We’re due for a major foreign policy realignment in Washington and a new president could make it happen.

Daniel R. Pepetris / The American Conservative

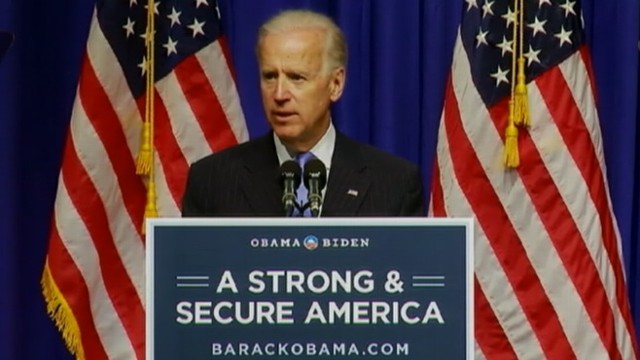

(November 6, 2020) — Barring a last-minute, groundbreaking shift in the vote tally, it looks like former vice president Joe Biden will be the 46th president of the United States. What this development means for foreign policy, however, is not yet clear.

While there have been a number of predictions made about what foreign policy will look like under a Biden administration, none of us can say with any certainty how US grand strategy will evolve — if it does at all. As the next administration gets seated, stakeholders will offer recommendations on what challenges should tackled as urgent priorities. Others, who may serve in national security roles next year, will be tempted to avoid rocking the boat and be largely content with making small refinements at the margins. Liberal hegemony and interventionism, the engine of US grand strategy since the end of the Cold War, will undoubtedly have plenty of support.

What the United States needs instead is a foreign policy doctrine of restraint — an underutilized playbook that would enhance our national security at a far less grandiose price tag.

Staying between the 48-yard lines may be the foreign policy establishment’s comfort zone. But for the rest of the country it hasn’t led to any considerable gains. If anything, the overall economic and military power of the US has weakened as a result of excessive military adventurism and an inability (or unwillingness) to distinguish what America really needs and what it can live without. Restraint would finally force policymakers to actually set priorities and realistic goals, throwing out expensive, counterproductive interventions in the process. Just as important, restraint would base US foreign policy choices on reality rather than idealistic ambition.

Whether the 2020 presidential election is the beginning of a broader realignment in how the US operates in the world is still very much an open question. Much of it will depend on the incoming administration’s personnel choices across the national security bureaucracy. However, there is no question that such a realignment is absolutely necessary, given the misjudgment, waste, and painful sacrifice that have defined US foreign policy over the last 20 years.

There is no region of the world where the United States would not benefit from putting pragmatism above reflexive interventionism.

Tens of thousands of American troops remain stationed in Europe, one of the most prosperous and peaceful continents on the planet. In the Middle East, the US military remains tied down in some of the region’s most intractable civil wars — despite Washington having little to no direct stake in any of the outcomes. All of this comes as support for ending US involvement in those very same wars grows ever higher among the American public.

Meanwhile, US policy on China is dangerously close to containment, a strategy that courts long-term confrontation with the world’s second-largest economic power. US-Russia relations are becoming increasingly adversarial — so much so that a regular phone call between the presidents of both nations can engender suspicion and controversy.

The end results of American primacy are clear: a fat $750 billion national security budget that is totally unnecessary for keeping the US safe; a $27 trillion national debt that shows no signs of stabilizing; a simultaneous series of near-permenant training, advising, and assisting missions in dozens of countries across three continents; military action and/or large-scale intervention in at least eight nations; two fruitless occupations in Afghanistan and Iraq; a small-scale but risky policing mission in Eastern Syria; and a rising China that has strengthened its own position by taking advantage of Washington’s numerous foreign policy foibles.

If a Biden administration wants to right the foreign policy ship, it should embrace more humble objectives, eliminate policies like maximum pressure on Iran that fail to accomplish anything outside of creating tension, and withdraw the military from a Middle East that is not as vital to US security and prosperity as it was decades ago.

In Europe, the US should ditch the redundant European Deterrence Initiative and stop deploying American forces to NATO’s eastern flank. Adding more members to NATO should no longer be US policy. NATO expansion, especially to nations like Ukraine and Georgia, worsens tensions with a nuclear-armed Russia, stretches the territory NATO needs to defend, and piles more security commitments on Washington’s shoulders.

China’s assertive behavior in Asia is a concern. But confronting China everywhere won’t tame Beijing’s conduct and may in fact do the opposite. A declaration of “strategic clarity,” where the US offers Taiwan a defense commitment in the vein of a formal treaty ally, is more likely to accelerate a possible Chinese invasion of the island than restrain Beijing from acting aggressively.

Preserving open lines of communication with China, competing with the Chinese responsibly in the economic realm, and providing allies and partners like Japan, Taiwan, and India with the ability to defend their own sovereignty from Chinese predations is a more effective (and less risky) strategy than deploying the military as the first line of defense.

Will any of these sensible foreign policy reforms come to pass? With the US election process still not over, it is premature to say one way or the other. But regardless of the final victor, the Washington foreign policy establishment has a lot of work ahead of it. Here’s to hoping the new administration doesn’t squander this opportunity.

Daniel R. DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.