The Camera is the Rifle: An Interview With Oliver Stone

Dennis Bernstein / CounterPunch

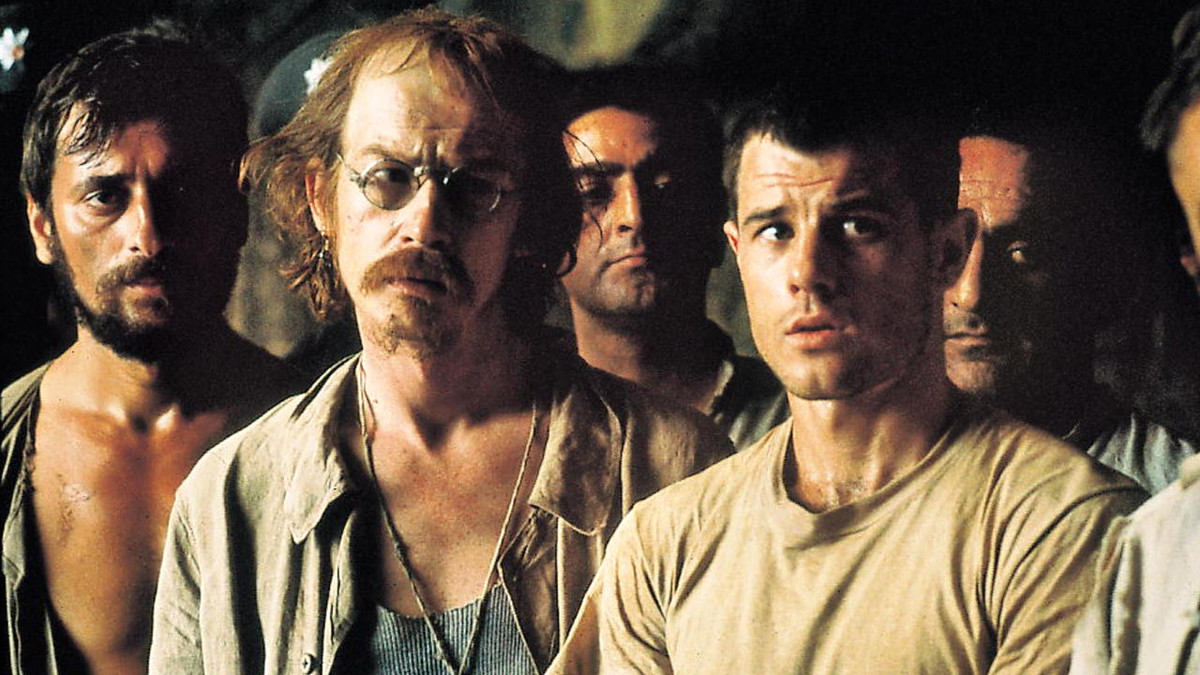

(September 24, 2021) — William Oliver Stone, the Legendary Filmmaker and multiple Oscar-winning writer and director of JFK and Born on the Fourth of July, has a powerful new memoir: Chasing the Light: Writing, Directing, and Surviving Platoon, Midnight Express, Scarface, Salvador, and the Movie Game. Stone is also poised to release a brand new documentary about the assassination of JFK.

Like most of Stone’s film work, Chasing the Light is up-close and personal. It’s a deep dive into his complicated New York childhood, his decision to volunteer for combat in Viet Nam, and his struggle to overcome a drug habit. Stone’s powerful new memoir confronts the struggles and up-hill battles behind the making of such films as Platoon, Midnight Express, and Scarface.

The memoir marks the multiple challenges that preceded Stone’s international success with Platoon, in 1986. Oliver Stone was wounded as an infantryman in Vietnam, and spent years writing unproduced scripts while driving taxis in New York, finally venturing westward to Los Angeles and a new life. Stone, now 73, recounts those formative years with in-the-moment details of the high and low moments of his life: We see meetings with Al Pacino over Stone’s scripts for Scarface, Platoon, and Born on the Fourth of July ; we see him harrowing demon of cocaine addiction following the failure of his first feature and then his auspicious comeback: I sat down for a interview with Stone late last week to talk about the memoir and his new soon to be released doc on JFK.

OS: I read your bio this morning. I see we did parallel each other to some degree. What year were you born?

DB: I was born in ’49. You’re a couple of years older than me. I dodged the draft. You enlisted, right? I remember sitting for the draft lottery, wondering if I would have to go to Canada or Nam?

OS: I don’t know. You’re one of those wimp-assed, fucking east coast people that didn’t want to go in the Army. I can’t understand you guys. I mean you saw the Vietnam War as a disaster. I didn’t at that time.

DB: Yes, Welcome, Oliver Stone, to Flashpoints. It’s good to have you with us.

OS: Nice to be back. I was on a couple of years ago.

DB: Yes, A couple of years after we’ve spoken, I believe we met at the late Robert Parry’s house, where you were given the Gary Webb Award. And we also were traveling the same ground there as well. It is good to have you back with us Oliver.

I found your autobiography both moving and compelling. So much about war and the aftermath. I remember one time when I got stung by a bee, I was about 11, and my father caught me going out the door with a can of Raid. And he says, “where you going?” And I said I got stung by a bee and I’m going to go kill a whole bunch of bees. And he said did I ever tell you the story about how a bee saved my life? And I said no. He says yeah.

Well I was in the ditches and we were taking a break and this bee started dive-bombing my dad. I think it was Sicily, the Battle of Bloody Ridge. And he said “So I got out of the trench and I went behind a tree to grab a smoke, and as soon as I got out of my hole there, a mortar hit and killed 9 of my best friends.” Then my dad made us some tea and sweetened it with a nice dollop of fresh honey from a beekeeper who was a regular in my dad’s cab.

OS: That sounds horrible.

DB: Soldier Dad said to me, “if I ever run into General Patton in a drug store or the candy store, “I will punch his ass out.”

I really want to start with what Martin Scorsese said to you in Films chool, that I think you found very moving and a life changer. And Scorsese said it in response to your first black and white, 16mm film. He said to you in response to your film, “The person who is making it is living it.” That was sort of your degree, wasn’t it? That was the real degree you got from college and your mantra all the way through.

OS: I’d say that was the highlight of my 2½ years at NYU. Martin — or Marty as we knew him then — was a very down-to-earth, but very smart and was very entertaining as a teacher. We were making films, very cheap films — black and white, 16mm, and editing them, writing them, starring in them, shooting them ourselves; it was mostly pretty amateur work. But this stood out to him, and usually we were into auto-critiquing like the Chinese cultural revolution. So usually you get a lot of criticism after you showed a film in class. It was a hard go-around. And he just shut it up right away. He said this is a film-maker, which I know was my diploma.

DB: Yes, really. And it was a film about war.

OS: It was about my returning to New York, yes.

DB: From the war.

OS: And my casting aside the medals, that’s right. It was about all the junk you wanted — the veteran has to lose the memories that he was carrying in order to move on with life.

DB: Now you made these three amazing films, of course Platoon was the first in a trilogy, and that was all about your experiences in Vietnam. And I found it very moving. Could you talk a little bit about — you talk about terminology like friendly fire. There are these terms that you learn in war. Talk a little bit about the language of war in the context of that Vietnam War.

OS: Well, I went in and I was a volunteer, and I was sent over as a replacement troop into a unit at the 25th Infantry, which had lost some men, and we were all replacements. And it was very factory-like in the sense that people didn’t want to get to know you too much, because we didn’t really — there was none of that wartime this-is-your-buddy stuff.

We all were trying to stay alive, and everyone was counting off the days until they had left. It was like working for a taxicab company, which I had done also. So it was a routine, and it was a tough routine. And sometimes it would work out that you would bond with somebody, but not necessarily.

I was talking about the three lies, the three biggest lies I witnessed in Vietnam, and I gradually learned them over the time I was there. Because a lot of guys were getting hurt by friendly fire, which is our own artillery, our own planes and our own fire — rifle fire, ground fire. There was a lot more of that than people thought there was, because were in the jungle in asymmetrical warfare, and sometimes people — stupid people — would shoot without knowing where they were shooting because they were thinking.

The problem with a lot of that war was that US troops when they get under fire, whether it’s in Afghanistan or Vietnam, they just open fire. They just fucking go crazy. It becomes like a mad minute, and that doesn’t work. You put out a lot of fire, and of course the idea is that you scare off or you stop the enemy from advancing. It’s ridiculous, and frankly kills a lot of people, as well as civilians; a lot of them were killed.

And that was the second thing I saw: a lot of civilian deaths. And when we say — we just don’t admit it. Because if you look at the casualty figures in Afghanistan, I’m sure you’re going to find a lot more than you know about US bombs killing Afghans. And I think that is one of the hidden facts of all wars; civilian deaths.

And the third I said about it was that the biggest lie of all was that we’re winning this war, which is what they told us all the time. It was we’re not losing; we’re winning; we’re kicking ass; look at the body counts. But then on the other hand, the more of them you killed — and of course they were inflated body counts because they included civilians — the more of them you killed, they always seemed to be replaced.

So who knows? It was Alice in Wonderland; the American strategy was nuts. Cleaning out villages and making them move to other villages that were supervised by corrupt, government troops; it was not a solution. And the people were caught between two different forces. Naturally a lot of us started to resent them because we thought they were helping the enemy. So this led to all kinds of problems. But the biggest problem of all was from the top down, the leadership; and it was military. It wasn’t political.

The military people that are hardcore will always tell you it’s politics and ended the war. And they’ll say the same thing about Afghanistan. But it’s not; it was just a shit situation in terms of military situation. And if you don’t want me to say shit, I can say it was just a hopeless situation in terms of the military.

DB: Thank you. You remember Pacifica and the seven dirty words, so we’ve got to be careful about that. So I’m thinking, when I — and I really enjoyed your reading of the book — I’m thinking that war really ends up being at the core of everything you do; even outside this trilogy that it has that deep impact. And one has to realize that so many young men come back wounded and never recover, and this becomes sort of the core experience. We used to make fun — my brother and I used to make fun of my father when he would keep retelling us the same war stories. You know, we sort of had them numbered and labeled. And we’d go ha-ha, and laugh behind his back. But this is at the core.

OS: A lot of veterans don’t talk about it, and they carry it inside. And I’m not so sure that’s very healthy either. I think by making those three films I was able to exorcise quite a bit of things that were inside me. As you know, I jumped around on all three subjects.

The second one was about another young man who came from a small town, not like me, and who came back to a small town paralyzed. Ron Kovic’s Born on the Fourth of July. So that’s a powerful story, I think, of pre-war/post-war, as well as war; there was quite a bit of action in that movie.

The third story was the Vietnamese peasant wives and their point of view. A woman who grew up in a village, and that’s a true story. She wrote a book, I optioned the book, Le Ly Hayslip. We called the film Heaven and Earth. And it’s, I feel, one of my best movies; but it’s kind of –

DB: Very powerful film.

OS: It came too early and it was about Asians. So I figured the American people were not interested in that side of the story.

DB: Well I live with one, and I get that perspective. Back to Ron Kovic; another place where our lives overlap. My mom — we grew up on the Lower East Side, but my mom took us out to a place called Massapequa. Have you heard of that town?

OS: Sure. Massapequa is where Ron was from. I was there.

DB: And when — I mean this was a big thing. My parents used to shop in the Bohack; I think that’s what the store was called.

OS: Oh yeah, Bohack. I remember Bohack.

DB: Where Ron Kovic grew up. And then I remember hearing Tom Paxton for the first time singing this song; I don’t know if you’ve ever heard it. Born on the Fourth of July. And it’s got — the refrain is “I was born on the fourth of July, no one more loyal than I. When my country said so, I was ready to go, I wish I had been left there to die.”

OS: Never heard it. I’ve never heard it.

DB: It’s powerful — you know, I was thinking when I was going to see the movie, your movie, I was thinking oh, that’s going to be the theme song. But then I thought to myself, no. Because he tells the whole story, the whole story is in the song; why do the movie? But the movie was a life-changer for me as well, and I’m sure for many young men who had survived that draft and that war.

OS: Yeah, although it’s not referred to, interestingly enough, as a war film, and it’s left off those lists; but I consider it a war film, very much so. Because it’s about what the boy was like before and what he was like after. And what the family situation is at home as well as abroad. So you know, I don’t know. Things get lost. I love Born on the Fourth of July; I think it’s one of my best films.

DB: I agree. And it’s sort of how the whole — one person in the family goes to war and the whole family goes to war. I’m remembering a film that came out of World War II; I think it was called The Best of Our Lives. Do you know that film? Was it The Best of Our Lives? Where he comes home and he –

OS: Oh, The Best Years of Our Lives, yes. That’s a classic from William Wyler, 1946. Frederick March. Three men came back from the war and each one had a different fate in his hometown.

DB: Yes, and I remember as a kid watching it.

OS: And it certainly was an inspiration for Born on the Fourth of July, certainly. I saw that film more than once. It’s a great film.

DB: And it really does show how you’re sending a whole family to war.

OS: It’s one of the most honest films I think Hollywood ever made. Because in that period, the American viewer was going very back towards the right wing, back towards the Republican era, and those films were no longer made after that. That film in fact almost got Wyler into the black lists; it came close. It’s an interesting story.

DB: Really. That is something. And again, it was powerful. I think in part it was in black and white, I believe.

OS: Yes.

DB: I guess that’s what they were using at that point. Or maybe somebody just chose to do it in black and white. But that also made it a very powerful film.

OS: Yeah.

DB: Could you talk a little bit about — I want to sort of backtrack a little bit and I want to talk a little bit about your family, your dad, your mom. Your dad was a Jewish businessman who worked on Wall Street — hence the film Wall Street — back to the person who is making it is living it. And your mom was sort of a — I don’t know. These days we’d say a party girl. But she was the entertainer. She was having parties; she was out there. Could you talk about you parents and how they influenced you?

OS: You called it an autobiography, but I’d call it more of a memoir; because it becomes subjective, highly subjective. And it’s about my relationship with the two parents. And because I was the only child, it was seen like a perfect family to me; a triangle that was working. And when it fell apart suddenly — and that was in 1962 when I was 15, 16, and I was at boarding school — and I was shocked to be told on the phone so coldly that the divorce — the marriage was over.

I mean it was like a 180° turn. And I was not consulted or anything, because it was going on and there was a lot of tension between the two that I knew nothing about. Which was kind of a shock to me, and a coming-of-age kind of thing where you’re 15 and you say well, it’s a whole other world that I’m in now. The parents separate and it’s no longer “a family”; there is no family anymore. And especially if you’re an only child it’s just — you’re all on your own now, basically. And that’s what happened to me. I ended up in those years kind of being very disturbed, and eventually going — I went to Vietnam twice.

But my mom was, what did you say, a party girl? Yes. But in those days that was not wrong. It was a woman of a certain means — if she had means — would not work. It was acceptable. No longer, but my mother of course was very supportive of the family, and of my father. And she thought she was contributing with her grace and her charm and her party-giving to his career as a broker. And she did. So there is an alliance, a partnership between the parents.

My father was, as depicted in the book, also a very strong man, like my mother; both very strong people. And I wrestled with my father when I came back from Vietnam because he was supporting the war. And he was an Eisenhower Republican, and a smart one; not stupid at all. He wrote about it for a while, and he wrote a monthly letter. But he had a view of the world that was very Republican.

It certainly influenced me and I was conservative. But it took me years to undo that; years to kind of see the real world the way it was devolving for me, not for him. He came out of The Depression; I can understand his feelings. And he was always very strongly anti-Roosevelt. So I had to learn my own — I had to figure it all out gradually as I was going along.

And so let’s say by my 30s — the book centers on the first 40 years. And when I was 30, I was very depressed. Nothing was working; my life was not working. And I wrote the book on the idea that I wanted to show younger people what it’s like growing up in that time period, and how because I had a dream about being a filmmaker, I achieved it finally. I achieved it against great odds; so many rejections of my material, including The Platoon.

More than once, it almost got made. But basically from my 1987, ’86, when I was 40 years old, I had broken through, and it was a tremendous overnight success. Platoon was amazing; it went around the world. Elizabeth Taylor was giving me an Academy Award; best picture, best director, it was a fairy tale. And you can’t end a book better than that. I mean you achieved the dream after so much rejection and pain that it means something so much more to you and it was very sweet.

So maybe the story should end there at the age of 40. But it doesn’t; there’s another story in this, it goes on. I have to write still; it’s another book I want to do.

DB: Another book. And what is it about film that you chose as your main medium for?

OS: Well because I had written a book before I left. I had written a novel when I was 19 years old, and it was very — partly out of that pain and that loneliness; the divorce and the isolation. The sense of separation from a family; a lot of pain. It came into this book, an autobiographical novel. Which was pretty amazing. It was published years later as A Child’s Night Dream in 1997 by St. Martin’s Press. Which was an interesting book; a lot of craziness in it.

Written by a 19-year-old really; it’s a 19-year old’s book. And I look back on it fondly. But it shows me — in other words, I was a writer. But when I came back from the Vietnam War, I no longer was satisfied with being a novelist. What I had seen was so visceral over there, and so in-your-face; six inches in front of your face. Your eyes, what you see and hear and smell. You have to become a 360°, full-contact person. And that’s not really what a novelist does. A novelist is very much in his head. You cannot be in your head in the field.

You have to be alert and you can’t be thinking these things. So you kind of achieve another kind of viscerality, which I can’t explain quite until you pick up a camera and you can relive it. The camera gives you that viscerality, that sense of being the rifle. The camera is the rifle; it shoots. And it shoots what you want it to shoot.

So I basically came back from the war as an infantry soldier, as a filmmaker; wanting to be a filmmaker, a wanna-be. And that’s where I learned how to make them at NYU gradually. It took me a few years to get to the place where I could have some success. My first success was at 30 with The Midnight Express. No, I’m sorry — yes. No, it was at 32 with Midnight Express, 33; after that 30. At 30 years old it looked –

DB: Yeah, that was in — you made that — and that actually won an Academy Award for best adapted screenplay.

OS: Yes, it did. After that I was in the business; I was accepted in the business, and it was up and down. The business has a thousand pitfalls, and I certainly go into some of them. And I think it’s very illuminating for younger people who want to pursue the arts to see this story and feel it.

DB: And pursue you did, courageously. You know the book; we’re talking about Chasing the Light; Writing, Directing and Surviving Platoon, Midnight Express. Scarface, Salvador and the Movie Game. And it opens up with you completing your first film, which is Salvador. You’re making it in Mexico. And I really want to ask you how you had the courage; how you could go forward in the face of having to deal with and juggle. Not only are you worrying about doing the film, but you’re worrying about having the whole thing pulled out from under you if you go over budget.

OS: Listen, Salvador was –

DB: How do you do that?

OS: How do you do it? You do it by learning. And learning — in Vietnam there was an expression: on the job, or learning on the job training; on the job training. You just do it. And that’s what happened. It was one of the worst nightmares you could ever have as a filmmaker. I could never survive it now. I was — I didn’t know better. But there was just no money; it was a dream from the beginning.

I pushed that dream. I wanted to make the film. It was about war in Central America. And I went down there with a crazy journalist who was a friend of mine who lived through some of these experiences, and I based the film on his story. But we were so — between our desire and our execution there was quite a bit of a problem, so it took — it was an insane story.

You have to read it to understand it. And an English company bailed us out. It was an English producer named John Daley who was taking chances in the 1980s, ’85, and he made both films. He made Platoon and Salvador. So without him it would not have made it. No American company would touch Salvador or Platoon. No American company would finance it, do you understand? That’s what’s really depressing. And it’s still going on.

.jpg)

DB: Why do you think that is?

OS: Well because they want to make money, and they thought that Stallone was the answer with his bullshit Rambo films. And Chuck Norris, the other guy who’s another right-winger, was perfect for the American people. It was what they wanted to hear, but it was not true. It was called Missing in Action and Chuck Norris made about three or four films about it, which was — that was the vogue. That was the vogue.

And by the time I came along I thought it was over. I put Platoon in the closet and I said forget it; they’ll never make it. It was almost made, but it never got made. And then I gave up, and out of the blue three or four years later John Daley committed to it and he came through. He came through on both films, and both films became hit successes for me. Huge hits; I mean certainly Platoon.

DB: Wow. And why did you make that film? Why El Salvador?

OS: Well because it was a great story. It was a great story about war. Central American war is a dirty, dirty, dirty story about America. The same kind of mindset that created Vietnam was involved in 1980. Salvador, in Honduras, in Guatemala and in Nicaragua. Remember the Nicaraguans were having a revolution, the Sandinista Revolution. And the American government took a strong stance against it because they thought it was Communistic.

Actually it was about land reform and making the lot of the poor in that country, or the people, most of the people, making it a better situation for them. But that’s not the way the American people saw it. So we supported dictators in those regions ever since; we always have. We want stability over any kind of uncertainty.

DB: You know the thing is it’s impossible to get that information out, in terms of the relationship that the US government has with for instance the death squads in El Salvador.

OS: It’s come out, but no one wants to listen. Yeah, we always support the death squads. And in Vietnam certainly there were death squads. Americans fought another war; it was a covert and a dirty war where we killed people. Peasants that were seen as progressive. And the same thing went on in Afghanistan. I mean you have no idea.

There’s this other — one sector is the military and then the other sector is what now becomes the contractor at war. Which is to say you have a contract and you go out and you do your dirty work for the government; and you kill a lot of people who are seen as oppositional.

I was joking with somebody the other day. I said yeah; the Americans should let all the Afghanis in who worked with them. That means all the bad guys too. The Americans have this picture of the people who worked with them as all these good guys. Some of them were. But a lot of them were bad-ass people who were getting — who were doing a lot of killing and a lot of spying, killing.

In other words, war is ugly. And we used everything we could to win that war. We used torture; we used all these sci-op techniques. It was very important for us to win the hearts and minds of the peasantry, which we never did; either in Vietnam or in Afghanistan.

DB: You say that it’s reported in the US, but not really. I don’t think in the United States your everyday, average citizen knew, for instance in El Salvador, that there was a guy named Roberto D’Aubuisson who once turned — told a German photographer that you Germans did the right thing; you killed all the Jews. Or drawing straws to shoot the archbishop through the voice during the eucharist. I don’t think –

OS: Plus there’s a whole dark side of the American story. I mean it’s true in every country in South America since we’ve had dictators everywhere. And wars; Argentina there were death squads all over the place, and in Brazil earlier than that in the ‘60s, and in of course Chile in ’71, or ’73 rather.

DB: ’73, right. September 11th; 9/11. When I saw the twin towers going down, I thought the Chileans are taking revenge. It’s September 11th, and the United States with the CIA overthrew the duly elected government of Allende.

OS: And not only that, we cooperated with the new government in picking out — I mean lists of people to be examined an often thrown out of helicopters or tortured. In other words as we did in Indonesia. Everywhere we go, we do this. There’s no fun to have in this story at all.

DB: Right. And I think that’s part of the gift of your work, Oliver Stone, that you put in film what we can’t, what we journalists can’t seem to get people to understand in terms of where your tax dollars are going. I’m just reading that I think they’re upping the defense budget big time. Meanwhile they’re hassling over whether they want to have a budget that’s going to support human life and people having a place to live and hospitals.

OS: Yeah, I know. And we have to bring all the people that we owe; our collaborators in those countries. They’ve been kicked out; they can’t work there; they’ll be killed. So they come and move to the United States. I suggest that they move to Miami and join the other; all the people that work with the Cuban exiles. Some of them are murderers and torturers, and they blow up anything. They’ve done it so many times. They go back into South America and they help the Chileans and they help the Argentinians with their dirty wars. In other words, we have a whole mini population of murderers and torturers in our country who were given sanctuary here.

Oh by the way, you have to include the South Vietnamese who did it over there, and they are moved into Orange County and here in Los Angeles. So we have communities of that.

DB: And then the history is rewritten. I mean we love the fact that –

OS: They become the victims. They become the people who got screwed, so to speak.

DB: There was a Vietnamese writer from South Vietnam, who wrote this — sort or rewrote history. It was about worshiping the ladder that was allowing the last Vietnamese to escape the Communists in the last helicopter.

OS: Propaganda.

DB: Propaganda; a lot of propaganda. You do say in this memoir that it’s really about — where is it that I wanted to quote? It’s about sort of living for the dream. You say this is a story about making a dream at all costs. How do you — what is it that allows you to sustain that dream? So many people give up pretty early in the game. What really matters?

OS: You know, I think tenacity is as much a part of success as anything. Anger certainly was there; it’s been steady. Anger at what we do in these situations and how we lie about it. It remains. It’s not the only focus of my life, of course. I have managed to balance my life out with happiness too. But certainly there’s a lot of residual anger there about what we’ve done and are still doing. What the hell are we doing with this budget, with our budget?

I mean our support of this military empire that we’ve created is beyond belief; beyond belief. After all the screwups we’ve seen, and we’ve seen it time and again from Vietnam to Iraq, one and two basically. And then of course Afghanistan and Syria; we had no business doing what we did. So it’s just a whole ideological warfare that we do, but there’s no point to it. It doesn’t do the world any good. It just creates bodies and destruction. We bring destruction and we call it peace.

DB: You have had some pretty strong critiques of your work. You’ve been successful, but a lot of people get very angry; for instance around JFK. Is it because the truth hurts?

OS: Oh, I guess it does. They don’t want to admit it. You’re asking me an obvious question. Why would they get angry? There’s a long list of people who’d like to see me, among others, see me dead.

DB: Right. And when you raised the issue about JFK; I mean you did the film, and I understand you’re still working on the story of JFK.

OS: The story never went away, because it was never solved. We just made — I made a documentary called JFK Revisited. It’s going to be released in November of this year in the United States. We showed it at Cannes very successfully; we sold 10-12 countries and it’s coming out here in November. So the case has never ended; they never solved it. The investigations kept coming.

Our film created a third investigation called The Assassination Records Review Board, and they interviewed a lot of people who were still alive back in ’94 and ’98. And they wrote up these things that were said and done, and a lot of people had provisionist stories to tell. And of course, it was ignored for the most part. It was really ignored by the media.

Americans love to say well, we’re going to make an investigation, another investigation. But then they never follow up because it’s tedious over four years to follow all the little details. Well we did. The people in this JFK research community did follow it, and there’s a lot there. There were — 60,000 documents were declassified, and almost two million pages.

On the other hand, Trump backed down at the last second and he was swamped with CIA objections; and he put a lid on it and he changed the law. He basically did it illegally; not with the authorization of Congress. And now the law is — they’re not respecting the law.

We still have these 20,000 documents that are still classified. And there’s a lot there. There may not be, but you have to get into the CIA people. The CIA has been most obstructive to the investigation. They don’t release the files on some of these key agents that appear around the edges of the story, like David Atlee Phillips, George Joannides in Miami, or William Harvey who was around the Cuba operation. There’s a lot there, but who knows what’s in there?

But the point is we accepted the Warren Commission, which was a joke. We go back in the film and show the basic evidence: the bullet, the rifle, the fingerprints, everything that matters in a murder trial. And we show it to be completely phony. There’s not one piece of evidence that really holds up against the so-called Oswald killer routine. It’s disgusting.

DB: What do you think? You’ve spent so much time; what are some of the basics that people should know, that should be taught in the history books; in the alternative history books?

OS: I’ve written about it, and the documentary is made. I don’t think in the time we have, Dennis — I’ve been on almost an hour and I do have other things I have to do today. I don’t think there’s time to go into it all. It’s about Oswald, it’s about the evidence, it’s about the Warrant Commission itself and how crooked it was. All this has come out in declassifications. We have to cover a lot of bases, and there’s no one headline.

Also, the big question is why, why, why was Kennedy killed? I keep re-emphasizing that. And I can tell you that our history books are still screwed up. I mean if you were to believe them, Mr. Johnson, Lyndon Johnson, succeeded Kennedy smoothly and continued his policies in Vietnam.

This is rubbish; complete rubbish. We have proof now through declassification that Kennedy was absolutely withdrawing from Vietnam, win or lose. And they said that’s what he told McNamara; McNamara said it in his book. He was Secretary of Defense. William — McGeorge Bundy, who was pro-Vietnam war, also says it very clearly in his book. These things are written years after.

People don’t pay attention. The historians still go on with that nonsense about Lyndon Johnson was a successor. But he changed everything in the foreign policy of Kennedy. Everything from Vietnam to Cuba to — Kennedy was working on another détente with the Soviet Union and Johnson never did anything towards détente. He moved the other direction, encouraged dictatorships and overthrew a government in Brazil, and all over the world, in Greece in 1967.

You see a complete repudiation of the Kennedy doctrine. Kennedy had the Alliance for Progress in South America; out the window with Johnson. In Africa, Kennedy was making huge strides to make allies with a whole new generation of Africans; all out the window. In Asia, of course, Kennedy was working with Indonesia; he liked Sukarno.

With Johnson, they get rid of Sukarno and there’s the bloodiest coup d’états of all time; a million people are killed because they were so-called Communists. But those are lists of course put together by the American CIA, and it’s just murder. That’s what it was, just outright murder. Anything the — stuff the Nazis did; just killing people and getting away with it. The world has gotten very violent and ugly, and we’ve played a huge role in bringing that about.

And of course, Dennis, you’re an hour in now. I do have to get out of here.

DB: All right, sure. All right. Well, I want to thank you for joining us. Can I just ask you, are there any more feature films coming up? Is there — are you in a different place now?

OS: Yeah, I’m in a different place. I’ve made a nuclear energy documentary, which is very, very fact-based and I think will be very interesting and possibly move some marbles around here. Because we need to get going and get clean energy.

We’ve got to get the CO2 out of the fucking system; out of the system. And it’s going to take a lot of work. People are dreaming when they think about if windmills and sun are going to do the whole job, they’re not. Certainly they’re good, but they need a lot of help. And we’re not going to make it unless we use nuclear energy, and a lot of it. A lot of it. So there has to be a change in thinking.

But it’s not just us; it’s the whole world that we have to change. The whole world.