War Powers Reform and the Pretense Thereof

David Swanson / World BEYOND War

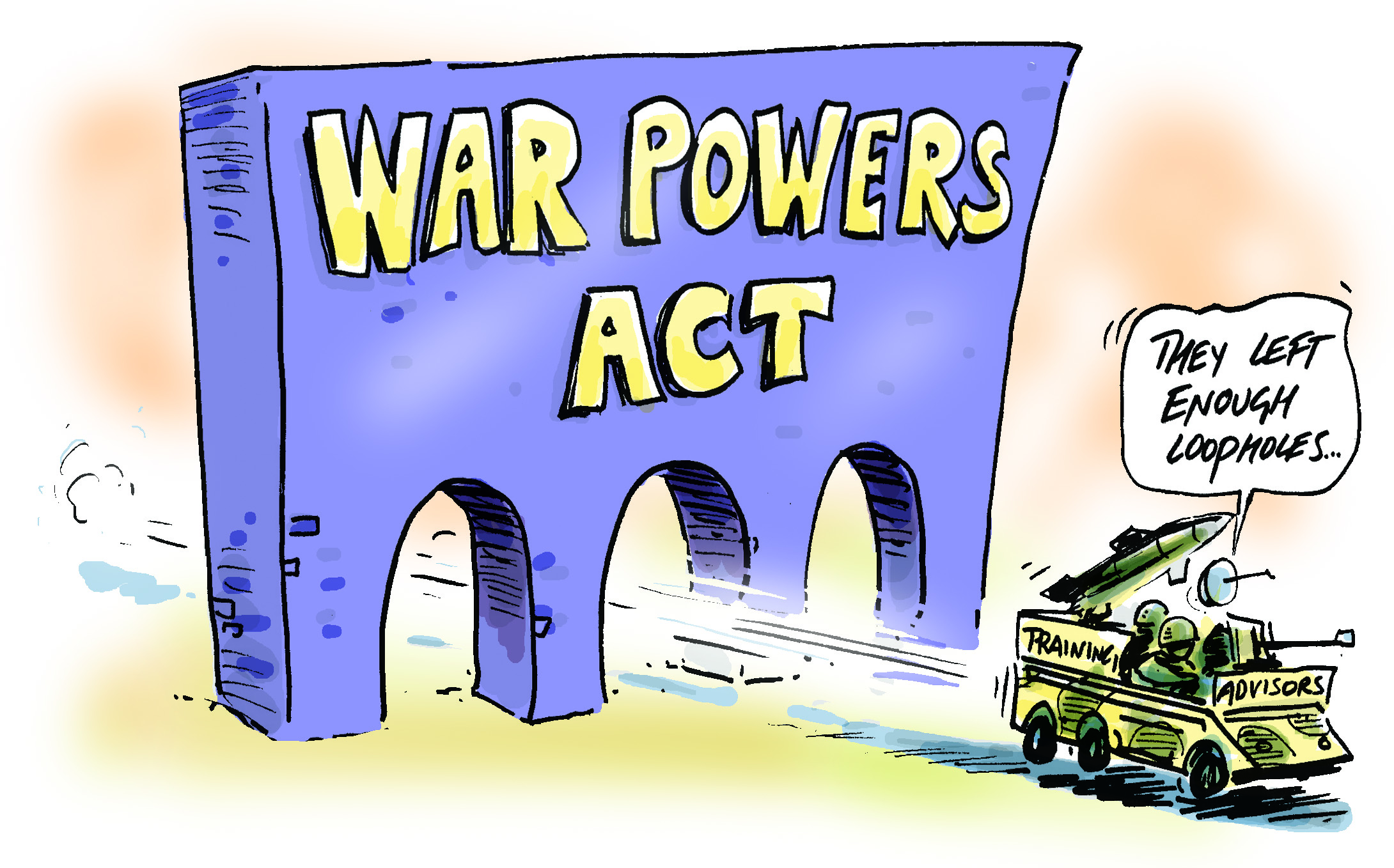

(October 13, 2021) — I’ve just read through three of the most boring but potentially most important documents around. One is the War Powers Resolution of 1973 which you can print on 6 pages and is what’s referred to as existing law even though it’s violated as routinely as air is breathed. Another is a war powers reform bill that has been introduced in the Senate and seems very likely to go nowhere (it’s 47 pages), and the third is a war powers reform bill in the House (73 pages) that seems virtually certain to go nowhere.

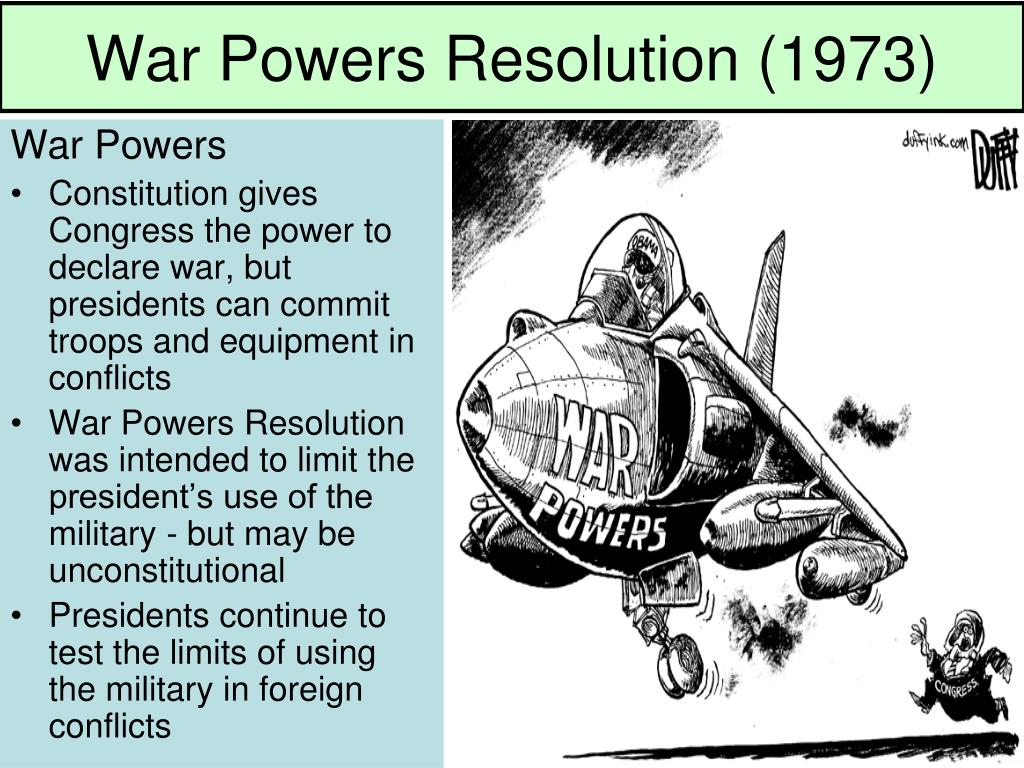

We have to set aside a couple of major concerns, beyond the unlikelihood of Congressional “leadership” allowing such bills to pass, before taking these things seriously.

First, we have to ignore / mindlessly violate the Hague Convention of 1907, the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 (short and clear enough to write on your palm or memorize), the United Nations Charter of 1945, the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949, and as regards much of the world the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. That is, we have to pretend that deciding who should commit war is a more legal and acceptable project than deciding who should commit any other crime.

Second, we have to prioritize improving the existing law over getting somebody to actually use it. The War Powers Resolution has been available to be used since 1973. It’s been used in the sense that individual House members have been able, under it, to force debates and (failed) votes on ending wars. This may have in various instances contributed to the eventual ending of wars by the entity that most members of Congress want to possess all war powers, namely the White House.

The closest Congress has come to ending a war through the War Powers Resolution was when it repeatedly voted in both houses to end U.S. participation in the War on Yemen — for which it could count on a veto from then-President Donald Trump. Once Joe Biden became president, Congress dropped that effort.

A Congress that won’t use the existing law could only be expected to use a new law to the extent that the new law forced it to. A Congress that in recent decades has re-criminalized torture more times than I can count has, on numerous topics, made clear its strong preference for creating new laws, even redundant laws, rather than actually using existing ones.

WHAT THE SENATE AND HOUSE BILLS HAVE IN COMMON

Setting those concerns aside, the Senate and House bills to alter the War Powers Resolution have some definite upsides and downsides. The Senate bill would repeal the entirety of the existing law and replace it with a different and longer one. The House bill would edit and rearrange the existing War Powers Resolution, instead of replacing it, but replace the majority of it, and add a great deal to it. The two bills seem to have the following things in common:

DOWNSIDE

They would eliminate the ability of a member or group of members of one house to force a debate and vote. None of the debates and votes that House members have compelled in the past would have been possible under this law without a Senator introducing the same resolution.

UPSIDES

Both bills would define the trick word “hostilities” in the current law to include “force deployed remotely” so that White House lawyers would have to stop claiming that bombing countries wasn’t war or hostilities so long as U.S. troops weren’t on the ground there. If this were law right now, the war on Afghanistan would no longer be “ended.”

Both bills would shorten the time for ending unauthorized wars from 60 to 20 days.

They would automatically (meaning this would work even with a feckless Congress of the sort we’ve had for over 200 years) cut off funding for unauthorized wars. Because this would happen without Congress doing anything, it could — in theory — be the most important change in these bills. But if Congress wouldn’t impeach or even (its preferred approach) sue a president in court, it might not matter to declare unauthorized the funding for wars that are unauthorized.

The bills would create requirements for any future authorizations of wars, such as a clearly defined mission, the identity of the groups or countries being attacked, etc.

They would also strengthen seldom used powers to control weapons sales to brutal foreign governments and to end and limit presidential declarations of emergencies.

SENATE BILL

ADDITIONAL DOWNSIDE

Unlike the House bill, the Senate bill would give presidents the unconstitutional power to commit the crime of using the U.S. military in partnership with another nation’s as long as this didn’t make the United States a party (a term it does not define) to the war. This would take the one war that Congress almost sort-of acted on under the War Powers Resolution (Yemen), and eliminate the ability to act on it.

ADDITIONAL UPSIDE

Unlike the House bill, the Senate bill would repeal all the existing AUMFs.

HOUSE BILL

ADDITIONAL DOWNSIDE

Unlike the Senate bill, the House bill would further erode the idea that impeachment is the appropriate remedy for serious offenses by holders of high office by writing into the law the right of Congress to sue in court a violator of a Congressional ban on a particular war.

ADDITIONAL UPSIDES

Unlike the Senate bill, the House bill would ban wars with a “serious risk” of violations of “the Law of Armed Conflict, international humanitarian law, or the treaty obligations of the United States,” which would seem to be a standard that would have prevented every U.S. war for the past century if actually taken seriously.

While both bills contain sections on weapons dealing, the House bill is more serious than the Senate. The House bill bans the transfer of weapons and training (“defense articles and defense services”) to countries that “commit genocide or violations of international humanitarian law.” This item would do so much good for the world and cost certain people so much money that it practically guarantees the bill will never be voted on.

While both bills contain sections on declarations of emergency, the House bill bans permanent emergencies, and ends existing “emergencies.”

CONCLUSION

I don’t like the downsides in these bills at all. I think they’re horrific, disgraceful, and absolutely indefensible. But I think they’re outweighed by the upsides, even in the Senate bill, though the House one is better. Yet, clearly best of all would be for Congress to make use of any of these things, either one of the new bills or the law as it exists today.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.