Is Green Hydrogen the Sustainable Fuel of the Future?

Vanora Bennett / European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

(June 22, 2020) — Imagine a clean alternative to fossil fuels, one that leaves no greenhouse gas residues and even, unlike solar and wind renewables, can be used at any moment of the day or night, whatever the weather conditions.

Imagine that using it instead of fossil fuels sharply reins in the harmful emissions raising global temperatures, helping the world to solve the climate crisis.

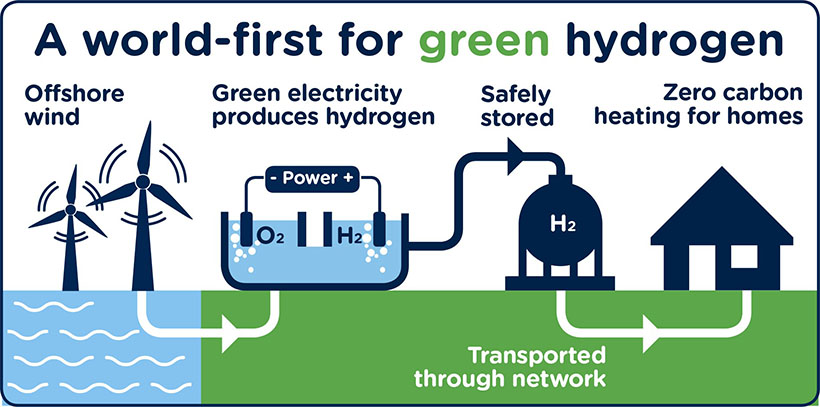

This is not a fairy story. This gas exists. It’s called green hydrogen, and is made by using clean electricity from renewable energy technologies to electrolyse water (H2O), separating the hydrogen atom within it from its molecular twin oxygen.

The catch has always been that the cost of making green hydrogen prices it out of competition with fossil fuels, because, even if it is carbon-free, it is energy-intensive. But that is changing, because, for the past two years, improvements in renewable energy technology have seen renewable electricity costs plummet.

Now, as the world plans economic recovery efforts after the coronavirus pandemic, and trillions of dollars and euro are readied to invest in build-back-better approaches, an increasing number of scientists and policymakers are saying green hydrogen’s time has come to be brought fully into the energy mix of the future.

They’re advocating investing in stimulating production, both to tackle the economic fallout of this year’s pandemic and to build a future without fear of climate cataclysm.

“Important emerging elements of clean energy progress – hydrogen electrolysers and lithium-ion batteries – are on the verge of becoming the decade’s breakout technologies. These technologies should play a key role in bolstering Europe’s transport and industry as the continent emerges from the crisis and looks to develop new advanced manufacturing for export,” the International Energy Agency’s executive director Fatih Birol and Frans Timmermans, executive vice-president of the European Commission, wrote in May.

“If the EU seizes this opportunity, it will give itself a cutting edge on global markets,” Birol and Timmerman concluded.

Their editorial – as well as reported comments by Birol that green hydrogen technology was “ready for the big time” and that governments should channel investments into the field — came as the European Union prepared to publish its own hydrogen strategy while implementing the European Green Deal plan to reduce net emissions to zero by 2050.

The pace of discussion on green hydrogen has picked up, especially since the outbreak of coronavirus.

Governments including those of Germany, Britain, Australia and Japan are working on or have announced hydrogen strategies. Australia has set aside A$300 million ($191 million) to jumpstart hydrogen projects. Portugal plans a new solar-powered hydrogen plant which will produce hydrogen by electrolysis by 2023. The Netherlands unveiled a hydrogen strategy in late March, outlining plans for 500 megawatts (MW) of green electrolyser capacity by 2025.

“We could use these circumstances, where loads of public money are going to be needed into the energy system, to jump forward towards a hydrogen economy,” said Diederik Samsom, who heads the European Commission’s climate cabinet. This could result in hydrogen use scaling up faster than was expected before the pandemic, he was quoted by Reuters as saying.

Most of the hydrogen produced today is not green. The gas is colour-coded according to the way it is produced, says the EBRD’s Christian Carraretto.

“The hydrogen that the world uses today is made from either coal or natural gas. This hydrogen is carbon-intensive, it’s not a green fuel. It’s called grey hydrogen if it comes from gas, while the hydrogen produced from coal is called black. Then there is blue hydrogen, an upgrade of the grey, where the CO2 emitted is captured upstream, so the system doesn’t emit CO2 in the atmosphere.”

The European Commission has earmarked clean hydrogen — a loose term which can include gas-based hydrogen, if fitted with technology to capture the resulting emissions, as well as green hydrogen — as a “priority area” for industry in its Green Deal.

If clean hydrogen does start to play a bigger part in the world’s energy mix, incorporating it will be technically relatively easy, Mr Carraretto said, as the infrastructure already built to carry natural gas can also carry hydrogen.

He said a recent study had shown 70 per cent of Italy’s gas network would be hydrogen-ready if there were enough hydrogen being produced to be carried down its pipes. It could be used in both homes and industry without radical change.

“Clean hydrogen is what the EU think is the solution to deliver on decarbonised fuels. And the reason why it’s important is that not all economic activities can move to renewables only. There are some sectors that are typically hard to decarbonise — sectors like steel, or chemical industries, or to some extent aviation — which will still use fuels in their systems.

“So either they are stuck with the cleanest of the fossil fuels or they switch to decarbonised fuels like hydrogen or biogas. Biogas is a mainstream technology and it hasn’t really picked up a lot because there is an issue with availability of organic wastes. So hydrogen is what we see as the most promising option at this moment.”

There remains the question of prices. Today, hydrogen made from fossil fuels costs between $1-$1.8/kg. Green hydrogen can cost around $3-$6/kg, making it significantly more expensive than the fossil fuel alternatives.

However, increased demand could reduce the cost of electrolysis. Coupled with falling renewable energy costs, green hydrogen could fall to $1.5/kg by 2050 and possibly sub-$1/kg, making it competitive with natural gas. Higher carbon prices would also encourage the shift.

Mr Carraretto said: “Here we are probably in the same situation as we were a decade or two ago with renewable energy, where this solution is still more expensive than the alternatives. But even today it’s only two or three times more expensive, it’s not 100 times more expensive, so if things keep going and if there is policy push going forward, our expectation that it will become really cost-competitive soon.

“And that’s why we see a lot of big players looking at it, pilot projects happening everywhere.”

“What is also exciting is that with the recent dramatic fall in renewable energy prices — particularly in the southern and eastern Mediterranean countries where we work, and potentially with offshore wind being developed in countries from Turkey to Poland and Greece, too — these countries could become sources of production of green hydrogen, with projects we could consider investing in, within a few years,” Mr Carraretto added. “This is really on the edge of becoming a game-changer”.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.