It’s Time for the US To Bring Its Troops Home

Doug Bandow / AntiWar.com

(October 4, 2021) — President Joe Biden did what his three predecessors could or would not: halt a seemingly endless war. It took two decades, but American troops no longer are fighting in Afghanistan.

An important aspect of the US withdrawal was closing Washington’s bases, which once spread across the country. Uncle Sam left Bagram Air Base, America’s biggest facility in Afghanistan, on his way home.

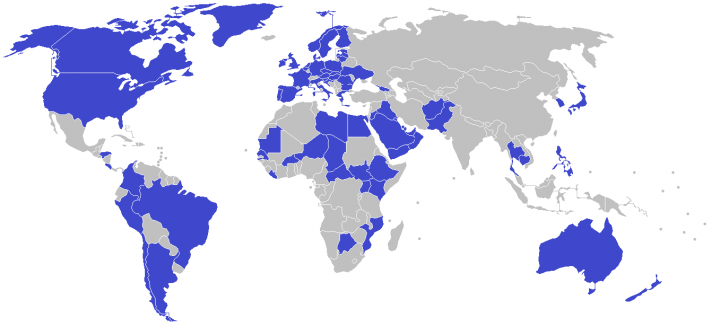

However, some 750 American military facilities remain open in 80 nations and territories around the world. No other country in human history has had such a dominant presence. Great Britain was the leading colonial power, but its army was small. London had to supplement its own troops with foreign mercenaries, as in the American Revolution. In wars with great powers Britain provided its allies with financial subsidies rather than soldiers.

Previous empires, such as Rome, Persia, and China, were powerful in their own realms but had little reach beyond. The latter never reached outside Asia. Persia was twice halted by the Greek city states. As great as Rome became, its writ never went much beyond the Mediterranean, with Central Europe, North Africa, and the Mideast its boundaries. The New World remained beyond the knowledge let alone control of all three.

A new Quincy Institute study by American University’s David Vine and World BEYOND War’s Patterson Deppen and Leah Bolger details the global US military presence. Washington has nearly three times as many bases as embassies and consulates. America also has three times as many installations as all other countries combined. The United Kingdom has 145. Russia two to three dozen. China five. Although the number of US facilities has fallen in half since the end of the Cold War, the number of nations hosting American bases has doubled. Washington is as willing to station forces in undemocratic as democratic countries.

The study figures the annual cost of this expansive base structure to be about $55 billion. Adding increased personnel expenses takes the total up to $80 billion. Wealthier countries, which needlessly enjoy what amounts to defense welfare, typically cover a portion of the cost through “host nation support.” Not so Washington’s newest clients. Indeed, through the Global War on Terror over the last two decades the US military spent as much as $100 billion on new construction, mostly in countries, like Iraq and Afghanistan, which were financial black holes.

Although American bases face intense local opposition in some areas, such as Okinawa, facilities are seen as welcome money-makers in others. When President Donald Trump proposed pulling US forces out of Germany many locals’ greatest concern was economic. Indeed, the whining of local politicians who saw America’s presence as a financial rather than security issue was loud enough to heard across “the Pond.” Not only did they believe that Americans owed them military protection. In their view Americans also had a duty to bolster their economies.

However, the price of Washington’s globe-spanning is more than economic. Explained Vine, et al.: “These bases are costly in a number of ways: financially, politically, socially, and environmentally. US bases in foreign lands often raise geopolitical tensions, support undemocratic regimes, and serve as a recruiting tool for militant groups opposed to the US presence and the governments its presence bolsters. In other cases, foreign bases are being used and have made it easier for the United States to launch and execute disastrous wars, including those in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, and Libya.”

Perhaps the most expensive installations were those established in Saudi Arabia after the first Gulf War. By renting out members of the US military as bodyguards for the Saudi royals Washington underwrote one of the most vile dictatorships in existence, a veritable totalitarian state with no political, religious, or social liberty. Although Crown Prince Mohammed “Slice & Dice” bin Salman, responsible for the murder and dismemberment of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi three years ago, has loosened some social strictures, he has greatly tightened political controls.

Worse from a foreign policy standpoint, America’s presence is one of the grievances which motivated Osama bin Laden to target the US Then Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz admitted in February 2003, before the invasion of Iraq, that America’s regional presence had cost “far more than money.” US bombing of Iraq and US troops in Saudi Arabia had “been Osama bin Laden’s principal recruiting device.” After the planned invasion, he added: “I can’t imagine anyone here wanting to … be there for another 12 years to continue helping recruit terrorists.”

Perhaps the most serious price of endless bases has been endless wars. Obviously, causation is complex. However, going to war usually leads to creation of new facilities. Such installations encourage a continuing military presence. Existence of nearby bases reduces the marginal cost of intervening and increases the maximal temptation to make new commitments, meddle in local controversies, and enter nearby conflicts. Observed the Quincy study: “Since 1980, US bases in the greater Middle East have been used at least 25 times to launch wars or other combat actions in at least 15 countries in that region alone. Since 2001, the US military has been involved in combat in at least 25 countries worldwide.”

American military facilities also raise expectations of host and neighboring nations. After Iran attacked Saudi oil facilities in September 2019 the well-pampered Saudi royals expected US retaliation but were sorely disappointed. Although President Donald Trump was right to allow the Saudis to “fight their own wars,” as he had tweeted five years before, America’s military presence, which Trump had increased, encouraged Riyadh to expect more – and might have motivated a more conventional president to act.

Vine, et al. point to other costs as well. The Department of Defense is a terrible environmental actor. Although its practices have much improved in recent years, the accumulated damage is enormous. There also are questions about Washington’s tendency to load up US territories, such as Guam, with military installations. Such areas are not exactly foreign, but the Quincy report contended that the heavy base presence “helped perpetuate their colonial relationship with the rest of the United States and their peoples’ second class US citizenship.”

Alas, DOD is less than forthcoming about the number of bases it maintains overseas. According to the report: “Until Fiscal Year 2018, the Pentagon produced and published an annual report in accordance with US law. Even when it produced this report, the Pentagon provided incomplete or inaccurate data, failing to document dozens of well-known installations. For example, the Pentagon has long claimed it has only one base in Africa – in Djibouti. But research shows that there are now around 40 installations of varying sizes on the continent; one military official acknowledged 46 installations in 2017.”

The Biden administration should make rationalizing the US base network a priority. Indeed, this should be an integral part of the Global Posture Review that the president announced in his February speech to State Department employees. He explained that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin would lead the process “so that our military footprint is appropriately aligned with our foreign policy and national security priorities. It will be coordinated across all elements of our national security.”

The initial task should be publicly listing military installations and their purposes. Then facilities should be consolidated, even if doing so angers local politicians and communities. After all, this process should be relatively painless overseas, in contrast to domestic base closures, which inevitably trigger fevered local and congressional opposition.

The next step would be tougher but necessary. The administration should rethink the underlying commitments used to justify the bases. Europe has no need of a US military presence for defense: the continent enjoys an 11-1 economic advantage and more than 3-1 population edge over Russia. South Korea has a 55-1 economic and 2-1 population superiority over the North. The Mideast Gulf monarchies are well-armed and now working with Israel as well as each other.

Washington’s presence in Iraq is unnecessary, since it and its neighbors could together confront any remaining threats from the Islamic State. America’s intervention in the Syrian civil war never made sense. The Marine Expeditionary Force stationed on Okinawa is tied to Korean rather than Chinese contingencies and America’s bases there unfairly burden the local population.

Ending US security guarantees and avoiding fights not America’s own would allow Washington to shutter many existing military facilities. Halting endless wars in the Mideast would diminish the importance of logistical nodes in Germany and elsewhere. In appropriate cases the US could replace its bases with emergency access to foreign facilities to deal with unexpected contingencies. In broad sweep Washington should move from frontline to reserve status around the world.

The international threat environment has changed dramatically since the end of World War II, yet America’s global network persists. The impact of the Soviet collapse and Warsaw Pact dissolution was too great not to have eliminated some US facilities, but otherwise the Pentagon has been reluctant to leave existing bases.

The only sure way to close a local installation, it seems, is to lose a war, as in Vietnam and Afghanistan. That needs to change. America no longer can afford to garrison the globe. The Biden administration should make the US into a normal country again. And that means no more imperial legions stationed around the world for purposes other than America’s defense.

Doug Bandow is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. A former Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.