Of Gut-listeners, Flying Fish, and Other Pretexts for Going to War

Jon Swan / Tikkun

(August 3, 2020) — Declaring war against a foreign country of one’s choice might be a tempting option for a commander-in-chief floundering on the home-front battle against an invisible enemy. Wrapped in the American flag, the leader becomes instantly bullet-proof. Meanwhile, producing evidence, or the illusion of evidence, of a grave threat to the nation’s security has proved to be a common hat trick among leaders of the free world.

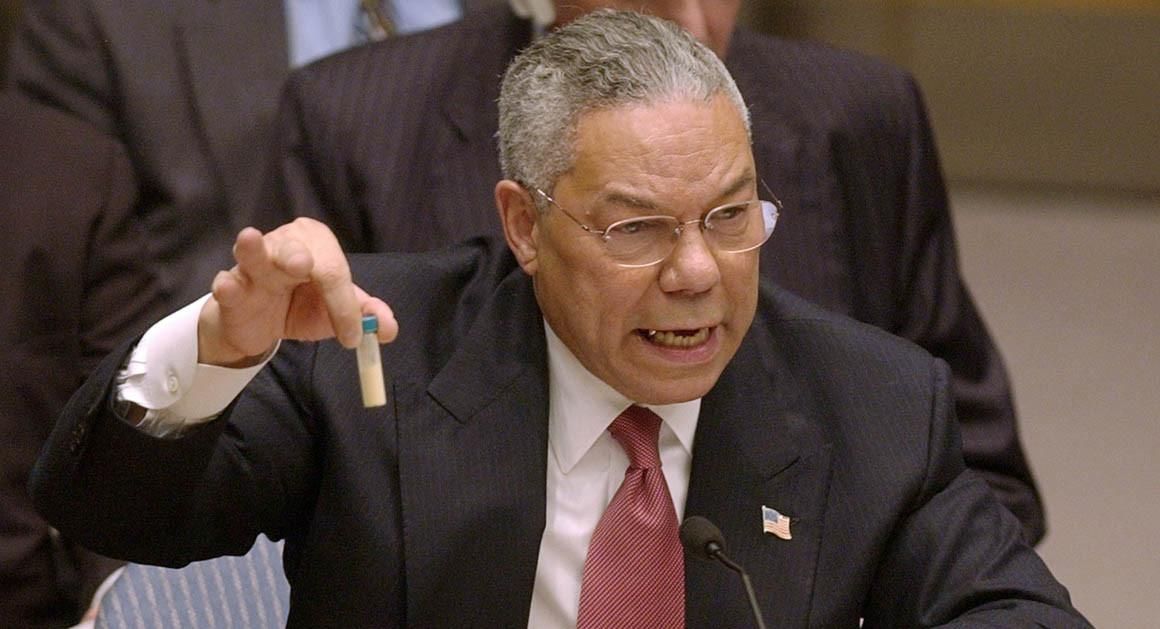

An infamous example is the “evidence” adduced by Secretary of State Colin Powell to justify the case for declaring war on Iraq. “My colleagues,” Powell said in his February 5, 2003, address to a plenary session of the UN Security Council, “every statement I make today is backed up by sources, solid sources. These are not assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence.”

Two years later, on September 9, 2005, a headline in The New York Times read: Powell Calls His UN Speech a Lasting Blot on His Record. The lead graph of the article, by Steven R. Weisman, stated: “The former secretary of state, Colin L. Powell, says in a television interview to be broadcast Friday that his 2003 speech to the United Nations, in which he gave a detailed description of Iraqi weapons programs that turned out not to exist, was ‘painful’ for him personally and would be a permanent ‘blot’ on his record.”

Three years later, in a May 2016 interview for Frontline, Powell revealed that, “at the time I made the speech [to the UN], the president [George W. Bush] had already made his decision for military action.”

Thus, clearly, Bush had been determined to go to war, regardless of the facts, with Bush subsequently explaining to Bob Woodward, as quoted in Woodward’s 2002 book, Bush at War: “I’m not a textbook player. I’m a gut player. I rely on my instincts.”

In short, the whole performance had been a charade.

Then there’s the example of the evidence on which the United States went to war against North Vietnam in August 1964, by passing the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which authorized President Lyndon Baines Johnson to take all measures necessary to protect the armed forces. The vote in the Senate was ninety-two to two in favor; in the House, support was unanimous.

The Resolution — interpreted as the equivalent to a declaration of war — was triggered by an incident that remained a subject of debate for more than forty years. The truth emerged with the release of the nearly 200 documents related to the Gulf of Tonkin incident and transcripts from the Johnson Library, as reported by Lt. Commander Pat Paterson of the U.S. Navy in “The Truth About Tonkin,” published in the February 2008 issue of Naval History Magazine.

The provocative incident in this case consisted of two separate, alleged attacks by North Vietnamese patrol boats on two U.S. Navy destroyers, the USS Maddox and the USS Turner Joy in the Gulf of Tonkin. The alleged attacks occurred on August 2 and August 4. Reconstructing the August 4 incident, Patterson writes, “Just before 9 p.m. that night, Maddox reported spotting unidentified vessels in the area. Over the next three hours, Maddox and Turner Joy were engaged in high-speed maneuvers designed to evade attack …. Maddox reported multiple torpedo attacks as well as automatic weapons fire. Both destroyers returned fire, launching multiple shells at the ‘enemy.’”

This account was flatly contradicted by Navy Commandeer James Stockdale, who was flying recognizance over the Gulf of Tonkin at the time of the alleged encounter. “Our destroyers were just shooting at phantom targets,” he reported. “There were no [North Vietnamese] boats there… There was nothing there but black water and American firepower.” Patterson further notes that Commander John J. Herrick of the Maddox, who had reported multiple torpedo attacks as well as automatic weapons fire, “later questioned his crew’s version of events, and attributed their actions on August 4th to ‘overeager sonar operators’ and crew member error.”

“[President] Johnson himself apparently had his own doubts about what happened in the Gulf on 4 August,” Patterson notes. “A few days after the Tonkin Gulf Resolution was passed, he commented, ‘Hell, those damn, stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.’”

Too late. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution had been passed. There was no turning back. No will to turn back. The war, begun in August 1964, lasted until April 1975, with the fall of Saigon. The casualties were astounding high: as many as 2 million Vietnamese civilians, on both sides of conflict, were killed, and more than 1.1 million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters. Between 200,000 and 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died in the war, as did more than 58,200 members of U.S. armed forces.

And then there’s the case of the Spanish-American war (April 21, 1898 – August 13, 1898), following an explosion that sank the U.S. battleship Maine riding at anchor in Havana harbor. Last year, Louis Fisher, for four decades a specialist in Constitutional Law at the Library of Congress, now a scholar in residence at the Cato Institute, provided a compact summary of “Theories of Why USS Maine Exploded.”

Fisher begins with the 1898 investigation conducted by the naval board of inquiry created by the McKinley administration; it came to two conclusions: first, that there was “insufficient evidence to assign blame to any person or persons,” and, second, that “the blast was caused by a mine placed outside the ship.” [Emphasis added]. However, as Fisher had observed in an earlier, more detailed study of the case, the board failed to make use of several technically qualified experts, among them the Navy’s chief engineer, who “suspected that the cause of the disaster was a magazine explosion” — thus, inside the ship.

Further, while the board of inquiry dismissed the possibility that an explosion in a magazine containing ammunition had sunk the ship because “there had never been a case of spontaneous combustion of coal on board the Maine,” Fisher points out that the board failed to acknowledge that “other U.S. ships had experienced spontaneous combustion of coal in bunkers.”

The sloppy investigation proved to be irrelevant. There were other reasons, or excuses, for declaring war on Spain. The Cubans had been fighting for independence for more than a decade and Americans were generally sympathetic with their cause. Under Cuba’s Spanish commander, General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, nicknamed “the Butcher,” Cuban noncombatants had been herded into “reconcentration areas” in and around the larger cities; those who remained at large were treated as enemies.

Thousands of the reconcentrados died from exposure, hunger, and disease — conditions that were graphically portrayed for the U.S. public in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. Thus, humanitarian concern for the suffering Cubans was added to the traditional American sympathy for a colonial people struggling for independence.

The slogan “Remember the Maine!” became the battle cry to which, on April 25, 1898, the United States enthusiastically went to war against Spain, even as Spain’s weak government sought to keep the peace by offering one concession after another. It was all too late.

There is more to be said about this one-sided conflict, but first it might be useful to consider the contagious idea of the concentration camp. During the South African, or Boer, War, between the British and South African (or Boer) War, which broke out in 1899, 115,000 noncombatant civilians, white Afrikaners and black natives, were confined by the British in segregated camps, in which nearly 28,000 white civilians and 20,000 blacks died. In 1904, the Herero of Southwest Africa (Namibia), a German protectorate, rebelled against the increasing cruelty of their rulers; the war and General Lothar von Trotha’s extermination order resulted in the death of an estimated 80,000 Herero and Nama men, women, and children, in battle and in concentration camps, with many of those incarcerated being used as slave labor or sex slaves and whose skulls were later used to support Nazi racial teaching.

The United States, for its part, which in the nineteenth century forcibly concentrated Native Americans in reservations, in 1942 confined for four years more than 120,000 law-abiding Japanese-American citizens following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Currently, a daily average more than 30,000 asylum seekers are being held in the U.S. in concentration camps euphemistically called detainment facilities, federal migrant shelters, or temporary shelters for unaccompanied minors, while several thousand children of the asylum seekers have been separated from their parents and warehoused in unhygienic and inhumane conditions, where limited testing has shown a positive rate of 50 percent for COVID-19 among detainees.

By June 15, according to the Center for Migration Studies of New York, the virus had spread to sixty-one facilities and to forty-five detention employees. As a recent article in Intercept noted: “Physicians for Human Rights, a U.S.-based nonprofit that investigates human rights violations around the world, found that the policy of family separation — which officially ended in the summer of 2018 but continues today — ‘constitutes cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.’” In other words, torture.

Compounding the cruelty of incarceration, the Center for Migration Studies of New York reports that, by June 15, ICE reported that 2,059 detainees had tested positive for the COVID-19 virus and that the virus had spread to sixty-one facilities. The distinction between internment camp and death camp becomes increasingly blurred.

One can only wonder how our manikin Christian leaders – Trump, in 2015: “I’m Protestant. I’m Presbyterian. I’m proud of it. I’m very proud of it” and, in 2020: “I am an Evangelical. I’m a Christian. I’m a Presbyterian”; and Pence: “’I’m a born-again evangelical Catholic” — manage to wrap their souls around Jesus’ injunction, as recorded in Matthew 19:14: “Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God.”

China’s internment or “re-education” camps, incarcerating more than a million Muslim Chinese, mainly Uighurs, are an industrialized and psychologically invasive iteration of the concentration camp idea, an idea that President Trump described as “exactly the right thing to do,” as recounted by Trump’s former national security adviser John Bolton in The Room Where It Happened.

It may also be worth pointing out that, while the American press raised the country’s fighting spirit to fever pitch with accounts of Spanish barbarities abroad, its reporting on horrific injustices within the borders of the United States — lynchings, for example — made no pretense of being objective. In June 11, 2018, New York Times opinion piece headlined “How Northern Newspapers Covered Lynchings,” Charles Seguin, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Arizona, observed: “In the late 1800s well into the 20th century, thousands of people, mostly black and poor, were murdered by lynch mobs …. Lurid details of supposed rapes of white women by black men, often entirely fabricated, were recounted in Southern papers to justify, or even to incite, lynchings….”

Many Northern papers were complicit, Seguin notes, pointing out that The New York Times ran the headline ‘A Brutal Negro Lynched’ eleven times between 1880 and 1891.

Dispatches from a lopsided war that broke out close to home sold newspapers; reporting on domestic horrors would have to wait, for decades. Meanwhile, America was engaged in what became its first colonial-era war when, in the Philippines, its enemy was a Filipino freedom fighter named Emilio Aguinaldo whose troops had all but conquered their overbearing Spanish rulers when the Americans arrived and took over.

The Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, formalized the takeover of the Philippines — along with Puerto Rico and Guam — by the United States, leaving Aguinaldo no choice but to take up arms against this new would-be colonial overlord. And so a new war began, between the First Philippine Republic and the United States. It began on February 4, 1899 and ended July 2, 1902, six weeks after Aguinaldo pledged his allegiance to the American government told his followers to lay down their weapons:

“Let the stream of blood cease to flow; let there be an end to tears and desolation.”

An estimated 1,500 Americans were killed in action, while nearly twice that number died of disease. For Filipinos the cost was far greater, with an estimated 20,000 combatants killed, and more than 200,000 civilians dying of violence, famine, and disease.

On October 14, 1899, eight months into the Filipino-American war, and nine years after the massacre by the US 7th Cavalry of more 300 Lakota Sioux men, women, and children at Wounded Knee, President William McKinley, who could legitimately call himself a wartime president, went on a thirteen-town tour of South Dakota.

The tour started in Aberdeen, where McKinley welcomed home the 1st South Dakota Infantry Regiment, which, under the leadership of General Arthur MacArthur, had served 126 consecutive days under fire and had suffered heavy casualties: twenty-seven killed in action against “the insurrectionist forces,” with ninety-three wounded. At his second stop, at Redfield, McKinley joked about the conflict. “We have been adding territory to the United States,” he said. “The little folks will have to get a new geography.” The line was rewarded with “Laughter and applause.”

A month later, back in the White House, McKinley addressed five clergymen representing the General Missionary Committee of the [Northern] Methodist Episcopal Church, who had come to Washington to attend a convention. The audience had risen and was preparing to leave when, according to notes taken by one of the attendees, the president called out: “Hold a moment longer!” And, indeed, the speech is worth listening to and hearing out.

“Before you go I would like to say just a word about the Philippine Business. I have been criticized a good deal about the Philippines, but don’t deserve it. The truth is I didn’t want the Philippines, and when they came to us, as a gift from the gods, I did not know what to do with them…. I thought first we would take only Manila; then Luzon; then other islands perhaps also. I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight; and I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night.

“And one night late it came to me this way. I don’t know how it was, but it came: (1) That we could not give them back to Spain — that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not turn them over to France and Germany, our commercial rivals in the Orient — that would be bad business and discreditable; (3) that we could not leave them to themselves — they were unfit for self-government and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain’s was; and (4) that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them [the Filipinos had been thoroughly evangelized long before the Americans arrived]; and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for who Christ also died.

“And then I went to bed, and went to sleep, and slept soundly, and the next morning I sent for the chief engineer of the War Department (our map-maker), and I told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United States (pointing to a large map on the wall of his office), and there they will stay while I am president.”

Perhaps only American presidents can get away with wrapping a battle for conquest in the swaddling clothes of Christianity. While the language of the speech may remind one of pious Mike Pence, the girth of the speaker — a short man who weighed 233 pounds — may remind one of Donald Trump — a six-footer who weighs 245 pounds. It is this heavyweight, now besieged by critics of his policies at home and his buddies abroad, who may be tempted to wrap himself in the Stars and Stripes and discover a pretext for going to war, simply by listening to his oracular gut, which, as he has boasted, “tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.”

Sidebar: from Mark Twain’s Essay, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” published in North American Review, February 1901:

On the 1st of May, [Admiral] Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet. This left the Archipelago in the hands of its proper and rightful owners, the Filipino nation. Their army numbered 30,000 men, and they were competent to whip out or starve out the little Spanish garrison; then the people could set up a government of their own devising.

Our traditions required that Dewey should now set up his warning sign, and go away. But the Master of the Game happened to think of another plan — the European plan. He acted upon it. This was, to send out an army — ostensibly to help the native patriots put the finishing touch upon their long and plucky struggle for independence, but really to take their land away from them and keep it. That is, in the interest of Progress and Civilization.

The plan developed, stage by stage, and quite satisfactorily. We entered into a military alliance with the trusting Filipinos, and they hemmed in Manila on the land side, and by their valuable help the place, with its garrison of 8,000 or 10,000 Spaniards, was captured — a thing which we could not have accomplished unaided at that time.

We got their help by — by ingenuity. We knew they were fighting for their independence, and that they had been at it for two years. We knew they supposed that we also were fighting in their worthy cause — just as we had helped the Cubans fight for Cuban independence — and we allowed them to go on thinking so. Until Manila was ours and we could get along without them. Then we showed our hand.

Jon Swan is the author of two collections of poems — Journeys and Return and A Door to the Forest. His poems have been published in several magazines and reviews in the United States and the United Kingdom. In collaboration with director Ulu Grosbard, he translated Peter Weiss’s Die Ermittlung (The Investigation), and, in collaboration with Carl Weber, Weiss’s Hoelderlin. He lives in Yarmouth, Maine, with his wife, Marianne.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.