Mexico’s Water Crisis Heats Up as Transfer to US Looms

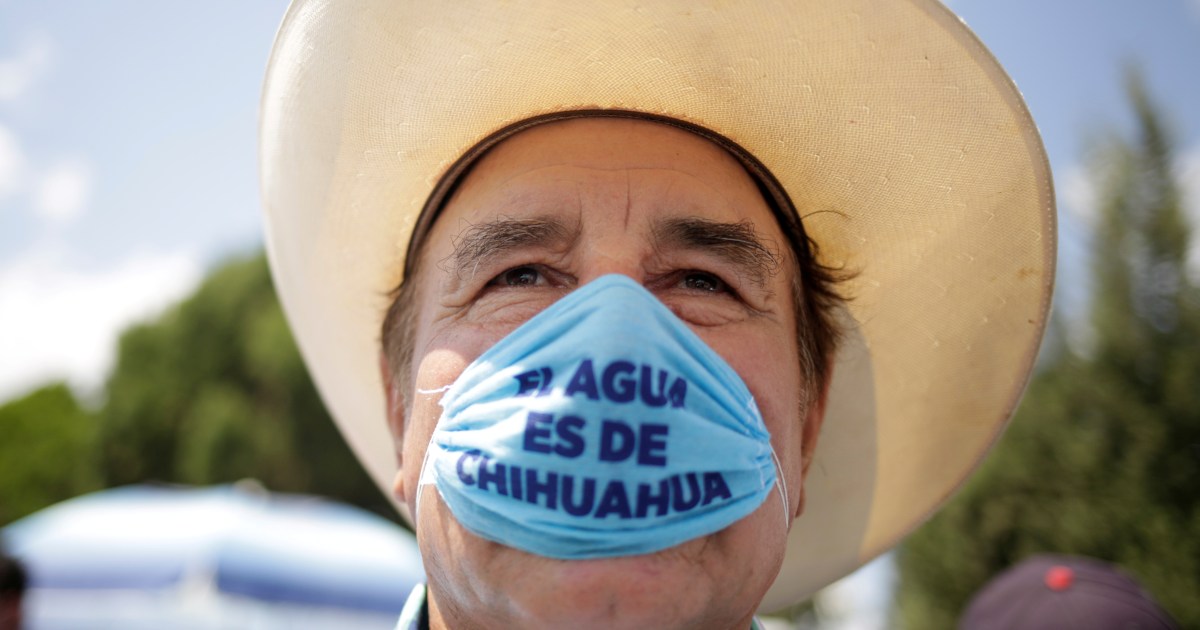

Farmers in Mexico’s drought-hit Chihuahua state say a large-scale water transfer to the US threatens their livelihoods.

Eoin Wilson / Al Jazeera

MEXICO CITY (October 8, 2020) — Carrying sticks and stones, thousands of farmers descended on La Boquilla dam in Mexico’s northern state of Chihuahua in early September to voice their anger over a looming transfer of millions of cubic metres of water to the United States.

Waiting for them at the site on the Rio Conchos River on September 8 was a group of several hundred National Guard troops, who quickly abandoned their posts. Farmers turned off the valves, and weeks later, they remain at La Boquilla — demanding the transfer be cancelled.

The scene highlights a long-brewing conflict between Mexico’s federal government and local farmers over the water transfer, which is mandated under a 1944 treaty between Mexico and its northern neighbour.

The farmers, hard hit by drought, say the transfer would leave them unable to sustain their livelihoods, and the conflict has worsened tensions between the state and federal government in Mexico over the source of dwindling water resources.

“The root of the problem is the misuse, mismanagement and distribution of water by Conagua,” said Salvador Alcantar, president of the Association of Irrigation Users of the State of Chihuahua (Aurech), referring to Mexico’s federal water regulator.

There has been a lack of transparency, Alcantar told Al Jazeera, and roundtable discussions between the various stakeholders have floundered. Aurech members were among the protesters who occupied La Boquilla (“The Nozzle”) last month.

“Not being able to demonstrate technically or legally what they were doing, they [Conagua] decided to use force,” Alcantar said about the crackdown on protesters.

Members of the Mexican National Guard patrol as farmers take part in a protest against the decision to divert water from La Boquilla dam to the US

Brewing Tensions

The water transfers between Mexico and the US are governed by a 1944 treaty to ensure the mutually beneficial use of water in agricultural areas on both sides of the border. Under the agreement, Mexico receives from the US four times the amount of water it sends north.

More specifically, the US sends approximately 1,185 million cubic metres (MCM) to Mexico each year, according to Mexican government figures, while Mexico is required to send 431 million cubic metres to the US annually.

Most of that water comes from the state of Chihuahua’s Rio Conchos, the main tributary of the Rio Bravo, which starts in the Sierra de Chihuahua. Known as the Rio Grande in the US, the Rio Bravo begins in Colorado and flows into the Gulf of Mexico, for long stretches forming a natural border between Mexico and the US.

But the treaty allows Mexico to make its transfers over five years — a safeguard against unpredictable rainfall, or other conditions — meaning that it can deliver its total of 2,155 MCM at any point over that period.

Mexico now owes the US 426 MCM of water, and it must transfer that total amount by October 24.

“Chihuahua has to [provide] 54 percent [of that amount], because the principal river which contributes to the Rio Bravo is the Rio Conchos,” explained Víctor Quintana, a social activist, writer and sociologist, and member of the Morena party of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

“It’s an agreement which is advantageous for Mexico, but disadvantageous for Chihuahua,” he said.

The 1944 treaty is overseen by the International Boundary and Water Commission, jointly comprised of the US Department of State and the Mexican Secretariat of Foreign Relations.

As the federal government body responsible for water throughout the country, the National Water Commission, Conagua, has been the focus of consistent criticism and the target of farmers’ anger. Several times over the last months Conagua vehicles have been set alight.

The agency has repeatedly rejected claims it has acted inappropriately. The group’s general coordinator of communications, Jose Luis Juarez, told Mexican investigative journalism outlet Contralinea last month that Conagua “categorically rejects” the allegation “that corruption practices are tolerated”.

Still, tensions between farmers and the federal government are exacerbated by a severe drought in Chihuahua, where the state government called on federal authorities to declare a natural disaster due to drought in 52 of the state’s municipalities.

Farmers, among other people, protest in Delicias, Chihuahua state against the decision to divert water from La Boquilla dam

Illegal Extraction, Weak Infrastructure

The water crisis in Chihuahua is fuelled by two main issues, according to investigative journalist Ignacio Alvarado, who is from Chihuahua and has investigated conflicts tied to natural resources: the illegal extraction of water and the rudimentary infrastructure of dams and canals.

The scarcity of water in Chihuahua has made it a lucrative source of income for many, explained Alvarado, adding that, apart from organised crime, the extraction of “water is possibly, more so than the extraction of minerals, the detonator of most violence in the state”.

Quintana, also an expert on the politics of water, argues that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is also a factor in the state’s water crisis, affecting rural Chihuahua and its dry, arid climate, and making it more difficult for local farmers to remain competitive in the US.

The Chihuahuan desert, which runs from the US state of Colorado to the central Mexican highlands, has faced increasing challenges in recent years, especially related to the Rio Bravo’s water levels. “Climate change and over-extraction threaten the river’s future, and all who depend on it,” a 2015 World Wildlife Fund report warned.

The situation is also exacerbated by severe overexploitation of wells and aquifers, Jeffrey Jones, a former senator for Chihuahua for the National Action Party (PAN), explained. “There continue to be more and more wells extended across areas where the [extraction] rights have been overextended,” he said.

“The overexploitation of wells is an extremely grave problem.”

Political Front

The water conflict turned deadly on September 8, the same night that clashes took place between National Guard troops and farmers at the dam. The National Guard has been accused of killing a protester, Yesica Silva, and seriously injuring her husband in the town of Delicias.

The agency said the death occurred after its officers “repelled aggression” and Mexico’s president has called for an investigation into whether Silva was killed by the National Guard, Reuters reported.

The dispute also has increasingly shifted into the political realm, with some arguing that the dispute is being used by right-wing parties to attack the government of Lopez Obrador ahead of state elections next year.

Quintana said that while the farmers’ protests are legitimate, “groups tied to National Action [PAN], including from Frena [the National Anti-AMLO front]” are increasingly getting involved in the conflict, and could help create a front against Lopez Obrador.

Frena — a self-described citizens’ movement — is pushing for Lopez Obrador’s resignation. On September 23, the group set up a protest camp in Mexico City’s main Zocalo plaza to demand the president step down.

Former PAN president, Felipe Calderon, has pledged his solidarity to the organisation, though Frena has publicly distanced itself from political parties.

Alcantar, the Aurech president, acknowledged that some farmers and farmers’ organisations have made tactical alliances with politicians and political parties, such as the PAN, as a way to put pressure on the federal government to commit to a dialogue.

He stressed, however, that “we are united, but not in each others’ pockets”.

In a move that some speculated was an attempt to divide opposition to the federal government, a “dialogue table” was agreed on between the federal government and mayors from 10 Chihuahua municipalities on September 21.

The 10 mayors, however, were all from the PRI. Notably absent was the PAN governor of Chihuahua, Javier Corral.

In a sign of the deepening acrimony between the Lopez Obrador government in Mexico City and Chihuahua’s state government, Corral accused the federal government of withdrawing the security cooperation of the army and federal police in the state.

He wrote on Twitter that the move was retribution for the situation at La Boquilla.

US-Mexico Relations

People hold placards to remember a protester, Yesica Silva, who was killed on September 8 (Jose Luis Gonzalez/Reuters)

Meanwhile, on September 24, Lopez Obrador announced a “cleansing” of Conagua, saying the state had been “taken over” by the PAN. He also warned that it was “very irresponsible” to put Mexico’s relationship with the US at risk for the sake of “wanting to win an election in a state”.

Local media recently reported that the Mexican government is negotiating with the US to try to find a way of meeting its contractual obligations by taking water from other dams.

The US presidential election is just over a week after the treaty deadline of October 24 and Lopez Obrador is highly unlikely to allow the potentially negative consequences of a missed water transfer.

While US President Donald Trump has not weighed in on the current water crisis in Chihuahua, Texas Governor Greg Abbott on September 15 wrote to US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo asking for his assistance to guarantee Mexico’s compliance.

With a continuing drought, Chihuahua state elections next year and a political climate that is increasingly polarised in both Mexico and the US, the fallout from Chihuahua’s water crisis could be significant.

“There needs to be dialogue,” Jones told Al Jazeera, “but it should have been started a long time before now.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.