Biden Continues Trump’s Level of Nuclear Funding

Kingston Reif / Arms Control Today

(July/August 2021 Issue) — As the Biden administration prepares to initiate a review of US nuclear weapons policy, its first budget request would continue the expensive and controversial nuclear weapons sustainment and modernization efforts it inherited from the Trump administration.

The submission has prompted mixed reactions in Congress. Republicans have generally expressed support, but some Democrats said it is inconsistent with the concerns President Joe Biden raised on the campaign trail about the ambition and price tag of the modernization plans, which grew significantly over the past four years.

A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report published in May estimated the cost of the Trump administration’s approach at $634 billion from fiscal years 2021 through 2030. (See ACT, June 2021.) That is an increase of $140 billion, or 28 percent, from the CBO’s previous 10-year projection two years ago. (See ACT, March 2019.)

Whether the fiscal year 2022 budget proposal turns out to be a placeholder pending the outcome of the administration’s forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) or a harbinger that Biden intends to stick with the Trump plans remains to be seen.

The administration is requesting $43.2 billion in 2022 for the Defense and Energy departments to sustain and modernize US nuclear delivery systems and warheads and their supporting infrastructure. That includes $27.7 billion for the Pentagon and $15.5 billion for the Energy Department’s semiautonomous National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

The proposed spending on nuclear weapons constitutes about 5.7 percent of the total national defense request of $753 billion.

A direct comparison of the Biden submission to what President Donald Trump requested and Congress largely supported in fiscal year 2021 ($44.5 billion) and what Trump projected to request for 2022 ($45.9 billion) is difficult because the Biden proposal appears to reclassify how spending on nuclear command, control, and communications programs is counted, leading to a lower requested amount.

“The nuclear triad remains the bedrock of our national defense and strategic deterrence,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin told the Senate Armed Services Committee on June 10.

The 2022 budget “invests in nuclear modernization efforts, and the department will always seek to balance the best capability with the most cost-effective solution,” he added.

The budget request would notably continue the controversial Trump proposals to expand US nuclear capabilities. (See ACT, March 2018.) It includes $15 million to begin development of a new low-yield nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM), nearly $134 million for a new high-yield submarine-launched ballistic missile warhead (the W93) and associated aeroshell, $98.5 million for indefinite sustainment of the megaton-class B83-1 gravity bomb, and nearly $1.9 billion to build the capability to expand the production of plutonium pits, or cores, for nuclear warheads to 80 per year.

As with most new administrations, the Biden administration only had time for a quick reexamination of the fiscal year 2022 budget plans bequeathed by its predecessor. But the Pentagon did review some nuclear weapons programs, notably the Trump plans for a new low-yield submarine-launched ballistic missile warhead variant, known as the W76-2, and the new nuclear-armed SLCM. (See ACT, April 2021.)

The Navy began fielding the W76-2 in late 2019. (See ACT, March 2020.) The new cruise missile is undergoing an analysis of alternatives to determine possible options for the weapons system.

The future of the new cruise missile appears to be a controversial issue within the Pentagon. Despite the inclusion of funding for it in the budget request, guidance issued by acting Navy Secretary Thomas Harker on June 4 called on the service not to fund the weapons system in fiscal year 2023.

The budget request would also sustain plans that began during the Obama administration to replace long-range delivery systems for all three legs of the nuclear triad.

Three of these programs — the long-range standoff missile program for a new fleet of air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs), the Columbia-class program for a new fleet of ballistic missile submarines, and the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent program for a new fleet of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) — are slated to receive altogether a nearly 15 percent increase above what the Trump administration was planning to request in 2022.

The proposed growth in spending on nuclear weapons continues to force difficult choices for the Pentagon as to what other priorities must be cut back, especially at a time when military budgets are flat. Overall, the administration is seeking $753 billion for national defense programs in 2022, an increase of 1.7 percent from 2021 but a 0.8 percent decrease from the Trump inflation growth projection for 2022 of $759 billion.

Rear Adm. John Gumbleton, the Navy’s budget director, told reporters on May 28 that the service’s decision to buy one instead of two new destroyers “was absolutely an affordability question, where the goal of the department was to balance the first priority, which was investment in Columbia[-class submarine] recapitalization.”

The administration’s request of about $15.5 billion for nuclear weapons activities at the NNSA is an increase of $139 million above the 2021 level appropriated by Congress, but a decrease of about $460 million from the Trump projection of $15.9 billion for 2022.

The request for NNSA weapons activities is the first decrease from a prior year request since fiscal year 2013 and from a prior year projection since fiscal year 2016, albeit from a much larger baseline. Last year, Congress provided approximately $15.4 billion, a mammoth increase of $2.9 billion above the fiscal year 2020 appropriation. (See ACT, January/February 2020.)

In addition to funding the new warhead and facility projects first proposed by Trump, the request also keeps on track programs for the B61-12 gravity bomb, W87-1 ICBM, and W80-4 ALCM warhead upgrade.

The budget request would seem to be inconsistent with statements Biden made during the campaign to adjust Trump’s spending plans.

Biden told the Council for a Livable World in responses to a 2019 candidate questionnaire that the United States “does not need new nuclear weapons” and that his “administration will work to maintain a strong, credible deterrent while reducing our reliance and excessive expenditure on nuclear weapons.”

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) expressed concern that the budget request “expands almost every nuclear [weapons] program proposed by the previous administration” at a June 9 hearing on the budget request with acting Office of Management and Budget Director Shalanda Young.

Young said that as the administration begins the NPR process, Biden “remains committed to taking steps to reduce the role of nuclear weapons.” She added, “So you see a continuation of a program but [it’s] certainly subject to what [the NPR process] will yield out.”

Austin said that process will begin “very shortly,” and other administration officials have indicated it will be closely tied to a larger Pentagon defense strategy review. It remains to be seen, however, whether the review will be a stand-alone review, as past ones have been, or subsumed within an integrated deterrence review that also addresses missile defense, space, and cyberspace issues.

Sen. Deb Fischer (R-Neb.), the ranking member on the Senate Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee, on June 10 echoed other Republicans when she lauded the request for prioritizing nuclear modernization and keeping the programs to recapitalize the nuclear triad “on track.”

But she and other Republican lawmakers expressed concern about reports that the Navy might cancel the SLCM program prior to the commencement of the NPR process.

“We have serious questions for senior Pentagon leaders on this reported decision and how it was reached,” Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.), the ranking member on the House Armed Services Committee, and Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.), the ranking member on the Senate Armed Services Committee, said in a joint statement June 9.

Austin told the Senate Armed Services Committee that the memo was “predecisional” and that the fate of the weapons system would be determined by the administration’s review.

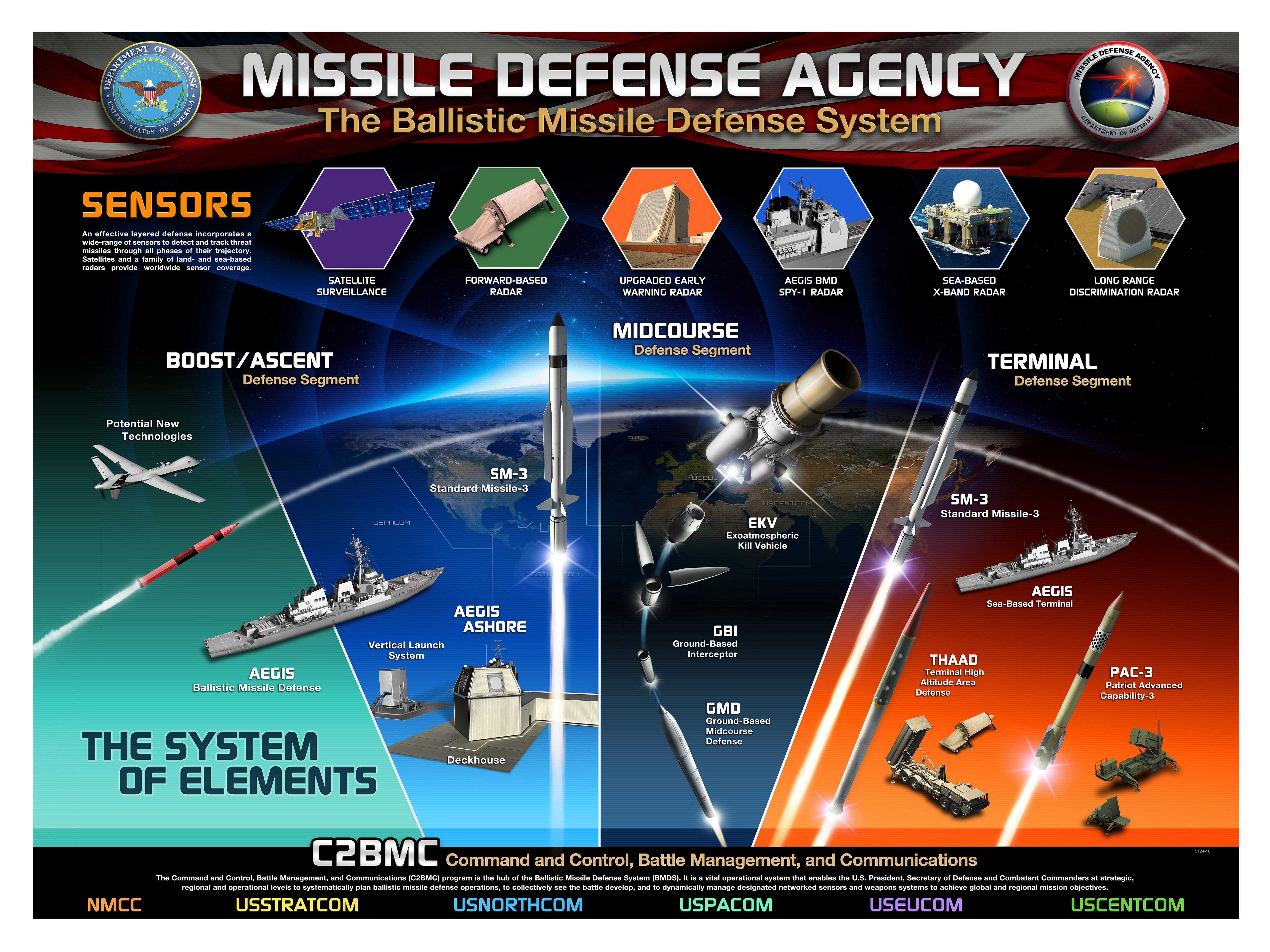

The Missile Defense Agency has plans for an elaborate layered homeland missile defense system but questions abound. (Illustration by the Missile Defense Agency)

Trump-Era Missile Defense Spending Continues

Kingston Reif / Arms Control Today

(July/August 2021 Issue) — The Biden administration’s fiscal year 2022 budget request would continue the Trump administration’s plans for missile defense, including a controversial proposal to supplement US homeland missile defenses by modifying existing systems to defend against longer-range threats.

The administration is asking for $20.4 billion for missile defense programs in 2022. Of that amount, $8.9 billion would be for the Missile Defense Agency (MDA), $7.7 billion would be for non-MDA-related missile defense efforts such as early-warning sensors and the Patriot system, and $3.8 billion would be for nontraditional missile defense and left-of-launch activities such as conventional hypersonic weapons.

The MDA request of $8.9 billion would be a decrease of 18 percent from the fiscal year 2021 level of $10.5 billion appropriated by Congress, but is similar to the roughly $9 billion the Trump administration was planning to request. (See ACT, January/February 2021.)

The MDA is asking for a total of $225 million for the layered homeland missile defense approach to adapt the Aegis missile defense system and the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system, designed to defeat short- and intermediate-range missiles, to intercept limited intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) threats.

Of that amount, $99 million would be for the Aegis system to “support a phased delivery of operational capability” to supplement the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system based in Alaska and California. The request also contains $65 million to “demonstrate THAAD capabilities for regional and homeland applications.”

The additional funds for layered homeland defense would support modeling and simulation and coordination of command-and-control activities.

The MDA requested $274 million for layered homeland missile defense in 2021. But Congress poured cold water on the proposal and provided $49 million only for limited concept studies, a decrease of $225 million from the budget request. (See ACT, January/February 2021.)

The skepticism from Congress came on the heels of a successful first intercept test of the Aegis Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) Block IIA missile against an ICBM target on Nov. 17. (See ACT, December 2020.)

But a report published in April by the Government Accountability Office said the test “was not an operational test…and it was executed under highly favorable conditions.” The report raised other concerns about the feasibility of the layered homeland missile defense approach.

Vice Adm. Jon Hill, the director of the MDA, suggested to reporters on May 28 that the layered homeland defense approach may no longer be as high of a priority for the agency.

“[T]here are some very serious policy implications” regarding the approach, he said, “and so we want to make sure that we get the policy angles right.”

“We want to make sure that it’s still a need” for the US Northern Command, Hill said, given planned upgrades funded in the budget to improve the capacity of the existing GMD system, which has been plagued by development problems, testing failures, and reliability issues.

The GMD system would receive $745 million in research and development funding in the budget request.

The request also includes $926 million for development of the new Next Generation Interceptor (NGI). An independent Defense Department cost estimate published in April put the estimated cost of the interceptor at $18 billion over its lifetime. (See ACT, June 2021.)

The department plans to supplement the existing 44 ground-based interceptors with 20 of the new interceptors beginning not later than 2028 to bring the fleet total to 64. The budget request would continue to fund a service life extension program for the existing interceptors to keep them viable until the NGI is fielded.

The MDA is seeking $248 million to develop the capability to defend against new hypersonic missile threats.

The Biden administration is planning a review of US missile defense policy and programs. Leonor Tomero, the deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear and missile defense policy, told the Senate Armed Services Committee on June 9 that the Pentagon would start the review “in the next few weeks.”

Asked whether it would be a “standalone” review or integrated with a larger review of deterrence issues, Tomero said, “[T]hat decision has not been made yet.”

Biden to Speed Development of Hypersonic Weapons

Shannon Bugos / Arms Control Today

(July/August 2021 Issue) — The Biden administration’s fiscal year 2022 budget request would accelerate plans that began under the Trump administration to develop and field conventional hypersonic weapons to compete with Russia and China.

The Pentagon requested $3.8 billion for projects related to research and development of hypersonic weapons in the budget submission published on May 28, including two new hypersonic cruise missile programs for the Air Force and Navy.

The request also includes funding for initial procurement of the Air Force’s Advanced Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) system, the continued development of the Navy’s Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) program, the addition of the CPS to Zumwalt-class destroyers, and the procurement of additional batteries of the Army’s Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) system.

“This budget supports our efforts to…accelerate investments in cutting-edge capabilities that will define the future fight, such as hypersonics and long-range fires,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin told the Senate Armed Services Committee on June 10.

Michael White, principal director for hypersonic weapons in the office of the undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, said on June 2 that “we’ve really been very fortunate in having a new administration continue the momentum and step up and champion what we’re trying to do with delivering this war-fighting capability.” He emphasized the importance of this acceleration given that “our adversaries,” namely Russia and China, “have fielded capability today that we don’t have.”

The Air Force requested $238 million for continued R&D on the ARRW system, an air-launched hypersonic glide vehicle, a $40 million increase over the Trump administration’s projected request in last year’s budget documents. The request is nearly $150 million less than Congress’ fiscal year 2021 appropriation for R&D, the Air Force stated in its budget documents, “due to near program completion and transition to early operational capability” in 2022.

The service requested an additional $161 million for the system’s production and rapid fielding. The Air Force most recently conducted the first booster flight test of the system in April, but it failed. (See ACT, May 2021.)

The Air Force also asked for $200 million for the new Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile program to design, develop, and test “a prototype that will demonstrate the viability of a multi-mission weapon concept to be fielded as a long-range prompt strike capability.” The request was included as part of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative, which Congress created last year to boost deterrence against China in the Indo-Pacific region.

The Navy asked for $1.4 billion for the CPS program, an increase of about $600 million from last year’s appropriated amount and $70 million above the Trump administration’s projection. The Navy attributed the increase in part to the need to add the weapons system, which uses the common hypersonic glide body, to Zumwalt-class destroyers starting in fiscal year 2025.

The Navy is also seeking $57 million for its new Offensive Anti-Surface Warfare Increment II weapon, a high-speed, long-range, air-launched weapons system aimed at addressing “advanced threats from engagement distances allowing the Navy to operate in, and control, contested battle space in littoral waters and [anti-access and area denial] environments.”

The Army requested $412 million for the LRHW system, which also uses the common hypersonic glide body, for costs that include funding for additional LRHW batteries. That was a decrease of $114 million from the Trump administration’s projection, which the Biden administration attributed in part to reallocating funding to sdevelop ground-launched missile capabilities.

It is not clear what if any effects the proposed budget cut would have on the LRHW program.

The Army requested $286 million to develop a conventional, ground-launched, midrange missile capability. The service announced in November its selection of the Navy’s Standard Missile-6 (SM-6) and Tomahawk cruise missile to serve as the basis for the new capability. (See ACT, January/February 2021.) This effort “will leverage existing SM-6 and Tomahawk missiles for ground launch, to provide a responsive, highly accurate, deep strike capability designed to destroy high value, high payoff targets,” according to the Army’s budget documents.

Both the SM-6 and Tomahawk missiles would have been prohibited under the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, from which the United States withdrew in August 2019. (See ACT, September 2020.)

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.