How the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Impacts the US, and Why Washington Must Embrace its Entry into Force

Alicia Sanders-Zakre and Seth Shelden / The Journal of International Affairs

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY (January 15, 2021) — The United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) will enter into force on January 22, 2021, two days following the inauguration of Joseph Biden as the 46th president of the United States.

Despite the TPNW’s widespread support throughout the world, the United States has attempted to thwart the treaty’s progress at every step, boycotting the negotiations from the start and urging other countries to withdraw as the treaty neared its entry into force. These efforts have proven unsuccessful. This article explores the implications of the entry into force of the TPNW, with special attention to the United States and how the new Biden administration can play a more constructive role in the international treaty regime.

On January 20, Joseph Biden will become the next U.S. President. Two days later, on January 22, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) will become binding international law. The Biden administration should seize the opportunity to sign this landmark treaty and work toward its ratification, while productively engaging with the new legal regime created by the treaty.

With the TPNW, nuclear weapons will be subject to a global ban treaty for the first time, at last aligning nuclear weapons with other weapons of mass destruction, all already the subject of treaty-based prohibitions. The TPNW provides a framework to verifiably eliminate nuclear weapons and requires its States Parties, i.e., states that have ratified or acceded to the treaty, to assist victims and remediate environments affected by nuclear weapons use and testing. The treaty was negotiated in recognition of the increasing likelihood of use of nuclear weapons, whether intentionally or accidentally, and the catastrophic humanitarian consequences that would result from any such use.

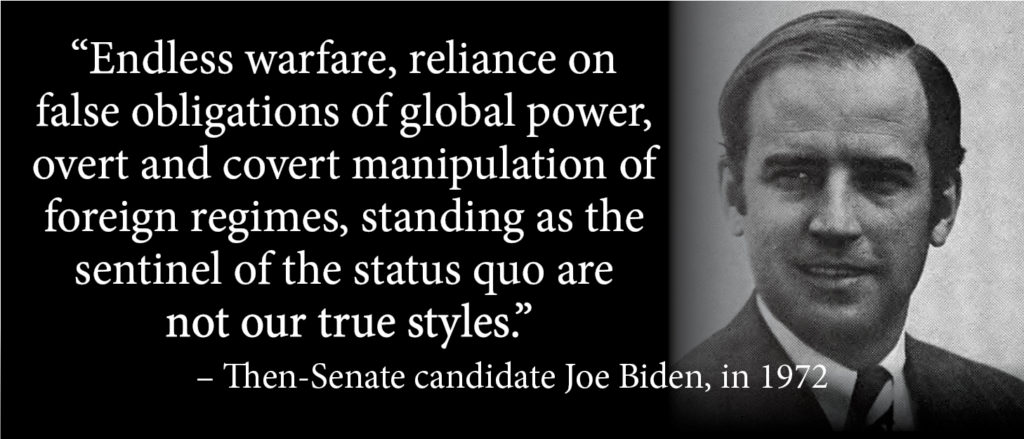

The United States has aggressively attempted to thwart the TPNW despite support for the treaty from more than two-thirds of the world’s states. These efforts have been unsuccessful. If President-elect Biden truly intends “to prove to the world that the United States is prepared to lead again—not just with the example of our power but also with the power of our example,” his administration must reverse the U.S. position on the TPNW.

Past United States Approach to TPNW

Before treaty negotiations had begun, in a 2016 nonpaper the United States urged NATO members to vote against proceeding with the initiative, claiming that such a treaty would “undermine…long-standing strategic stability.” Despite U.S. urging, the resolution to proceed with negotiations was adopted in December 2016 with clear global support.

After Donald Trump assumed the presidency, the United States intensified its opposition, publicly dismissing and ridiculing the TPNW while privately pressuring countries not to support it. On the first day of treaty negotiations, U.S. Ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, hosted a press conference outside the room where negotiations were to take place, criticizing the pursuit of a prohibition treaty and questioning if nations participating were “looking out for their people.”

In October 2020, as the treaty approached the threshold of 50 ratifications for its entry into force, the United States sent a letter to countries that had joined the TPNW, restating its “opposition to the potential repercussions” of the treaty and encouraging states to withdraw their instruments of ratification.

Once the treaty reached 50 States Parties, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Christopher Ford retweeted his remarks from 2018 in which he had called the treaty “harmful to international peace and security.” China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States have consistently issued joint statements disparaging the treaty at various international fora, including the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) General Conference, the United Nations General Assembly, and Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) meetings.

U.S. opposition to the TPNW is predicated on the falsehood that nuclear weapons provide security, as well as mischaracterizations about the treaty itself. Despite legal obligations and decades of commitments to bring about a world without nuclear weapons, in truth the United States relies steadfastly upon deterrence doctrines that are incompatible with these obligations and commitments, and it views any threat to the legitimacy of nuclear weapons as a threat to its national security.

In clutching to deterrence doctrines, despite recognition—even from conservatives and libertarians—that nuclear weapons offer no military or practical value, U.S. policymakers undoubtedly are influenced also by the trillion dollar industry supporting its nuclear weapon arsenal. They thus have advanced spurious claims about the TPNW’s failings, arguing that the treaty will undermine the NPT, weaken IAEA safeguards, and only impact democracies, all of which are untrue.

These false assertions have been debunked in numerous more thorough examinations, so it suffices to say that the majority of countries do not share U.S. and like-minded states’ concerns about the TPNW, which former IAEA Director General Hans Blix characterized as “excessive” and technically “strained.” These supportive countries recognize instead that the treaty complements existing structures to reduce nuclear threats. The United States’ last-minute attempt to prevent the treaty from reaching entry into force, by asking states to withdraw ratifications, underscores how ineffective and misguided the U.S. approach to the TPNW has been.

This aggressive opposition did not impede countries from signing and ratifying the treaty, nor did it diminish global support. A recent study on public opinion in Japan, for example, demonstrates that widespread support for the treaty was not swayed by critical arguments, including U.S. arguments that the TPNW might undermine security or other nuclear treaties.

To the contrary, support for the TPNW is such that the treaty reached the necessary threshold of 50 States Parties required for it to enter into force during a global pandemic. Despite many parliaments worldwide slowing or ceasing work throughout 2020, the TPNW’s accession rate remains comparable to the rate of other disarmament treaties. In December 2020, 130 countries voted in favor of the UN General Assembly resolution welcoming the treaty and calling on all states to join.

Nuclear-armed states aggressively denouncing an initiative with global support impairs unity in other international fora needed to advance other nuclear disarmament, nonproliferation, and risk reduction measures.

Implications of Entry Into Force

U.S. denouncements of the TPNW also ignore the significant impact of this treaty internationally, and on the United States itself. When the TPNW enters into force, States Parties will immediately need to adhere to the treaty’s Article 1 prohibitions, prohibiting them from developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, acquiring, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using, or threatening to use nuclear weapons, or allowing nuclear weapons to be stationed in their territories. It also prohibits States Parties from assisting, encouraging, or inducing anyone to engage in these activities.

Under Articles 6 and 7 of the TPNW, States Parties also are obligated to assist victims of and remediate environments contaminated by nuclear weapon use and testing. These “positive obligations” break new ground in international nuclear weapons law. States with affected victims and contaminated lands under their jurisdiction have the primary responsibility for providing assistance, in a nod to state sovereignty and practical facilitation.

However, Article 7 requires all States Parties to cooperate in implementing the treaty and, particularly for those in a position to do so, to assist affected states. States Parties may also implement Article 7 by helping other states to abide by other articles, such as adopting national laws to implement the treaty, or cooperating on initiatives to promote universalization to the treaty.

States Parties’ implementation of the TPNW will impact states not party, including the United States. For example, in fulfilling its TPNW Article 12 obligations, States Parties may urge the United States to join the treaty in bilateral meetings. Creating strong international standards for victim assistance to implement TPNW Article 6 could build support in the United States to expand and extend the Radiation Compensation Exposure Act, which provides assistance to some U.S. nuclear testing victims but not to all. The United States could also contribute to victim assistance programs established by the treaty, similar to how it contributes funds to assist landmine victims despite not being party to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention.

While the TPNW creates legally binding obligations only for States Parties, it reinforces existing law, applicable to all states, regarding non-use and elimination of nuclear weapons, and it furthers norms against nuclear weapons. As norms shift, incentives may shift also, and states not party may be expected to change behavior due to the increased stigmatization of nuclear weapons.

After the entry into force of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention and the Cluster Munitions Convention, for example, states that had not joined those treaties nevertheless changed policies on use and transfer of those weapons, companies based in states not party ceased production of the prohibited weapons, and financial institutions in states not party ceased investing in producing companies. Even before the TPNW’s entry into force, we have seen similar effects for nuclear weapons. For example, despite the Netherlands not being party to the TPNW, the Dutch pension fund ABP chose to stop investing in companies producing nuclear weapons, citing their prohibition under the TPNW.

Recommendations for Biden Administration

Instead of pursuing the ineffective strategies of the Obama and Trump administrations and hoping for different results, the new Biden administration should sign the TPNW, submit it to the Senate for ratification, and take immediate steps to more constructively engage with the treaty’s regime.

President-elect Biden has promised “to work to bring us closer to a world without nuclear weapons, so that the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are never repeated.” He has affirmed that, “as the only nation to have used nuclear weapons, we bear a great moral responsibility to lead the charge” to a nuclear-weapon free world, “because that is the only surety we have against the nightmare scenario becoming a reality.” And he has acknowledged that the United States has both the legal obligation and the strategic incentive to do so.

Continued reliance on nuclear deterrence—a doctrine that would be better characterized as “luck-based security”—has increased the risk of nuclear Armageddon to its highest point in history, higher even than at any point during the Cold War. We increasingly understand how the climate crisis both compounds and is compounded by the risks posed by nuclear weapons, and we increasingly understand how nuclear conflict would affect the United States even if occurring in other parts of the world. Any use of nuclear weapons, anywhere, would result in unacceptable, long-term consequences for which there can be no adequate response.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates further the challenges of responding to global health catastrophes, and how poorly we allocate resources to address true security risks. Investing trillions of dollars in weapons with no legitimate military or strategic function is the antithesis of security.

A number of smaller steps are important to reduce nuclear risks, but a bolder disarmament agenda will be necessary to bring about a truly secure world. Along with the climate crisis, decisive action toward the elimination of nuclear weapons is needed now, before it becomes too late. The 122 countries that adopted the TPNW in 2017 are taking such decisive action.

Were Biden to move the United States to join the TPNW, his administration could lead the nine nuclear-armed states toward a saner future, and could be at the forefront of a new multilateral order, one supported already by the world’s fastest-growing countries.

Many political leaders from nuclear-armed and allied states support joining the TPNW. This past September, 56 former leaders from 20 NATO countries, plus Japan and South Korea, including two former NATO secretaries-general, called upon their governments to join. In the United States, the recognition of the treaty’s merits has come from both sides of the political aisle, from former Obama administration officials to an assistant defense secretary from the Reagan administration. United States cities and states have called upon the United States to join, as have members of Congress.

To realize a future without nuclear weapons, the United States must join the TPNW. In the meantime, the Biden administration must take three immediate steps to shift the United States approach to the treaty:

A. Cease calling on states to withdraw from the TPNW and stop pressuring them not to join. This includes repudiating the October 2020 letter—as South Africa’s Ambassador to the UN, Nozipho Mxakato-Diseko, reacted, for as long as it remains United States policy that states should withdraw from the TPNW, the United States undermines all multilateralism, including under the NPT.

B. Acknowledge that the TPNW does not contradict or undermine the NPT or other treaties relating to nuclear weapons non-proliferation, arms control, and disarmament, but instead complements and reinforces them.

C. Recognize that the TPNW is a significant initiative to strengthen the global norm against nuclear weapons, and, as UN Secretary-General António Guterres has stated, “a meaningful commitment towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons.”

Looking Ahead

President-elect Biden faces many nuclear weapons policy challenges as he takes office. Under the Trump administration, the United States withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, and the Open Skies Treaty, and did not extend New START, all while urging other countries to not join, or even to withdraw their ratifications to, the TPNW. The United States has a chance to return to the table on multilateral nuclear negotiations and build back better.

The TPNW is a landmark international treaty with support from most of the world’s governments. It offers security in a world where nuclear weapons offer none. Global civil society stands behind it, including the Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, composed of young people, scientists, hibakusha, and doctors in 106 countries. Faith leaders, including the head of the Catholic Church Pope Francis, champion the treaty as well.

After decades of rhetoric about the need to eliminate nuclear weapons, the United States has an opportunity under new leadership to join the treaty that provides a pathway to that end. As the United States works to join the TPNW, it must immediately reverse its aggressive posture against the treaty and its supporters. President-elect Biden has the opportunity to be part of an effort that finally rids the world of nuclear weapons. He would do well to take it.

Alicia Sanders-Zakre is the policy and research coordinator of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and the author of over 100 articles, editorials, and reports on nuclear weapons and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Seth Shelden is a lawyer and law professor who works as the United Nations Liaison for the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), where he promotes the universalization of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.