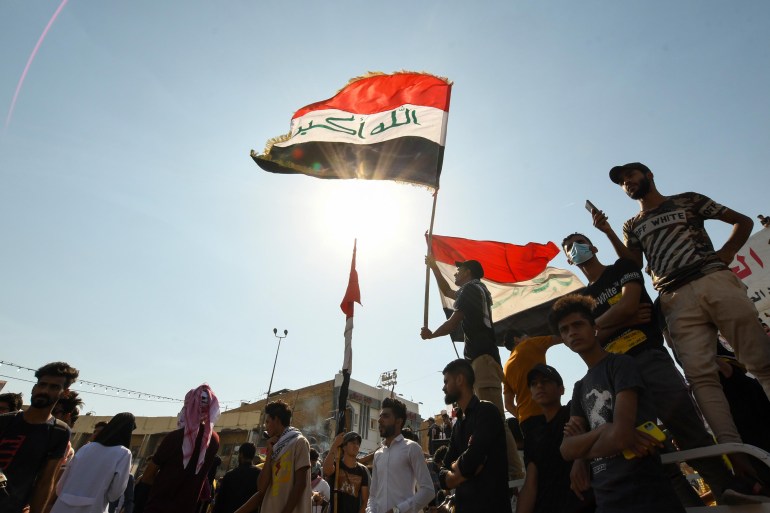

Iraqi demonstrators gather in Haboubi Square in Nasiriya on October 28, 2020.

Biden Should Not Repeat Trump and Obama’s Mistakes in Iraq

Zeidon Alkinani / Al Jazeera

Iraqi demonstrators chant slogans during a gathering in Haboubi Square in the southern city of Nasiriya on October 28, 2020

(December 14, 2020) — For more than 17 years since its invasion of Iraq, the United States has failed to present itself as a partner interested in supporting Iraqi efforts for democratic and economic development. It has continued to pursue its military and geopolitical interests at the expense of the Iraqi people, their security and wellbeing.

This became clear once again at the beginning of this year when, amid a popular uprising against rampant corruption, sectarian politics, political violence, unemployment, and Iranian interference in Iraq, the Trump administration decided to assassinate in Baghdad top Iranian General Qassem Soleimani.

Instead of backing the Iraqi people’s democratic aspirations, Washington once again propped up the dysfunctional political status quo by escalating its confrontation with Iran and in this way, undermining the movement for reform and political change.

In this context, the fact that US President Donald Trump is pursuing his own narrow political interests in Iraq in the last months of his presidency is hardly surprising to Iraqis. His decision to withdraw more US troops from the country is another attempt to present himself as fulfilling his election promises while setting yet another foreign policy trap for the incoming administration of Joe Biden.

In his pursuit of disastrous policies in Iraq, however, Trump is no different from his predecessors. And many Iraqis fear that his successor may bring more of the same.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/7FMIBPGJGZHELODTJZZ67EIR4U)

US-Iran Confrontation

Since President George W. Bush’s “mission accomplished” speech in May 2003, he and his successors have repeatedly talked about the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq, but have never fully or permanently carried it out.

This has been the case with Trump as well. In fact, despite his domestic rhetoric about ending the “forever wars” started by past administrations, the US president rejected the Iraqi parliament’s resolution calling for full US military withdrawal from the country.

The latest announcement of a “withdrawal” concerns just 500 of the 3,000 US troops currently deployed in Iraq. Like his predecessors, Trump is held back by certain considerations, particularly that the US needs a military presence in Iraq in order to defend its own economic and geopolitical interests. This is especially the case amid the escalating confrontation with Iran.

It is for the same reason that Trump had to backtrack on his decision in 2019 to pull out of Syria and leave 200 troops to “secure the oil”. Today, US military personnel in Syria are close to 1,000 by some estimates and serve as a foothold to counter Russian and Iranian influence in the area.

Thus, Trump has continued the policies of his predecessors of sending mixed messages on US military presence in Iraq, which has caused much uncertainty among Iraqi officials and the general public. But he has also made the situation worse by escalating tensions with Iran without having a clear-cut plan for containing it.

Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal with Tehran and his “maximum pressure” policy of expanding sanctions and stifling Iranian oil and trade revenues have provoked an aggressive response. Iran has sought to hit back against regional US allies as well as US positions in its immediate neighbourhood — i.e. Iraq.

Over the past two years, Tehran has mobilised its full Iraqi capabilities — from its loyal militias to its infiltrators in the Iraqi intelligence, security and governance structures — to confront the US. This has greatly destabilised Iraq, worsening security and undermining efforts for political reforms.

The response of the Trump administration has been completely incoherent. It has blamed Iraqis for Iranian attacks on US military and diplomatic assets and has threatened the Iraqi government with sanctions. It has effectively transformed Iraq into a battleground, with devastating consequences for the Iraqi population and its political movement for change.

The Trump administration’s behaviour has made it clear that it was after short-term strategic gains for domestic consumption rather than an actual long-term strategy to contain Iranian influence in Iraq, disempower its militias, and help Iraqi military and civilian institutions regain sovereign decision-making.

In this regard, again, Trump has only followed in the footsteps of his predecessors. This apparent American indifference towards the fate of the country has left many Iraqis feeling equally hostile to both Tehran and Washington.

Biden’s Policies in Iraq

Having gone through the same failed policies of three consecutive US presidents since 2003, many Iraqis are cautious about expecting much from the upcoming Biden administration.

The Iraqi Kurds are probably the most optimistic about his presidency. They hope he could be “America’s most pro-Kurdish president”, given his past statements on Kurdish statehood and ties with Erbil’s leadership.

Iraq’s Sunni Arabs, who once denounced the US occupation because of their marginalisation on the political scene, are now in favour of a US military presence against the enormous Iranian influence. Biden’s willingness to expand the deployment of US troops will probably be welcomed by Sunni Arab political circles.

The Shia Arabs are ambivalent at best. The elites — the majority of whom adopt a pro-Iran discourse — will probably evaluate Biden’s administration based on its approach to de-escalation with Iran. But there are also many among the ordinary Shia population who are frustrated by both Tehran and Washington. They would like to see the Iranian grip on Iraq relax and a strong Iraqi national state emerge, but their bitter experience with Trump during the protests of 2019-2020 has dampened their hopes that the US can be an effective anti-Iran influence.

Biden himself has a mixed record on Iraq as a senator and vice president. In June 2006, he proposed a soft partition of Iraq to allow for federal autonomy for the Shia Arab, Sunni Arab, and Kurdish communities, which was welcomed by the Kurds, but rejected by many Arabs.

He continued to promote his plan even amid the war against ISIL (ISIS), calling in a 2014 Washington Post article for “functioning federalism… which would ensure equitable revenue-sharing for all provinces and establish locally rooted security structures”.

Biden would do well to drop this proposal from his foreign policy objectives in Iraq. Solidifying political divisions between the different communities would encourage more political fragmentation and provide even more ground for the expansion of Iranian influence. A semi-autonomous Shia region would most likely fall completely under the control of Tehran.

Biden has also voiced his support for maintaining a US military presence in Iraq and Syria, but it would be challenging for him to redeploy troops to Iraq, as American public opinion is generally against it. If the security situation remains the same, his administration will likely keep the same number of troops in Iraq.

At the same time, some observers believe that he will follow Obama’s policy on Iraq — i.e. look for an opportunity for a full withdrawal and de-escalation with Iran. On the campaign trail, Biden has made it clear that he wants to re-enter the nuclear deal with Iran, but on what terms, it is still unclear.

Trump has put on the table a new set of conditions for renegotiating the agreement, including a halt on Iran’s ballistic missile programme. It remains to be seen whether Biden will backtrack on those, but he is under pressure from US allies not to ignore Iran’s destabilising activities in the Middle East as Obama did. Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud recently stated that Saudi should be a “partner” to any future agreement.

From an Iraqi perspective, a new round of negotiations could be a perfect opportunity for the US to strike a deal with Iran on Iraq. Tehran will always remain a factor in Iraq politics by virtue of its neighbouring location, its sheer size, and the close cultural, religious and economic ties between the two countries. But that does not mean that Iranian interference cannot be curbed. A deal with the West may be able to achieve that, at least to a certain extent, but enough to give Iraqis the chance to pursue reform and meaningful political change.

After decades of disastrous policies on Iraq, it is time for the US to learn from its mistakes. The Biden administration must side with the Iraqi people and help clear the rubble the US’s war and occupation have left behind. It must do its part — take care of the pervasive Iranian interference it let into the country with the 2003 invasion — and allow Iraqis to rebuild their country.

Zeidon Alkinani is a political analyst and researcher on Iraq and the Middle East. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.