points to an anvil. It’s a 155mm howitzer shell. “Bomb?”

“Bomb? Yes! Good anvil,” says 59-year-old Keung (who uses no last name, an old-country Laotian custom), and he gives it a terrific bang with his blacksmith hammer. He’s making a 2-foot machete out of melted-down bomb fragments, and as he pounds, his partner, 34-year-old Pyung, pumps the rocket shell bellows to heat the forge.

It’s still packed with powder, the men say, a fact later confirmed by local bomb-clearance experts, who try in vain to get the smithies to stop using live bombs. Taking the powder out makes the shell weaker and no good as an anvil, the smithies say; the clearance experts have no authority to take the stuff away.

Pyung’s bellows are two US phosphorous flare tubes, serial numbers and English instructions on how to set the fuse still clearly printed on their sides.

Asked why he would pound on a bomb that could kill him at any moment, Keung shrugs. “Sometimes they go off,” he says. “We have no choice. These work better than the sledgehammer heads we have to use for anvils when we cannot find these shells.

“Plus,” he adds cheerily, “they’re free.”

“I wish every vet could see this in America,” Thorn tells the men. “Talk about swords into plowshares. I just wish you wouldn’t use the live ones.” They grin again, shrug.

A few months ago, Keung’s friend, Tear, wasn’t so fortunate, they say. His anvil exploded and took off much of his leg.

Thorn walks over to Tear’s house, only to find out Tear is in self-exile in the bamboo forest and can’t be found this day. But his daughter, Lea, takes him to see Tear’s forge — and there, on his workbench, sit his two new replacement anvils.

They are identical 155mm howitzers, packed with powder and ready to blow.

“What choice does my father have?” Lea says. She stares at the anvils, a tear sliding down one cheek.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.