Our Long, Forgotten History of Election-Related Violence

Jelani Cobb / The New Yorker

(September 6, 2020) — In the fall of 1856, according to news reports, a Baltimore resident named Charles Brown was “peaceably walking along the street” when he was shot dead.

It was a local Election Day, and Brown was in the vicinity of a Twelfth Ward polling place. Democrats attempting to enter it had been repelled by supporters of the American Party, better known as the Know-Nothings. For some two hours, the groups exchanged gunfire in what the Baltimore American described as “guerrilla warfare.”

Brown was one of five people killed, and the newspaper marveled that more lives were not lost. This was not an uncommon event. The American Party, a group defined by its truculent nativism, frequently deployed violence to political ends, particularly against immigrant voters. As Richard Hofstadter and Michael Wallace, in their book “American Violence: A Documentary History,” wrote of Baltimore, “In many districts, immigrants were stopped from voting entirely.”

Riots broke out in Philadelphia after Nativists burned down a Catholic church in May 1844. This lithograph shows the Know-nothings (in the top hats) clashing with the state militia.

The United States is considered one of the most stable democracies in the world, but it has a long, mostly forgotten history of election-related violence. In 1834, during clashes between Whigs and Democrats in Philadelphia, an entire city block was burned to the ground.

In 1874, more than 5,000 men fought in the streets of New Orleans, in a battle between supporters of Louisiana’s Republican governor, William Kellogg, and of the White League, a group allied with the Democrats. And the nation’s record of overlooking the violent prevention of Black suffrage is much longer than its record of protecting Black voters.

The general public tends to view such calamities as a static record of the past, but historians tend to look at them the way that meteorologists look at hurricanes: as a predictable outcome when a number of recognizable variables align in familiar ways. In the aftermath of events in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and Portland, Oregon, we are in hurricane season.

Following the release, on August 23rd, of a video showing Officer Rusten Sheskey shooting Jacob Blake, an unarmed twenty-nine-year-old Black man, seven times in the back, protesters poured into the streets of Kenosha. Some of them engaged in looting, and, two nights later, Kyle Rittenhouse, a seventeen-year-old with an AR-15-style rifle, reportedly crossed state lines, from Illinois, to defend property in the city.

According to prosecutors, he shot three protesters, two of them fatally. Several nights later, a caravan of Trump supporters drove through downtown Portland, where anti-police-brutality protesters have been gathering for months, and fired paintballs and pepper spray into the crowd. Aaron J. Danielson, a supporter of the right-wing group Patriot Prayer, was shot dead; the suspect, Michael Reinoehl, an Antifa supporter, was fatally shot by law-enforcement officers last Thursday, as they attempted to apprehend him south of Seattle.

Throughout these horrendous developments, Donald Trump has been at cross-purposes with the calling of his office. He has sown conflict where none existed and exacerbated it where it did.

On a visit to Kenosha, Trump did not mention Blake, who has been left partially paralyzed. But he has said that Rittenhouse, who has been charged with homicide, was likely acting in self-defense, claiming — without offering any evidence, as is the President’s habit — that Rittenhouse “probably would’ve been killed by protesters.”

In 2013, when President Obama spoke about Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black seventeen-year-old who was shot to death in Sanford, Florida, he addressed racism but not the particulars of the case, so as to not interfere with legal proceedings. Republicans were nevertheless quick to accuse Obama of impropriety. Seven years later, Party leaders have made no such complaints about Trump’s advocating for Rittenhouse.

The Trump Presidency has been an escalating series of insults, each enabling greater violations of norms, ethics, and laws. That pattern now seems poised to upend democracy itself. It began even before Trump took office, when he refused to release his tax returns; claimed that his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton, should be in jail; and openly enlisted a foreign adversary to help achieve that end.

This year, he has removed five inspectors general from their posts and, with the assistance of Attorney General William Barr, corrupted the Department of Justice to such a degree that we are now unsure of the legal meaning of the word “guilty” when applied to a Trump-connected defendant.

The likelihood of political violence was also apparent from the start. Trump’s 2016 rallies tipped over into displays of aggression directed at the media and at those who opposed him.

Trump supporter Cesar Sayoc mailed letter bombs to Obama and 14 other Demorcrats

Such is the chaos of today that we’ve nearly forgotten that, two years ago, Cesar Sayoc mailed pipe bombs to Obama, Clinton, and 14 others he believed had treated Trump unfairly. Sayoc pleaded guilty; his lawyers described him as “a Donald Trump super-fan” who suffered from mental illness, leaving him vulnerable to the antagonisms of the political climate.

The twenty-one-year-old Patrick Crusius was charged with fatally shooting 23 people in El Paso last year. The language of an anti-immigrant manifesto he allegedly posted before the shooting was noted for its echoes of Trump’s rationalizations for building his border wall. (Crusius pleaded not guilty.)

This May, the Michigan legislature temporarily shut down, after armed militia members entered the capitol to protest the state’s stay-at-home order. A couple of weeks earlier, Trump had tweeted, “LIBERATE MICHIGAN!”

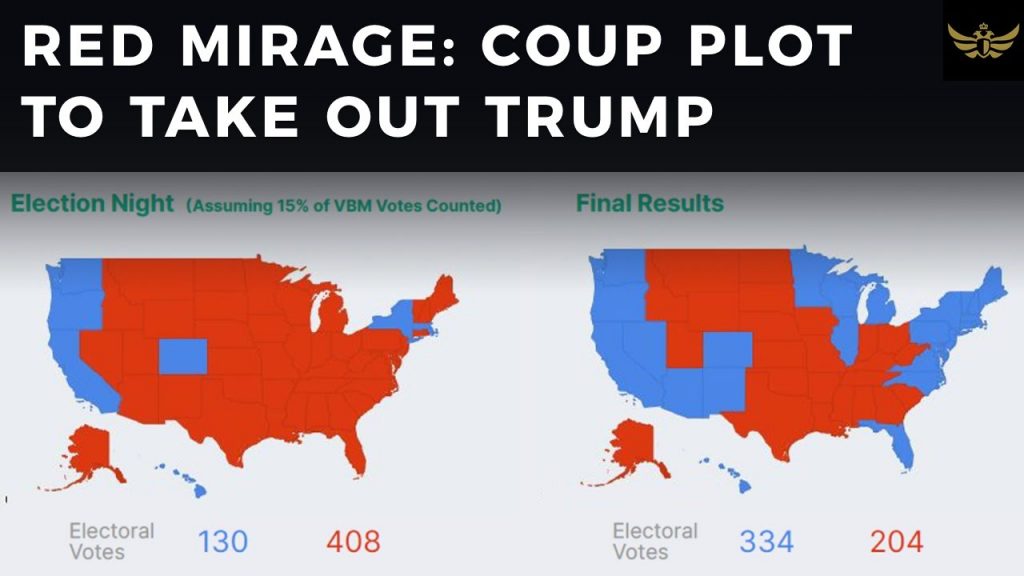

The Transition Integrity Project , a nonpartisan group of academics, journalists, and current and former government and party officials, recently released a report outlining a number of election scenarios that are both plausible and terrifying. Trump has primed his followers with repeated warnings of voter fraud, so there is a real possibility that they may denounce as illegitimate any outcome in which he loses.

Beyond that, the report suggests, the Administration could seize mail-in ballots in order to prevent them from being counted, or pressure Republican-controlled legislatures to certify results before all mail-in ballots have arrived. The authors conclude that “voting fraud is virtually non-existent, but Trump lies about it to create a narrative designed to politically mobilize his base and to create the basis for contesting the results should he lose. The potential for violent conflict is high, particularly since Trump encourages his supporters to take up arms.”

This is where we are — at the perilous logical extension of all that Trump represents. A weather forecast is not a prediction of the inevitable. We are not doomed to witness a catastrophic tempest this fall, but anyone who is paying attention knows that the winds have begun to pick up.

What’s The Worst That Could Happen?

The election will likely spark violence — and a constitutional crisis

Rosa Brooks / The Washington Post

(September 3, 2020) — We wanted to know: What’s the worst thing that could happen to our country during the presidential election? President Trump has broken countless norms and ignored countless laws during his time in office, and while my colleagues and I at the Transition Integrity Project didn’t want to lie awake at night contemplating the ways the American experiment could fail, we realized that identifying the most serious risks to our democracy might be the best way to avert a November disaster.

So we built a series of war games, sought out some of the most accomplished Republicans, Democrats, civil servants, media experts, pollsters and strategists around, and asked them to imagine what they’d do in a range of election and transition scenarios.

A landslide for Joe Biden resulted in a relatively orderly transfer of power. Every other scenario we looked at involved street-level violence and political crisis.

Picture this:

On the morning of Election Day, false stories appear online claiming that Biden has been hospitalized with a life-threatening heart attack and the election has been delayed. Every mainstream news organization reports that the rumors are unfounded, but many Biden supporters, confused by the bogus claims, stay home.

Still, by late that night, most major networks have called the election for Biden: The former vice president has won key states and has a slender lead in the national popular vote, and polling experts predict that his lead will grow substantially as Western states count an unusually high number of mail-in ballots. The electoral college looks secure for Biden, too.

But Trump refuses to concede, alleging on Twitter that “MILLIONS of illegal ALIENS and DEAD PEOPLE” have voted in large numbers and that the uncounted ballots are all “FAKE VOTES!!!” Social media fills with posts from Trump supporters alleging that the election has been “stolen” in a “Deep State coup,” and Trump-friendly pundits on Fox News and OAN echo the message.

Soon, Attorney General William P. Barr opens an investigation into unsubstantiated allegations of massive vote-by-mail fraud and ties between Democratic officials and antifa. In Michigan and Wisconsin, where Biden has won the official vote and Democratic governors have certified slates of pro-Biden electors, the Trump campaign persuades Republican-controlled legislatures to send rival pro-Trump slates to Congress for the electoral college vote.

The next week is chaotic: A list of Michigan and Wisconsin electors for Biden circulates on right-wing social media, including photos, home addresses and false claims that scores of them are in the pay of billionaire George Soros or have been linked to child sex-trafficking rings.

Massive pro-Biden street protests begin, demanding that Trump concede. The president tweets that “REAL PATRIOTS MUST SHOW THESE ANTIFA TERRORISTS THAT CITIZENS WHO LOVE THE 2ND AMENDMENT WILL NEVER LET THEM STEAL THIS ELECTION!!!” Around the nation, violent clashes erupt. Several people are injured and killed in multiple incidents, though reports conflict about their identities and who started the violence.

Meanwhile, Trump declares that “UNLESS THIS CARNAGE ENDS NOW,” he will invoke the Insurrection Act and send “Our INCREDIBLY POWERFUL MILITARY and their OMINOUS WEAPONS” into the streets to “Teach these ANTI-AMERICAN TERRORISTS A LESSON.” At the Pentagon, the Joint Chiefs of Staff convene a hurried meeting to discuss the crisis.

And it’s not even Thanksgiving yet.

That dystopia is based on how events played out in one of the Transition Integrity Project’s exercises. We explored the four scenarios experts consider most likely: a narrow Biden win; a big Biden win, with a decisive lead in both the electoral college and the popular vote; a Trump win with an electoral college lead but a large popular-vote loss, as in 2016; and finally, a period of extended uncertainty as we saw in the 2000 election.

[The loser of November’s election may not concede. Their voters won’t, either.]

With the exception of the “big Biden win” scenario, each of our exercises reached the brink of catastrophe, with massive disinformation campaigns, violence in the streets and a constitutional impasse. In two scenarios (“Trump win” and “extended uncertainty”) there was still no agreement on the winner by Inauguration Day, and no consensus on which candidate should be assumed to have the ability to issue binding commands to the military or receive the nuclear codes. In the “narrow Biden win” scenario, Trump refused to leave office and was ultimately escorted out by the Secret Service — but only after pardoning himself and his family and burning incriminating documents.

For obvious reasons, we couldn’t ask Trump or Biden — or their campaign aides — to play themselves in these exercises, so we did the next best thing: We recruited participants with similar backgrounds. On the GOP side, our “players” included former Republican National Committee chairman Michael Steele, conservative commentator Bill Kristol and former Kentucky secretary of state Trey Grayson.

On the Democratic side, participants included John Podesta, chair of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign and a top White House adviser to Bill Clinton and Barack Obama; Donna Brazile, the campaign chair for Al Gore’s 2000 presidential run; and Jennifer Granholm, former governor of Michigan. Other participants included political strategists, journalists, polling experts, tech and social media experts, and former career officials from the intelligence community, the Justice Department, the military and the Department of Homeland Security.

In each scenario, Team Trump — the players assigned to simulate the Trump campaign and its elected and appointed allies — was ruthless and unconstrained right out of the gate, and Team Biden struggled to get out of reaction mode. In one exercise, for instance, Team Trump’s repeated allegations of fraudulent mail-in ballots led National Guard troop to destroy thousands of ballots in Democratic-leaning ZIP codes, to applause on social media from Trump supporters. Over and over, Team Biden urged calm, national unity and a fair vote count, while Team Trump issued barely disguised calls for violence and intimidationagainst ballot-counting officials and Biden electors.

[I was on Trump’s voter fraud commission. I sued it to find out what it was doing.]

In every exercise, both teams sought to mobilize their supporters to take to the streets. Team Biden repeatedly called for peaceful protests, while Team Trump encouraged provocateurs to incite violence, then used the resulting chaos to justify sending federalized Guard units or active-duty military personnel into American cities to “restore order,” leading to still more violence. (The exercises underscored the tremendous power enjoyed by an incumbent president: Biden can call a news conference, but Trump can call in the 82nd Airborne.)

Similarly, Team Trump repeatedly attempted to exploit ambiguities and gaps in the legal framework. (There are more than you might think.) Team Trump repeatedly sought, for instance, to persuade state GOP allies to send rival slates of electors to Congress when the popular vote didn’t go its way. With competing slates heading to Washington for the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress that formally counts the electoral votes, Trump supporters argued that Vice President Pence, in his capacity as president of the Senate, had the power to decide which electors to recognize.

In contrast, Democrats argued that the House of Representatives had the constitutional authority to choose which electors should be accepted in the event of a deadlock — or, alternatively, the ability to prevent the joint session from taking place at all. (We didn’t resolve this kind of standoff in our exercises; it’s not clear how such a stalemate would be settled in real life.)

[Trump is wrong. Concession speeches aren’t binding at all.]

In the “Trump win” scenario, desperate Democrats — stunned by yet another election won by the candidate with fewer votes after credible claims of foreign interference and voter suppression — also sought to send rival slates of electors to Congress. They even floated the idea of encouraging secessionist movements in California and the Pacific Northwest unless GOP congressional leaders agreed to a series of reforms, including the division of California into five smaller states to ensure better Senate representation of its vast population, and statehood for D.C. and Puerto Rico.

While both parties appealed to the courts as well as to public opinion, the legal experts in our exercises pointed out that the judicial system might well avoid rendering decisions on the central issues, since courts might see them as fundamentally political, rather than judicial, in nature. Other players noted that there was, in any case, no guarantee that the losing side would accept a ruling from a highly politicized Supreme Court.

But there’s some good news: This kind of exercise doesn’t predict the future. In fact, war-gaming seeks to forecast all the things that could go wrong — precisely to prevent them from happening in real life. And if the Transition Integrity Project’s exercises highlighted various bleak possibilities, they also suggested some ways we might, as a nation, avoid democratic collapse.

First and foremost, congressional and state leaders, including legislators, governors, state secretaries of state and state attorneys general from both parties, can commit to protecting the integrity of the electoral process against partisan meddling. State officials can ensure that voters have detailed, accurate and timely information about where, when and how to vote, and make sure they understand that nobody can cancel or postpone the election.

State officials can also eliminate administrative hurdles that may prevent voters from meeting mail-in ballot deadlines through no fault of their own, and recruit enough poll workers to ensure that all voters can vote and all ballots can be counted. Finally, they can take steps to protect the election officials who manage vote counting from harassment and intimidation attempts, and establish — in advance and on a bipartisan basis — standards for adjudicating any competing claims about how to allocate a state’s electoral votes.

[Trump’s bogus attacks on mail-in voting could hurt his supporters, too]

Meanwhile, military and law enforcement leaders can prepare for the possibility that politicians will seek to manipulate or misuse their coercive powers. Partisans, including Trump, may try to deploy law enforcement, National Guard troops and, potentially, active-duty military personnel to “restore order” in a manner that primarily benefits one party, or involve troops and law enforcement in efforts to interrupt the ballot-counting process.

The federal response to this summer’s protests in D.C.’s Lafayette Square and Portland, Ore., suggests that this is not purely speculative. To avoid becoming unwitting pawns in a partisan battle, military and law enforcement leaders can issue clear advance statements about what they will and won’t do. They can train troops and police officers on de-escalation techniques and on the vital need to remain nonpartisan and respectful of civil liberties.

The media also has an important role. Responsible outlets can help educate the public about the possibility — indeed, the likelihood — that there won’t be a clear winner on election night because an accurate count may take weeks, given the large number of mail-in ballots expected in this unprecedented mid-pandemic election.

Journalists can also help people understand that voter fraud is extraordinarily rare, and, in particular, that there’s nothing nefarious about voting by mail. Social media platforms can commit to protecting the democratic process, by rapidly removing or correcting false statements spread by foreign or domestic disinformation campaigns and by ensuring that their platforms aren’t used to incite or plan violence.

Finally, ordinary citizens can help, too — perhaps most of all. As the jurist Learned Hand said in 1944, “Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it . . . while it lies there, it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.” This is as true now as it was then: When people unite to demand democracy and the rule of law, even repressive regimes can be stopped in their tracks. Mass mobilization is no guarantee that our democracy will survive — but if things go as badly as our exercises suggest they might, a sustained, nonviolent protest movement may be America’s best and final hope.

Rose Brooks a law professor at Georgetown University and co-founder of the Transition Integrity Project.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.