Projection for Shanghai with an increase of 2 degrees Celsius. (Image: Climate Central)

How Rising Seas Could Change Life in China Forever

Ryan Gandolfo / That’s Mags

(July 23, 2021) — It’s 2096. A plane flies over the international metropolis of Shanghai, and 30,000 feet below is a city covered in blue – the Bund, nowhere to be found; Lujiazui, a financial district up to its knees in watery debt. The Huangpu river overflowed, drowning a city and washing away its historical roots.

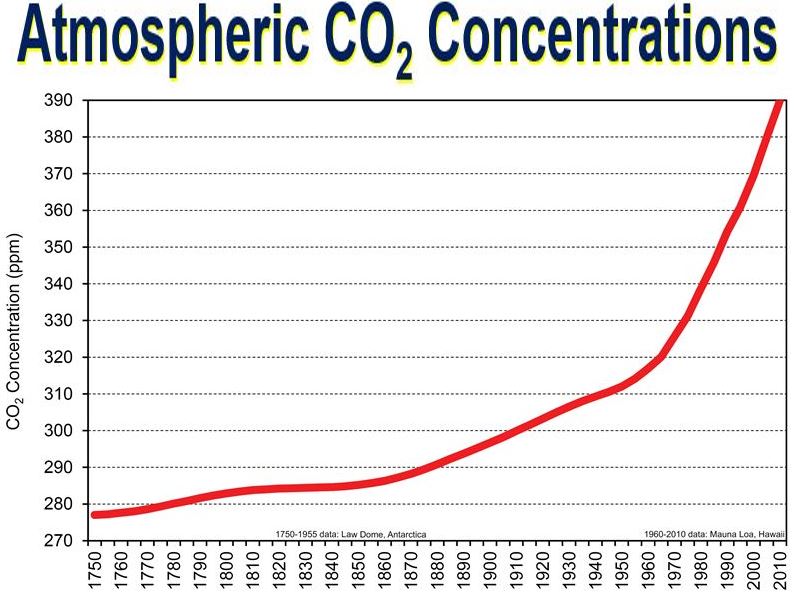

It’s a grim but increasingly realistic picture that the scientific community is painting for policymakers, politicians, businesspeople and the general public alike. So, how bad is it? Scientists are indicating that up to 630 million people may live on land below projected annual flood levels by 2100 if carbon emissions remain high. Lower emissions projections still show 190 million people worldwide could occupy land that’s projected to be below high tide lines by the end of the century. With the oceans absorbing over 90% of the heat from climate change, and continuing to warm at an accelerated rate, sea levels around the world are rising – a direct result of melting glaciers.

China has around 126,000 square kilometers of coastal area at or below 10 meters above sea level, making the country particularly vulnerable to rising tides. In addition to sea level rise, China faces frequent flooding and severe storms – a by-product of climate change – that decimate even non-coastal areas. So, how is the most populous nation on the planet responding to the threat of rising sea levels and flooding?

Sponge City project in China (Image: Turenscape)

Wayward Waters

Imagine the energy equivalent of five Hiroshima atom bombs being absorbed by the Earth’s oceans every second. Dr. Cheng Lijing made this data-based discovery when he and 13 other scientists across the world released a report titled ‘Record-Setting Ocean Warmth Continued in 2019’ this past January. The analysis highlighted reality: Climate change is making the world’s oceans warmer than ever in recorded history.

“To make it easier to understand, I did a calculation. The Hiroshima atom bomb exploded with an energy of about 63 trillion joules. The amount of heat we have put in the world’s oceans in the past 25 years equals to 3.6 billion Hiroshima atom bomb explosions,” declared Cheng, the lead paper author and associate professor with the International Center for Climate and Environmental Sciences at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

Cheng’s calculated approach is meant to provoke emotions and ignite change in a world where even seeing isn’t always believing, especially regarding climate change. After all, learning that the global ocean temperature average in 2019 was 0.075 degrees Celsius hotter than the historical average from 1980 to 2010 isn’t going to convey the most powerful message to your neighbor or colleague.

“It is the large number of people living in low-lying areas that makes the threat of coastal flooding caused by rising seas”

In October 2019, a study published in Nature Communications claimed that coastlines around the world are three times more exposed to extreme coastal water levels than previously thought, with Asia expected to receive the brunt of this aqua onslaught.

“It is the large number of people living in low-lying areas that makes the threat of coastal flooding caused by rising seas,” Dr. Scott Kulp shares with That’s. Serving as the senior computational scientist and senior developer for US-based Climate Central’s program on sea level rise, Kulp coauthored the Nature Communications article, which used a new method called coastal digital elevation model (CoastalDEM) to assess population exposure to sea level rise.

“China alone accounts for 18-32% of global extreme coastal water level,” the study says, forecasting that “China could see land now home to a total of 43 million people” below the high-tide level by 2100. The figure depends on different carbon emissions scenarios.

However, Chinese scientists have argued that the predictions by Kulp and his team are a bit of a stretch. “The sea level is not rising that fast,” Zhang Zhiqiang, a deputy director of the National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation, told state-run newspaper Global Times after the article was published.

But despite disagreeing over how fast ocean levels are rising, the Chinese scientific community also acknowledge the immense impact that climate change, rising sea levels and severe flooding can have on the Middle Kingdom. The country’s ‘Third National Climate Change Assessment Report,’ published in 2015, said China’s coastal seas rose 2.9 millimeters more than the global average each year from 1980 to 2012. The study also notes that for every 1 centimeter the sea level rises, it could push the coastline back at least 10 meters – roughly the length of a London double-decker bus.

“The long-term cumulative effect of sea level rise include loss of tidal flats, low-land flooding and ecological system damage, as well as storm surge, coastal erosion and salinity intrusion,” says Guo Hongyu, a project manager for China-based Greenovation Hub. When we ask Guo which regions in China are most at risk, she tells us that the sea level rise in China’s coastal areas has caused storm surge and flooding to be more severe, with Zhejiang province hit the hardest. She notes that estuaries of the Yangtze River, Qiantang River and the Pearl River all have increasing salinity levels. “Hebei, Guangxi and Hainan provinces have serious coastal erosion, and Liaoning province has a wider range of salinity intrusion,” she adds.

To combat rising sea levels, countries have invested in coastal defense infrastructure like seawalls and levees to protect coastal communities and economic hubs, Kulp tells us. He adds that by using flood projections, as seen in the analysis papers Climate Central has published, new developments and infrastructure can be built away from areas vulnerable to flooding.

Shanghai, a low-lying metropolis 3-5 meters above sea level and flanked on three sides by Hangzhou Bay, the Yangtze River estuary and the East China Sea, has built 520 kilometers of protective seawall to reduce rising sea exposure, according to the World Economic Forum. However, half of the city is still at risk of being flooded by 2100 due to the impact of land subsidence. This puts the Chinese mainland’s biggest economy in dangerous territory if high levels of carbon emissions continue and infrastructure remains the same.

Down in the economic powerhouse of Guangdong, the picture is equally grim. A February 2020 analysis by research firm Verisk Maplecroft notes that about one fifth of Guangzhou’s urban area is considered at high or extreme risk, according to the Sea Level Rise Index. In the Greater Bay Area, over 3,000 kilometers of sea defenses have been constructed, however the protection will be rendered less effective if global sea level rise reaches 30 centimeters.

So, with some of China’s biggest cities addressing sea level rise and flooding with measures that could prove futile in the latter half of the century, what alternatives are there for a flood-free future in the PRC?

A stormwater park (Image:Turenscape)

Gray to Green Infrastructure

The industrial revolution has played a fundamental role in shaping the world’s landscape today. But the accelerated economic growth and technological innovation that has turned cities around the world into concrete jungles has also come with a concerning environmental toll.

Award-winning landscape architect Dr. Yu Kongjian has been addressing modern urban infrastructure issues for the past 22 years with Beijing-based architectural design firm Turenscape.

The Harvard-educated design trailblazer is most famous for his lead role in ‘sponge city’ projects – an infrastructure initiative designed to create permeable water systems to prevent flooding and replenish our water supply. Its mission is aimed at utilizing nature’s strengths to optimize water use and other water-related urban issues.

“The modern city is totally dependent on industrial technology, we call it gray infrastructure, with steel pipes and pumps, among other industrial products. We know that current cities cannot solve the [water] problem, so we need an alternative,” Yu tells us over the phone from Beijing. “Where is the alternative?”

On July 21, 2012, China’s capital city experienced its heaviest rains on record, with at least 77 dead following catastrophic flooding. The severe storms may have served as a wake-up call for authorities to address severe flooding, with a slew of measures released to help address the issue. “The issue became very urgent, with President Xi Jinping calling for the development of sponge city projects [in 2014]. The Central Government and Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development formed a sponge city national committee and 30 Chinese cities were named trial cities,” Yu recalls.

One of the early sponge city projects by Yu and his team was on the southern island of Hainan – known for its monsoon climate. In Sanya, Turenscape carried out a massive mangrove restoration project to increase flood resilience. “Sea level rise in Haikou and Sanya is very obvious. We used mangroves in Sanya and restored them along the river and bay area so that sea level rise would be mitigated,” says Yu. “It’s the idea that sponge city is more resilient than gray infrastructure.”

“Green infrastructure and sponge cities are resilient and adapt to the fluctuation of water and are floodable”

A similar project was carried out along Haikou’s 23-kilometer-long Meishe River, which transformed a concrete-built drainage system to an ecological infrastructure project that united the river once again with all its tributaries, wetlands and green spaces to divert storm water from sewage flow.

Sponge City project in Haikou (Image: Turenscape)

In Shanghai, a city that is particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels, a sponge city project was constructed in Houtan Park. Located along the Huangpu river, the area was reconstructed from a landfill for industrial parts to a green space in 2010 around the time of the Shanghai Expo. Today, Houtan Park offers ecological services such as food production, flood control and water treatment. Field testing of the wetland indicated 2,400 cubic meters of water were treated each day for non-potable uses – saving a substantial amount of money compared with conventional water treatment.

Sponge city projects span from coastal areas to inland cities like Wuhan, with each project addressing local water-related issues. While sea level rise is a major concern, the more immediate task at hand seems to be mitigating severe flooding in certain Chinese regions, such as Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou and the Yangtze River Delta.

Since last month, at least 150 people have died and around 1.8 million people have been evacuated, according to the Ministry of Emergency Management. Direct losses attributed to flooding are estimated at over RMB49 billion.

Last month, 110 rivers recorded dangerously high water levels across eight provincial-level regions during the period of heavy rain.

Yu sees China’s current gray infrastructure as unsuitable to handle increasingly volatile weather. “Green infrastructure and sponge cities are resilient and adapt to the fluctuation of water and are floodable,” he says, noting cities prone to monsoons benefit greatly from these projects.

Sea the Future

While sponge cities have proven effective in both mitigating sea level rise in Hainan and controlling flooding in regions like the Yangtze River Delta, Yu will tell you sponge cities are not the only solution. “Since sea level rise is caused by global warming, it’s a global issue and we have to understand, adapt and mitigate. You have to know how to use less energy, less materials and reduce carbon emissions – that’s the big picture,” Yu tells us, adding, “Sponge cities can only solve the local problems. But the concept is there, so if we can mitigate carbon emissions then that will help [stop the oceans] from rising. But if the sea level rises six meters [due to global warming] then even sponge cities will not work.”

Guo echoes similar remarks, saying that sponge cities “help cities to deal with flooding issues, and enhance the adaptation abilities to sea level rise and flooding,” but makes the point that “to mitigate sea level rise and related impacts relies on the climate mitigation efforts by the state and non-state actors in China and around the world.”

As of now, Yu certainly has China’s attention. He shared with us an even bigger plan to put the whole country on a more sustainable path – ‘sponge land.’ Yu describes China’s water system like a human body, saying “You cannot fix one problem and forget about the others. Nature is biological, ecological, it’s a living thing.”

His sponge land plan will use geographic information system (GIS) and satellite imagery to track changes in China’s landscape and pinpoint priority areas where green infrastructure projects will have a profound impact. Niall Kirkwood, a professor of landscape architecture and technology at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, says Yu’s approach is like “applying acupuncture to the human body,” as cited by Scientific American.

Yu would like to replace centralized systems such as the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River, which wreaks havoc on surrounding ecosystems, and devise a decentralized way to better distribute water to farms, townships and other water-deprived dwellings. “When the Yangtze River floods, it’s stupid to try to stop it. You have to think about how you can store water. If we can do that, we’ll have a solution.”

“Rising seas are already amplifying coastal flooding during storms, but even then, concerns fade after the water recedes, and many rebuild in places that will only become more vulnerable in the future.”

Whether it’s sponge cities or sponge land, Yu’s goal to transition away from gray to green infrastructure is a shift that will require plenty of support. While the government has provided a helping hand in providing funding for these projects, people also need to play an integral part.

The daunting challenge, especially for residents in coastal cities, is to sacrifice a comfortable lifestyle for a more sustainable one, as some tend to write-off the implications of climate change.

“Rising seas are already amplifying coastal flooding during storms, but even then, concerns fade after the water recedes, and many rebuild in places that will only become more vulnerable in the future,” Kulp tells us. He makes the point that arguably the biggest challenge confronting scientists and community leaders is conveying the severity of sea level rise and its impact on coastal cities.

Kulp’s work with Climate Central has included striking visuals to further drive home the point. “Government agencies and officials, planners and media professionals tell us that providing diverse ways to explain the threat of sea level rise and to visualize its impacts helps them to understand the risks and communicate them to others.”

Guo shares that promoting civil engagement and international policy exchanges in the decision-making process could have an important role in addressing these challenges. She calls for China to be more forthcoming in sharing its experiences to other developing countries to build an “ocean ecological civilization.”

Aside from sponge cities and sponge land, Yu recently started a separate initiative called Wangshan Life, which embraces a nature-based lifestyle.

If you were to visit Yu’s Beijing duplex, you’d find a quintessential eco-home. His roof recycles storm water for reuse, there’s a vibrant veggie garden and porous limestone walls that cool the house so no air-conditioning is needed.

“After practicing [this lifestyle] for 20 years, I’ve noticed that we have no way to change the world unless we change our lifestyle. How can we live in a house without air-conditioning, how can we commute without driving … we have to live green, we have to be able to protect the environment while still enjoying life and harvesting the ecosystem,” he says, mentioning several testing grounds, including one in Huangshan, Anhui province, where Wangshan Life integrates education, arts and organic food and farming.

But will people be able to adjust their current industrialized lives for a more sustainable future? The answer may depend on when the ‘floodgates’ open.

This article was originally published in July 2020. Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.