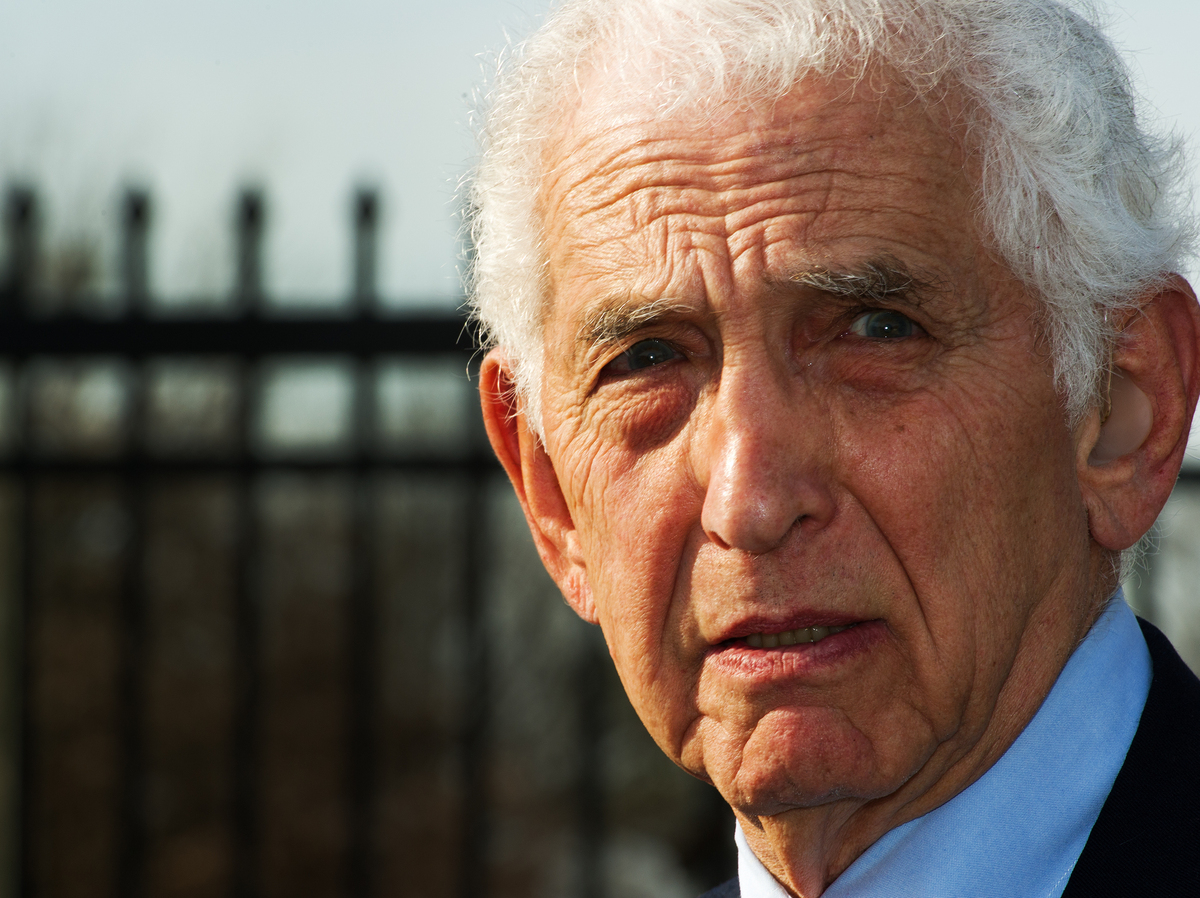

Daniel Ellsberg Isn’t Stopping Now

Sasha Abramsky / The Nation

(March 26, 2021) — On the cusp of turning 90, Daniel Ellsberg sits in his book-and-box-cluttered office in his home in Berkeley, Calif., and prepares to discuss his life credo — and his future plans. He is, geographically and temporally, a long way away from his youth, spent in Chicago and Detroit, when he hero-worshipped labor leaders such as Walter Reuther and dreamed of himself one day becoming a union organizer.

“Hope is not a feeling or an expectation,” he explains of his worldview, which he hews to after witnessing nearly a century’s worth of wars. “It’s a form of acting. I choose to act as if we had a choice to change this behavior, and to change the world for the better and avoid catastrophe.”

Ellsberg, who nowadays describes himself as a Scandinavian social democrat in the style of the late Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, has long been preoccupied by the possibility of nuclear war. This preoccupation began when he was in junior high, at the tail end of World War II, after a teacher mentioned the science behind a putative nuclear bomb, months before the A-bombs were actually dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“I had learned about as a possibility, as a 13-year-old in a social studies class looking into the question of the implications for humanity, of a bomb 1,000 times more powerful than the blockbusters we were then seeing on newsreels,” he recalls. “My teacher said there was a possibility of a Uranium-235 bomb. It didn’t take long for 13-year-olds to conclude that humanity wasn’t up to that. It would not be a good thing. It would have very ominous implications for humanity. Nine months later, I saw a headline saying we’d destroyed a city with one bomb.”

Ellsberg came of age in the years after the war ended, when the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics were first starting the dance of death that would result in a more than 40-year Cold War. He studied economics at Harvard, and then spent a year in the United Kingdom, at Cambridge University, before returning to the States and enrolling in the Marine Corps in 1954. Subsequently, Ellsberg returned to Harvard, to study for a PhD in economics. At the same time, he started working as a strategic analyst, putting his sharp mind to use analyzing the strategic problems of the burgeoning Cold War.

“In 1958,” he continues, “I found myself at the RAND Corporation reading top-secret estimates that the Soviets were preparing to wipe out our Strategic Air Command with ICBMs, and the only way to avert that was for us to have the capability to retaliate in a large way. I got into the problem of actual war plans, with no other intention than to avert such a war.”

Ellsberg pauses. Since those days, nearly 65 years ago, he has believed that humanity is on a collision course with catastrophe as a result of the nuclear policies pursued by the Great Powers, particularly the United States, and he has been haunted by a sense of deep responsibility to sound the alarm.

“In most respects we are not the worst empire that ever was. But we have one peculiarity: We invented the Doomsday Machine as a tool of our influence. We can destroy cities with firestorms that can lift smoke to the stratosphere, cut off sunlight, cause ice age conditions and starve most everyone to death within a year,” he says, describing the possibility of a nuclear winter. “It would leave 1 to 10 percent alive. But we would have killed off about 7 billion people. We’ve had the capability since about 1950.”

In the 1960s, his angst about potential nuclear annihilation morphed into a more widespread opposition to the concept of wars waged by superpowers in and against smaller countries. He traveled to Vietnam to study conditions on the ground, as the war escalated during the Johnson presidency. While there, he slowly but surely came to the conclusion that the war was not only immoral but also unwinnable. And, upon his return Stateside — a move precipitated by his falling ill with hepatitis — he told this to anyone whose ears he could catch, be they Defense Secretary Robert McNamara or Ambassador Averell Harriman.

When these senior figures didn’t listen, when the war continued and the list of lives lost grew longer by the hour, he made the momentous decision to go public with his insider knowledge that that war was based on a web of lies.

The Pentagon Papers were published by the The New York Times starting on June 13, 1971, nearly two years after Ellsberg first made copies at the RAND Corporation offices and carried them out the door in a briefcase. Upon their publication, following initial reports on their contents by Times journalist Neil Sheehan, they created a sensation, detailing years of government malfeasance and dishonesty surrounding the Vietnam War.

Ellsberg shot to national fame: For millions, the previously anonymous policy analyst was a sudden hero of the anti-war movement; for other millions, he was Public Enemy Number One. Nixon’s Justice Department charged him under the Espionage Act and attempted to have him put away for more than a century; but, with famed civil rights attornies Leonard Boudin and Leonard Weinglass representing him, the case was ultimately thrown out.

Half a century after Ellsberg’s leaking of the Pentagon Papers, he shows no signs of slowing down. His hair now a shock of white, he remains in the intellectual thick of things, a powerful, sprightly figure in the anti-nuclear and anti-militarism worlds. As he sits in front of his computer — Zoom is easier for him to hear, he explains, than are in-person meetings — in a thin black jacket and a black sweater, his ears cradled in large headphones, he periodically reaches over to one side to pick up fistfuls of snacks. A vast number of books populate his office, piled along the shelves around him. When he gets animated — which is frequently — he leans into the camera to talk, his voice crisp and clear, determined neither to lose his audience nor to sound like an old man.

Sheehan died last year, and obituaries were quick to suggest that he stole and copied the Pentagon Papers from Ellsberg after the analyst reputedly got cold feet about the legal peril he might face. Ellsberg has a very different memory, sharply objecting to any hint that he wasn’t intent on with going public with what he had discovered during his deep digs through the Pentagon archives.

He was always willing to give the papers to Sheehan, he says, but he wanted a cast-iron guarantee that the newspaper would actually have the guts to publish them. To his frustration, the journalist avoided giving him a straight answer about whether the Times was genuinely committed to the project. “I didn’t want a copy lying around in an institution that wasn’t going to use it,” Ellsberg recalls. But, he continues, once he found out the newspaperwas going to run the Pentagon Papers, “I was nothing but happy.”

Happiness isn’t a state of mind that Ellsberg wears on his sleeve. In fact, he’s tormented by a risk analyst’s knowledge of just how precarious modern human civilization has become. He worries that in the 20-year Afghanistan conflict America has repeated many of the same mistakes and atrocities it undertook in Vietnam, and he grieves that there isn’t more widespread public opposition to these actions.

“If the Pentagon Papers of Afghanistan come out, you could change place names and officials’ names,” he says. “It wouldn’t make any difference. Same story. And we were lied into a war with Iraq. And Trump could have gotten us into a war with Iran. If you look at Obama in Libya, he wasn’t even willing to use the War Powers Act to inform Congress. It was just war from the air. We’re seeing near-zero curiosity in the American public as to how many Afghans have been killed in this war in the last 20 years. Not an estimate, no hearings. How about Iraq? There are estimates about 10 to 20 times that of the government estimates. The American people don’t care.”

The older he gets, the more Ellsberg sees himself as being on a moral mission to open eyes kept deliberately shut by those who would prefer to avoid having to deal with the crises of our times. To get them to see the perils of nuclear war. The perils of militarism. And, most recently, the perils of climate change.

“We are on the Titanic, going full speed ahead on a very dark night, into what we have been warned are ice-filled waters,” he says. “On climate, we’ve already hit the iceberg. On nuclear, we haven’t hit the iceberg yet. What the captain of the Titanic could have done when he got the warning of ice is do what other ships did: stop dead in the water, go slowly, or go south. Instead, he kept on course, full speed, in the dark. He gambled. That’s what we’ve been doing for 70 years.”

The OG of national security whistleblowers pauses. Perhaps, I suggest, now that he’s almost a nonagenarian, he might slow down a bit, pass the baton on to younger people who have taken up the cause of warning the world about the dangers of nuclear war.

Not a chance. “I will be trying to alert people to that till the day I die,” he announces. “I think our nuclear policy is as dangerously delusional as the belief that the pandemic is a hoax and there is no man-made climate change. At 90, I’ve come to realize that vast delusions are not only possible but probable.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.