With the Afghan War Ended, America Can

Start Bring Troops Home From the Middle East

Eugene Gholz / The Quincy Institute on Responsible Statecraft

Executive Summary

(June 24, 2021) — US interests in the Middle East are often defined expansively, contributing to an overinflation of the perceived need for a large US military footprint. While justifications like countering terrorism, defending Israel, preventing nuclear proliferation, preserving stability, and protecting human rights deserve consideration, none merit the current level of US troops in the region; in some cases, the presence of the US military actually undermines these concerns.

Quincy Institute paper No. 2 asserted that the core US interests in the Middle East are protecting the United States from attack and facilitating the free flow of global commerce. These interests generate the following two primary objectives for the US military in the Middle East: to prevent the establishment of a regional hegemon and to protect the flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz.

The United States has no compelling military need to keep a permanent troop presence in the Middle East.

This raises the following questions: Does any country in the Middle East have the capability to achieve either of these objectives, or is any country within near-term striking distance of having such capability? What actions would the US military need to take to tip the balance of capabilities against an adversary seeking either regional hegemony or to close the Strait?

Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Turkey Could Vie for Middle East Hegemony…

The four possible contenders for regional hegemony are Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. To achieve the status of military hegemon, one of these states would have to have the capacity to knock out at least two of the others. To achieve this would require their army to possess at least five core capabilities:

1) logistics capacity to supply an advancing army;

2) ability to defend moving troops;

3) ability to respond to unforeseen circumstances;

4) ability to execute complex combined arms maneuvers on the offensive; and 5) ability to maintain control of captured territory.

… But None of Them Would Succeed

None of the four potential contenders in the Middle East has the requisite capabilities, and none has the plausible potential to rapidly acquire these capabilities in a way that would give it a relative advantage over its opponents.

… Nor Can They Close the Strait of Hormuz

Completely blocking the exit from the Persian Gulf would be a difficult task for any Middle Eastern military: An attacker would need to routinely hit and disable approximately 10 oil tankers each day, requiring multiple successful strikes per ship, firing roughly 50 missiles per day. The attacker would have to keep its forces alive and operational in the face of defenders’ efforts to prevent the attacks. Iran is the state that has threatened to close the Strait, yet it lacks the military capacity necessary to do so. Perhaps the greatest contribution that the United States could make to the continuing safe transit of oil through the Strait of Hormuz is to step back from the brink of conflict with Iran.

Russia and China Aren’t So Foolish as to Repeat Our Mistakes

Despite alarmism about the possibility of Russia or China making a bid for regional hegemony in the Middle East, neither has undertaken a concerted effort to do so. Russia’s presence in Syria is long-standing, and in general, Russia appears motivated to expand its role as a regional mediator; China is primarily interested in expanding its economic ties to the region. Both have observed US military misadventures in the region, and neither appears eager to repeat America’s mistakes. Most importantly, neither has the capability to overcome the obstacles that made US military operations in the region so difficult and costly — nor to potentially achieve a more expansive aim than the United States ever tried to achieve, namely establishing regional hegemony.

Fewer Arms Sales Would Help Sustain the Existing Multipolar Balance

To help protect the existing multipolar balance of power in the region, the United States should reduce arms sales, or at least prioritize the sale of defensive capacities, and offer strategic intelligence to all regional players, so any potential troop build up will be known in advance. If the United States needed to fight a war, it has the air and naval power to do so without peacetime presence or operations on the ground.

With Our Interests Safe, Americans Can Return Home

Given the extreme difficulties faced either by a would-be regional hegemon or an attempt to close the Strait of Hormuz, the United States has no compelling military need to keep a permanent troop presence in the Middle East. It should be the medium- to long-term objective of the United States to align its military presence with its strategic interests in the Middle East, beginning a responsible and timely drawdown of US forces in the region now.

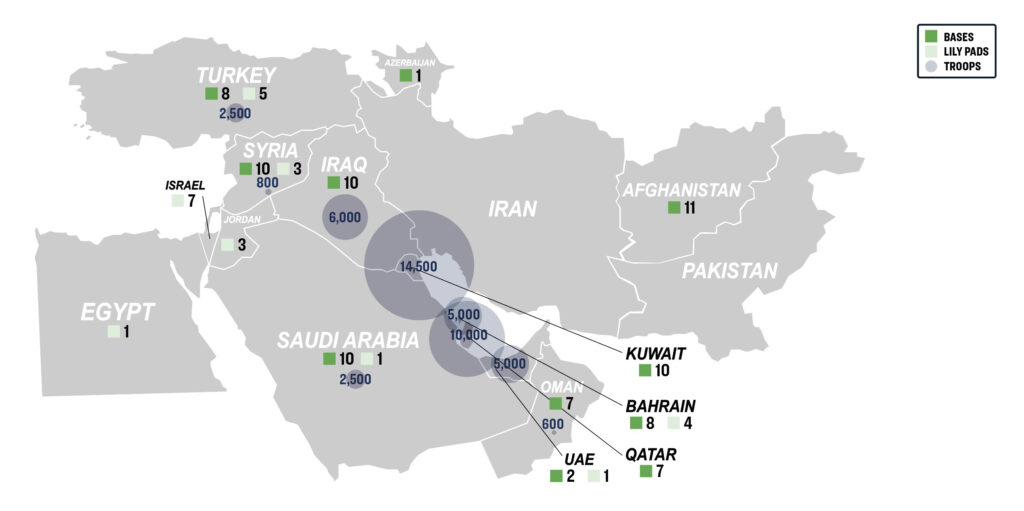

US Military bases throughout the Middle East.

Introduction

Why is it so difficult for the United States to bring its troops home from the Middle East? Three successive American Presidents — Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden — have pledged to end the post 9/11 wars and reunite US soldiers with their families. Yet, fulfilling that pledge has proven tougher than expected. Do US interests in the region require so much of the US military that full-scale withdrawals are not feasible?

Alternatively, do other factors, such as political and economic interests, inertia, or objections by strategic partners, prevent the United States from pursuing its first-order security interests? These questions have become all the more timely and important in light of a global review of American force posture announced by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin in February 2021.1

This paper argues that the United States has no compelling military need to keep a permanent troop presence in the Middle East. The two core US interests in the region — preventing a hostile hegemon and ensuring the free flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz — can be achieved without a permanent military presence. There are no plausible paths for an adversary, regional or extra-regional, to achieve a situation that would harm these core US interests.

No country can plausibly establish hegemony in the Middle East, nor can a regional power close the Strait of Hormuz and strangle the flow of oil. To the extent that the United States might need to intervene militarily, it would not need a permanent military presence in the region to do so.

While a full military withdrawal from the region is possible on military grounds, political and other factors render it infeasible in the short run. However, it should be the medium to long-term objective of the United States to align its military presence with its strategic interests in the Middle East by beginning a responsible and timely drawdown of US forces in the region.

Why the Current US Presence Is Militarily Unnecessary

True US interests in this region, as in any other region abroad, ultimately derive from the core national principles of preserving and advancing the security and well-being of the American people. In a previous Quincy Institute paper, Paul Pillar, Andrew Bacevich, Annelle Sheline, and Trita Parsi argued that US objectives in the Middle East — the region-specific interests that make the ultimate US goals concrete — are limited to preventing the emergence of a regional hegemon and helping to maintain the flow of global trade.2 This paper argues that neither warrants a major US military presence in the Middle East, let alone American pursuit of regional military dominance.

US Military Installations in South and West Asia, 2020

Source: Professor David Vine

Base: Greater than 10 acres in area or $10 million in value

Lily pad/Small base: Less than 10 acres in area or $10 million in value

US Funded: US personnel may have access to or use facilities paid for in part or fully by the US taxpayers

The Washington foreign policy establishment tends to adopt an expansive definition of US interests in the Middle East. Overreach in defining interests goes a long way in explaining America’s military overextension in the region. Nevertheless, even accepting a broad definition of US interests would still not warrant a permanent US military presence in the Middle East.

This section briefly considers and rejects a range of additional potential US interests in the Middle East, leaving the two core interests identified in the earlier Quincy Institute report as the ones that should be considered in determining US military force posture and missions in the region.

Terrorism

The threat of terrorism is frequently invoked as a justification for the US military to maintain a presence in countries from Afghanistan to Syria. Yet after twenty years of fighting a global war on terror (GWOT), the evidence is irrefutable: Militaries are ineffective at combating terrorism. Instead, preventing terrorism has significant parallels to preventing crime, in that it can never be fully eliminated but can be reduced through effective governance and policing activities.

In contrast, the presence of a foreign military force consistently generates both grievances and acts of violence that inspire additional acts of terrorism. Foreign military occupation in particular makes the threat of terrorism more acute.

The presence of a foreign military force

consistently generates both grievances and acts of violence

that inspire additional acts of terrorism.

Instead of repeating the failed strategies that followed 9/11, the United States should focus on preventing any major act of foreign terrorism in domestic territory, something that it has successfully accomplished since 2001. The full elimination of all terrorist threats would require a level of state authoritarianism that Americans would find intolerable and anathema to their values; instead, the security establishment has successfully eliminated some threats and continues to monitor others. Finally, if US leaders perceive the presence of a foreign terrorist threat, the US military has demonstrated its ability to eliminate targets without a significant troop presence on the ground.

Israel

America’s security commitment to Israel is often mentioned to justify the presence of the US military in the Middle East. Yet circumstances have shifted since Israel’s establishment, and decades of US support and partnership have provided Israel with a robust capacity to defend itself, including with nuclear weapons. The US project to empower Israel has been successful, and US military defense of Israel need not drive American strategy in the Middle East. In fact, the instability that the US military presence in the Middle East fuels may actually undermine Israel’s long-term security.

Nuclear non-proliferation

A third claim regarding the need for a persistent US presence in the region is to enforce nuclear non-proliferation, often specifically in reference to Iran. The reasoning behind this claim was always flawed, as it arguably has been the ongoing US military presence in the region that has driven Iran to feel it had no means of achieving security without acquiring nuclear deterrence.

Moreover, the presence of US troops has played no discernable role in dissuading Middle Eastern countries from acquiring nuclear weapons. It was not US military strikes that undermined possible Syrian or Iraqi nuclear programs, and Egypt did not decide to discontinue its nuclear program because of a US troop deployment.

Stability

Justifications for US military presence in the Middle East sometimes emphasize stability as a core US interest. In general, regional political stability is conducive to US interests — a more stable Middle East is less likely to threaten the core interests of preventing a hegemonic takeover and protecting essential trade. Yet, there is little to suggest that a permanent US troop presence is either necessary for stability or conducive to it.

Indeed, the United States’ implicit security guarantees to regional partners have in many instances fueled their reckless and destabilizing behavior due to their perception that the United States will come to their aid if they get into trouble. The Saudi war in Yemen is a case in point.

Human rights

The protection of human rights is often used as a justification for US military intervention, but there is no evidence to support the idea that a permanent troop presence in the Middle East deters human rights violations. On the contrary, mindful of the fact that many of America’s strategic partners in the region are some of the world’s most notorious human rights violators, it is more reasonable to conclude that the US military presence in the region has served to protect these regimes despite their human rights violations.

Moreover, when the United States has intervened militarily in order to prevent human rights abuses, the interventions themselves have generally caused massive human rights violations, as evidenced by the US interventions in Iraq and Libya.

Military Requirements to Protect Core US Interests

The Quincy Institute’s proposed strategy for the Middle East sets two goals for the US military: preventing establishment of regional hegemony through military conquest and maintaining the flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz to international markets. To decide what these goals ask the US military to do — what forces to acquire, how to train and exercise, and where they should be positioned in peacetime to deter and, if necessary, respond to threats — requires answering a series of questions for each goal:

What would it take for an adversary to bring about one of the undesirable conditions, assuming that an adversary desired to do so? Does any country in the Middle East have that capability, or is any country within near-term striking distance of having such capability? What actions would the US military need to take to tip the balance of capabilities against such an adversary? And what force structure and posture would best prepare the US military to thwart such an adversary, minimizing cost and risk and maximizing the visibility of the US capability, thereby creating the conditions for credible deterrence?3

To read the full report online, click here.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.