Support for Troops in Kept Criticism Muted.

The Cost of Our Quiet Was Too High

Courtland Milloy / Washington Post

(September 14, 2021) — During 20 years of writing intermittently about the war in Afghanistan and the war in Iraq soon after, I encountered a dilemma: how to honor the warriors without honoring the wars.

I have met and corresponded with people who lost loved ones in combat or were seriously injured themselves. Nearly all of them believed that the United States was fighting to defend American freedom and democracy in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

To suggest, as I have on several occasions, that warmongering based on lies and profiteering got us nowhere, led to recriminations from people I was not prepared to argue with.

On Sept. 30, 2001, The Washington Post published a poll that showed only 2 of every 10 Americans opposed military action, even if it led to war. I wrote a column taking sides with the peaceniks, which drew a complaint from Stephen Push of Great Falls, Va.

“My wife was murdered aboard American Airlines Flight 77, so I have as much reason as anyone to want vengeance,” Push wrote. “But I support this war because I am certain that large-scale attacks will continue as long as terrorist organizations have safe harbors in places such as Afghanistan.”

Now the war in Afghanistan is finally over. And after 20 years, more than 243,000 war dead (mostly Afghan civilians but also 2,324 US military and 4,007 US contractors) and who knows how many trillions of taxpayer dollars, the same people who were giving safe harbor to terrorists before the war are back in charge again.

I certainly did not intend to cause Push or his family more discomfort. But I wonder if it was even possible to express condolences to those who died on 9/11, to honor those who served in combat, and still criticize the war in terms strong enough to have brought the madness to an end much earlier.

(Efforts to reach Push to see if his view had remained steadfast were unsuccessful.)

On Monday, the William D. Hartung Center for International Policy at Brown University released a report titled “Profits of War: Corporate Beneficiaries of the Post-9/11 Pentagon Spending Surge.”

“Since the start of the war in Afghanistan, Pentagon spending has totaled over $14 trillion, one-third to one-half of which went to defense contractors,” the report said. “Some of these corporations earned profits that are widely considered legitimate. Other profits were the consequence of questionable or corrupt business practices that amount to waste, fraud, abuse, price-gouging or profiteering.”

The problem with having so much profit in war, the report said, is that it can “contradict the goal of having the US lead with diplomacy in seeking to resolve conflicts.”

In other words, greed can prolong a war.

Still, it seems more fashionable these days to criticize how the war in Afghanistan ended than take a hard look at the role of money in keeping an ill-conceived conflict going.

Over the years, I would sometimes quote the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Kofi Annan and other peace advocates. Some readers would respond with quotes from the Bible, “an eye for an eye” being a favorite. I wrote a retort to that, ending a column with: “And everybody ends up blind.”

Mark Felipe of Arlington, Va., took particular offense.

“As someone who works in the Pentagon and was in that building on Sept. 11, I found Mr. Milloy’s statements an insult to the memories of those who lost their lives in the attacks,” Felipe wrote in a Letter to the Editor. “I share his hope that the US response will be proportional and just. But I would point out . . . that the United States did not ask for this war.”

No, the United States did not ask for the war in Afghanistan, but it certainly embraced it — and one in Iraq for good measure.

The war in Afghanistan began with a commercial-style promotional for a “shock and awe” campaign that would feature the “mother of all bombs.” This monster explosive was advertised as second only to a nuclear bomb in destructive power.

But when it detonated on some mountainside in Afghanistan, all we saw on TV was dust. We may have been shocked, but no one was awed.

Then another war was started in Iraq where you could actually see things get blown up. Never mind that Iraq had nothing to do with the 9/11 attacks. An Iraqi expatriate code-named “Curveball” supposedly told Western intelligence officials that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. But by 2007, the search for WMDs had ended. None had been found, Because there were none. Curveball admitted that he had made the whole thing up.

And yet, the war continued — with little opposition in the United States.

(I wasn’t able to reach Mr. Felipe to get his current take.)

What followed were warnings that we were at risk for another attack. Politicians began making a mockery of the color-coded terrorism alert system put in place after the terrorist attacks,raising the threat level and stirring up fears.And it always seemed to happen in advance of an election or whenever it seemed the public began to question what was going on.

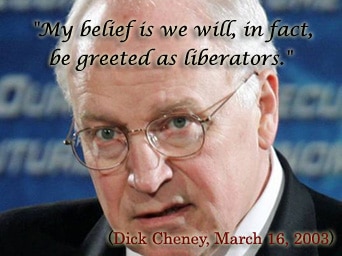

In February 2009, former vice president Dick Cheney began warning of a “high probability” that terrorists would attempt a catastrophic nuclear or biological attack in coming years, and said he feared that Obama administration policies would make it more likely that the attempt would succeed.

Cheney’s claims were widely reported, but mostly uncritically. He gave no reason or evidence for making such a statement. There was no attack. But the next year, there was a midterm election and exploiting myriad fears paid off: Republicans gained 63 seats in the House of Representatives, six Senate seats and six governor’s mansions.

A lot of things were done in the name of those untouchable wars that had nothing to do with defending anybody’s freedom.

And none of us asked for it.

At what was then the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in 2007, I met Michael Sparling of Port Huron, Mich., whose son Joshua had lost a leg to a makeshift bomb while on patrol in Iraq. Soldiers had gone to war ill-equipped and poorly protected. At least 18 military personnel in several bases in Iraq were killed by electrocution beginning in 2004 due to faulty electrical installations around showers and other living facilities, according to the Brown University report.

So much for all those trillions of dollars on quality construction.

I had asked Sparling what he thought about a Republican senator’s reported concession that the Iraq War strategy was not going well.

“If we start questioning the war, what does that say to our soldiers?” Sparling replied. “If people don’t agree with the war effort, the least they can do is keep their mouths shut.”

(Mr. Sparling died in 2016.)

But what America did for 20 long years was pretty much keep its mouth shut. Maybe someone will figure out how to speak out against war while patting our warriors on the back.

Or we could just not have wars.

Courtland Milloy is a local columnist for The Washington Post, where he has worked since 1975. He has covered crime and politics in the District and demographic changes in Prince George’s County, Md. He has also written for The Post’s Style and Foreign sections.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.