The Electoral College — an undemocratic mess.

Minority Rule Cannot Last in America. It Never Has

Kenneth Owen / The Atlantic

(December 2, 2020) — Minority rule is fast becoming the defining feature of the American republic. In 2000 and 2016, presidential candidates who received fewer votes than their opponents were nevertheless sent to the White House. Joe Biden’s 2020 victory came not because he won nearly 7 million more votes nationally than President Donald Trump, but rather because he won about 200,000 votes more in a handful of swing states.

Congress has seen a similar dynamic: Though Republican senators make up the majority in the chamber, they represent more than 20 million fewer Americans than Democratic senators do. Such lopsided electoral calculus seems to fly in the face of both parties’ principles. It cannot last.

Though this period of minority rule is new since World War II, it is far from unprecedented. Unequal legislative apportionment has been a recurring quality of American government since its establishment. Parties who have found themselves in power by institutional oddities rather than overall weight of vote have refused to reach across the aisle, instead using their institutional advantage to further consolidate their hold on power.

Although such tactics have been successful in the short term, they have ultimately been only temporary expedients. When the minority parties were finally removed from power, the backlash against them was swift and strong.

Begin at the nation’s founding. At the time when American colonists started actively considering independence from Britain, Pennsylvania’s legislature no longer proportionally represented its population. The Pennsylvania Assembly had proved efficient and professional throughout the 18th century, defending the interests of the colonial population against British imperial officials, but as the colony’s population expanded westward, eastern elites refused to extend representation to the predominantly Scotch-Irish and German immigrants living in the new settlements.

Additionally, while Philadelphia had grown to become the most populous city in North America, political leaders from the surrounding counties refused to increase the city’s number of representatives. By the early 1770s, the state’s most radical voices in favor of revolution—Philadelphians and westerners—were systematically underrepresented in the legislature.

In the short term, the denial of proportional representation worked: Pennsylvania’s government, designed to amplify moderate and conservative voices, was notoriously slow to endorse resistance to Britain, and in 1776 refused to allow its delegates in the Continental Congress to vote for independence. By this point, though, Pennsylvania’s radicals had taken matters into their own hands.

Drawing on protest movements that had gathered pace in 1774 and 1775, they organized a series of conventions giving greater voice to the marginalized. When, in May 1776, the Continental Congress called on states to form their own governments, Pennsylvanians bypassed the colonial assembly entirely, and used the convention and committee movements to send pro-independence delegates to Congress and to write their own state constitution.

In September 1776, Pennsylvania’s radicals took their revenge. Each county was given more or less equal representation in the first legislature. This measure was about as biased toward the western counties as the previous arrangements had been toward eastern ones. But having been shut out of power for so long, the radicals were keen to ensure they held the reins.

Pennsylvania’s first constitution, by a long shot the most radically democratic of all the original 13 states’, was bitterly contested for the next decade. Conservative opponents tried, and failed, to revise the state constitution four times from 1776 until 1783. Though they finally succeeded in writing a new constitution in 1790, it came at the cost of 14 years of unstable and rancorous government.

Just decades later, in the antebellum period, similar dynamics played out once again. Slaveholding states sought to use constitutional arrangements to maintain minority power. The Missouri Compromise of 1820, which admitted slaveholding Missouri to the union at the same time as free Maine, maintained balance in the Senate between free and slave states. Southern politicians considered this balance vital, as it gave a de facto veto to slaveholding states.

But demographic change over the ensuing decades quickly meant that northerners outnumbered southerners. Yet only in the aftermath of the notorious Compromise of 1850, and the admission of California as a free state, did the balance between free and slave states snap—at a time when the population of free states was 13.4 million, well exceeding the 9.7 million inhabitants of slave states (of whom 3.2 million were enslaved and couldn’t vote). In the decade that followed, the South attempted to re-create its minority veto, with disastrous results.

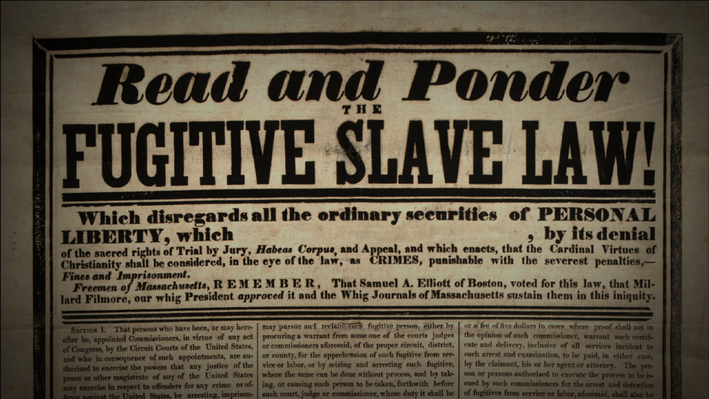

The politics of the 1850s became consumed with the question of slavery. Southern slaveowners insisted on a new Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which compelled northern authorities and other residents to actively participate in arresting and returning fugitive slaves to their enslavers. Northerners responded furiously, adopting antislavery politics in greater numbers.

Southerners, fearful of the growing strength of the abolitionist movement and the specter of a permanent electoral minority, demanded more slaveholding territory as the nation expanded westward—many called for slavery to be legal in all federal territories, and advocated foreign war to annex new slaveholding territory, such as Cuba.

In 1854, Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois attempted to broker a compromise between North and South with his Kansas-Nebraska Act. Allowing residents of the Kansas and Nebraska territories to vote on whether to allow slavery within their borders, the act was seen in the North as a naked attempt to extend slavery beyond the Missouri Compromise line and give greater weight to slaveholders in the Senate.

Voters in the North turned out in force, leading to the creation of the Republican Party and, ultimately, the election of Abraham Lincoln as president. The South’s attempts to continually impose minority rule on the North failed, leading to secession, the Civil War, and the greatest number of military casualties for a single war in American history.

Population shifts contributed to a third episode of minority rule in the early 20th century. Rapid industrialization in the years after the Civil War saw the growth of megacities that fundamentally transformed the demographics of several states. In Illinois, Chicago’s population grew from 112,000 in 1860—6 percent of total state residents—to 2.7 million in 1920, or 40 percent of total state residents. According to the state’s constitution, the state legislature should have reapportioned following each decennial census; from 1900 onwards, downstate leaders refused to do so, leaving Chicago heavily underrepresented and overtaxed.

In the 1920s, the repeated refusal of the downstate minority to reapportion the legislature was met with increasing frustration from Chicago representatives. Throughout the decade, the city council passed angry resolutions condemning the malapportionment. In 1925, with more and more time at council meetings devoted to the topic, the council passed a resolution calling for the city to secede from Illinois, and to form the State of Chicago.

Downstate defenders of the status quo continued to dig their heels in, even forming organizations such as the League for the Defense of Downstate Voters. Only in 1955 did the Illinois legislature finally bow to the inevitable, redistricting for the first time since 1901. Even then, downstate leaders struck a deal to maintain control in the state Senate, until Supreme Court rulings in Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964) decreed that state legislative-district populations be “of roughly equal size.” Ever since, Chicago and Cook County politicians have dominated Illinois elections.

What, then, of the prospects of minority rule at the federal level in the coming years? The coming years seem likely to see Republicans attempt to strengthen their grip on power despite their weakness at the ballot box. With the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, conservatives have a 6–3 majority on the bench, and important rulings loom on issues such as health care, abortion rights, and gay marriage.

Policies supported by a majority of Americans in opinion polls could be ruled unconstitutional, all because a president who lost the popular vote nominated three justices, and senators representing a minority of the American population confirmed them. With President-elect Biden likely facing a divided Congress, Democrats have no institutional means of turning electoral support into legislative action, to say nothing of fixing underlying representation issues.

But Republicans may not be able to sustain their power for long—at least not peacefully. As the cases above show, when parties commit themselves to minority rule, the backlash can be severe. While the letter of the law allows Republicans to control the Senate and the judiciary, the spirit of republican government demands otherwise. The two cannot long exist in tension with each other.

Though the 2020 election did not result in a blue tidal wave, it did suggest emerging Democratic majorities in formerly red states such as Arizona and Georgia. If, eventually, demographic change adds North Carolina and Texas to the mix, national elections would more accurately reflect the national popular vote. History suggests that Republicans would then pay—dearly—for their years of minority rule.

If Republicans hope for greater success than their historical counterparts, they would do well to heed the message that a party cannot maintain power forever, and embark on a more genuinely collaborative and bipartisan approach to government. Short of that, they risk much more than their political careers.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.