The US Helped Craft the Most Important International Treaty to Protect Nature — but Won’t Join It

Benji Jones / Vox

(May 20, 2021) — As President Joe Biden moves quickly to reinstate the full slate of environmental policies weakened by former President Donald Trump, including the landmark Migratory Bird Treaty Act, he’s signaling that climate change and biodiversity loss are now major priorities for the US.

Earlier this month, the Interior Department also launched a campaign to conserve 30 percent of US land and water by 2030, joining more than 50 other countries that have committed to that goal. Biden is pursuing the target, known as 30 by 30, alongside a new and more ambitious commitment to cut carbon dioxide emissions.

Yet there’s one big problem with this post-Trump environmental renaissance: The US still hasn’t joined the most important international agreement to conserve biodiversity, known as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). And it isn’t just a small, inconsequential treaty. Designed to protect species, ecosystems, and genetic diversity, the treaty has been ratified by every other country or territory aside from the Holy See.

America’s absence from the Convention on Biological Diversity

hurts global efforts to avert extinction

Among other achievements, CBD has pushed countries to create national biodiversity strategies and to expand their networks of protected areas.

Since the early 1990s — when CBD was drafted, with input from the US — Republican lawmakers have blocked ratification, which requires a two-thirds Senate majority. They’ve argued that CBD would infringe on American sovereignty, put commercial interests at risk, and impose a financial burden, claims that environmental experts say have no support.

With Biden now in office, some experts see a pathway to ratification — certainly, environmental groups are calling for it — while others say there’s no chance of wooing enough Republicans. But they all agree on one thing: The US’s absence from the agreement harms biodiversity conservation at a time when such efforts are desperately needed.

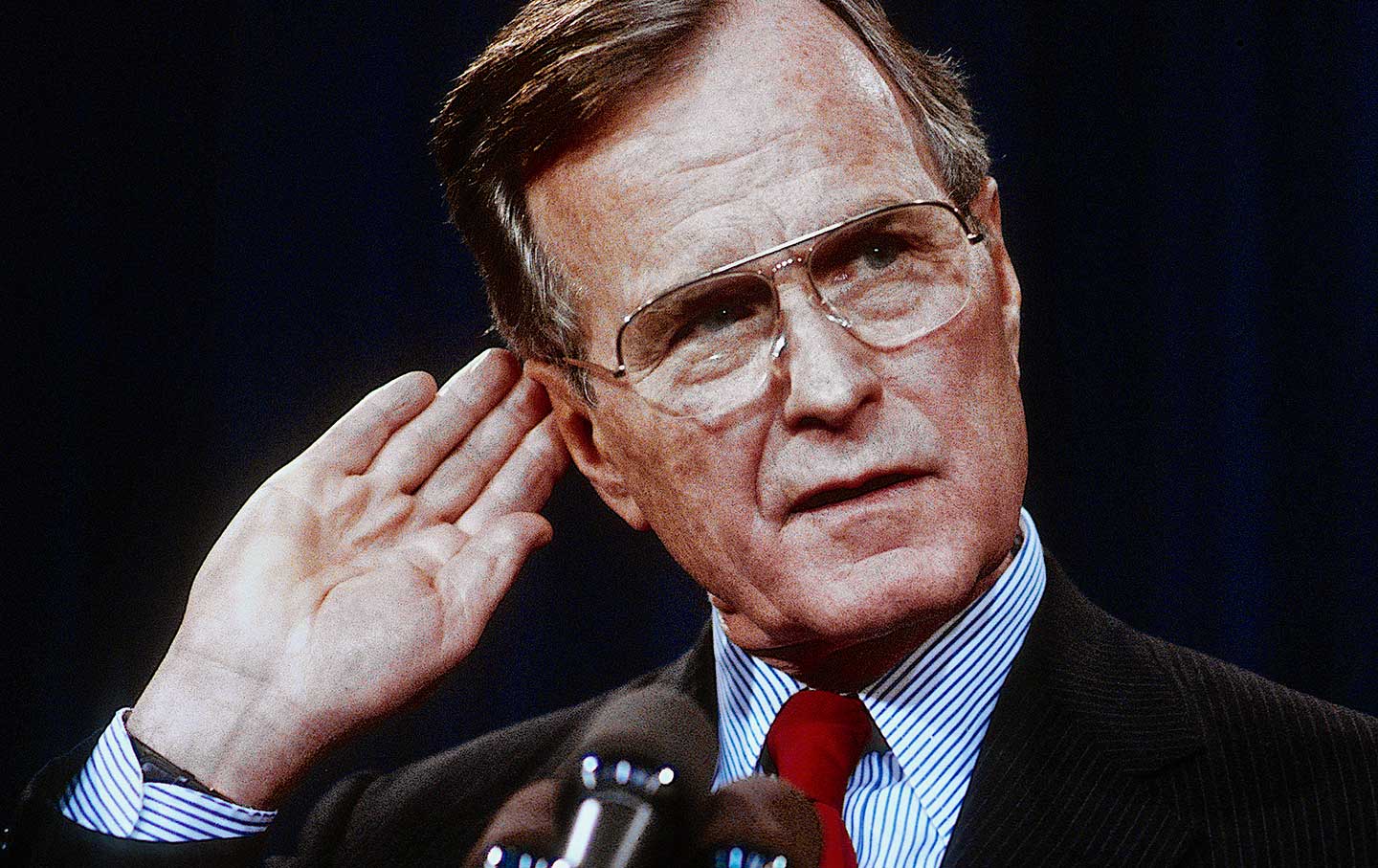

President Bush Refused to Sign a Biodiversity Treaty That the US Helped Craft

Nearly half a century ago, scientists were already warning that scores of species were at risk of going extinct — just as they are today. In fact, headlines from the time are eerily familiar: “Scientists say a million species are in danger,” read one in 1981, which is almost identical to a headline from 2019.

Those concerns ignited a series of meetings among environmental groups and UN officials, in the ’80s and early ’90s, that laid the groundwork for a treaty to protect biodiversity. US diplomats were very much involved in these discussions, said William Snape III, an environmental lawyer and an assistant dean at American University and senior counsel at the Center for Biological Diversity, an advocacy group.

“It was the United States who championed the idea of a Biodiversity Treaty in the 1980s, and was influential in getting the effort off the ground in the early 1990s,” Snape wrote in the journalSustainable Development Law & Policy in 2010.

In the summer of 1992, CBD opened for signature at a big UN conference in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It laid out three goals: conserve biodiversity (from genes to ecosystems), use its components in a sustainable way, and share the various benefits of genetic resources fairly.

Dozens of countries signed the agreement then and there, including the UK, China, and Canada. But the US — then under President George H.W. Bush — was notably not one of them. And it largely came down to politics: It was an election year that pitted Bush against then-Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, and a number of senators in Bush’s party opposed signing the treaty, citing a wide range of concerns.

Among them was a fear that US biotech companies would have to share their intellectual property related to genetics with other countries. There were also widespread concerns that the US would be responsible for helping poorer nations — financially and otherwise — protect their natural resources, and that the agreement would put more environmental regulations in place in the US. (At the time, there was already pushback, among the timber industry and property rights groups, on existing environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act.)

Some industries also opposed signing. As environmental lawyer Robert Blomquist wrote in a 2002 article for the Golden Gate University Law Review, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association and Industrial Biotechnology Association both sent letters to Bush stating that they were opposed to the US signing CBD due to concerns related to IP rights.

President Clinton Signed the Treaty but Failed to Find Support for Ratification

In 1992, Clinton won the election and, in a move hailed by conservationists, signed the treaty shortly after taking office. But there was still a major hurdle to joining CBD — ratification by the Senate, which requires 67 votes.

Clinton was well aware of the CBD opposition in Congress. So when he sent the treaty to the Senate for ratification in 1993, he included with it seven “understandings” that sought to dispel concerns related to IP and sovereignty. Essentially, they make it clear that, as party to the agreement, the US would not be forced to do anything, and it would retain sovereignty over its natural resources, Snape writes. Clinton also emphasized that the US already had strong environmental laws and wouldn’t need to create more of them to meet CBD’s goals.

In a promising step, the bipartisan Senate Foreign Relations Committee overwhelmingly recommended that the Senate ratify the treaty, making it seem all but certain to pass. At that point, the biotech industry had also thrown its support behind the agreement, Blomquist wrote.

Nonetheless, then-GOP Sens. Jesse Helms and Bob Dole, along with many of their colleagues, blocked ratification of the convention from ever coming to a vote, Snape said, repeating the same arguments. The treaty languished on the Senate floor.

And that pretty much brings us up to speed: No president has introduced the treaty for ratification since.

GOP Lawmakers Still Resist Treaties — Any Treaties

Two and a half decades later, concerns related to American sovereignty persist, especially within the Republican Party, and keep the US out of treaties. Conservative lawmakers stand in the way of not only CBD but also several other treaties awaiting ratification by the Senate, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities.

“Conservative nationalists in the United States (including the Senate) have long mistrusted international agreements,” Stewart Patrick, director of International Institutions and Global Governance at the Council on Foreign Relations, said in an email to Vox. They view them, he added, “as efforts by the United Nations and foreign governments to impose constraints on US constitutional independence, interfere with US private sector activity, as well as create redistributionist schemes.”

In other words, not a whole lot has changed.

A week after Biden was sworn into office, the Heritage Foundation, an influential right-wing think tank, published a report calling on the Senate to oppose a handful of treaties while he’s in office, “on the grounds that they threaten the sovereignty of the United States.” They include CBD, the Arms Trade Treaty, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, among others. (Environmental treaties like CBD tend to draw a stronger opposition from conservative lawmakers, who often fear environmental regulations, relative to other agreements, Snape said.)

Legal experts say concerns related to sovereignty aren’t justified. The agreement spells out that countries retain jurisdiction over their own environment. Indeed, US negotiators made sure of it when helping craft the agreement in the ’90s, Patrick recently wrote in World Politics Review. “States have … the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental policies,” reads Article 3 of CBD. (Article 3 goes on to say that states are also responsible for making sure they don’t harm the environment in other countries.)

“The convention poses no threat to U.S. sovereignty,” wrote Patrick, author of The Sovereignty Wars.

And what about the other concerns? The agreement stipulates that any transfer of genetic technology to poorer nations must adhere to IP rights in wealthier nations, Patrick writes. Clinton’s seven understandings also affirmed that joining CBD wouldn’t weaken American IP rights, and clarified that the treaty can’t force the US to contribute a certain amount of financial resources.

Joining the CBD is also unlikely to require anything in the way of new domestic environmental policies, Snape and Patrick said. “The U.S. is already in compliance with the treaty’s substantive terms: It possesses a highly developed system of protected natural areas, and has policies in place to reduce biodiversity loss in environmentally sensitive areas,” Patrick wrote.

Then again, given the country’s strong environmental laws, does it even matter if the US joins the agreement?

It Would Be a Big Deal If the US Joined CBD

Many environmental groups and researchers say, yes, it does matter and are urging Biden to work with the Senate to ratify CBD. In a January 8 op-ed published in the Hill, Sarah Saunders, a researcher at the National Audubon Society, and Mariah Meek, an assistant professor at Michigan State University, wrote that “global biodiversity policy is at a pivotal crossroads, and the US needs to have a seat at the table before it is too late.” They also urged the US to fully fund the CBD secretariat, which oversees the convention.

The convention has its big meeting this coming fall in Kunming, China, at which parties will build a strategy for biodiversity conservation over the next decade and out to 2050, that’s likely to include a 30 by 30 pledge. The US plans to send a delegation to the conference, the State Department confirmed with Vox, but as a non-member, the country doesn’t have the right to vote (such as on CBD procedures, including the location of a meeting, and in elections for various leadership roles).

Some experts, including Patrick of the Council on Foreign Relations, say ratification is still possible. Conservation is among the few issues that have bipartisan support, he writes, mentioning that nearly a third of US House and Senate members are a part of the bipartisan International Conservation Caucus (ICC). (Vox reached out to all eight ICC co-chairs, including four GOP lawmakers. They all declined interview requests or did not respond.)

“Eventual US accession is possible,” Patrick wrote, assuming the treaty is accompanied by “specific reservations, understandings, and declarations to reinforce the intellectual property rights of American companies and mollify conservative Republican senators with unrealistic fears that the convention could undermine U.S. sovereignty.”

That sounds a lot like what Clinton tried to do back in the ’90s, leaving others with little optimism. Snape, for one, says there’s no chance of ratification in the next two years — and unlikely in the next 10. That view is shared by Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity. There’s simply not enough appetite among GOP lawmakers to sign treaties of any kind, they said. To get the required 67 votes, you’d need 17 of their votes, assuming all Democrats voted in favor of ratification.

(In response to a request for comment, the White House directed questions about the treaty to the State Department. A State spokesperson said the US “has always supported the objectives of the CBD and continues to be actively involved in its processes.” The department declined to comment on whether Biden would make ratifying the treaty a priority.)

But what experts can all agree on is that, by failing to join CBD, the US — which has a huge environmental footprint — is hampering global conservation efforts. “Our absence from the CBD keeps international biodiversity ‘out of sight, out of mind’ at a time when its priority needs to be elevated,” Brian O’Donnell, director of Campaign for Nature, a conservation group advocating to conserve at least 30 percent of Earth by 2030, said by email.

Nature isn’t bound by political borders, O’Donnell said. So, reaching the goals of CBD — which we have so far failed to do — requires international cooperation and coordination. The US’s absence makes that harder, he said. The US is also home to some of the world’s best conservation researchers and tools, including those used for monitoring wildlife populations, Snape added. “The rest of the world needs us,” he said.

There’s another key reason to join the agreement: The US could help other countries develop conservation strategies that don’t come at the expense of Indigenous people and local communities, which has been the case historically.

While the US is itself guilty of harming native populations for the sake of protecting wildlife (most famously when creating Yellowstone National Park), the country is trying to turn a new leaf on conservation, under the direction of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo. In its new 30 by 30 initiative, Interior vowed to do right by tribal organizations.

“Now that there’s a chance the US does the right thing on conservation, it’s important for them to join [CBD],” said Andy White, a coordinator at the nonprofit Rights and Resources Initiative. “The US participating in the CBD could bring a more rights-based approach to conservation.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.