King George III Was

More Democratic Than the American Revolutionaries

David Swanson/ World BEYOND War

(October 22, 2021) — According to the Smithsonian Magazine — brought to you by the folks with museums up and down the National Mall in Washington D.C. — King George III was the democrat and humanitarian in 1776.

I’d hate for this to really feel like a bite in the ass, coming right on the heels of the dying of Colin Powell, who did so much for the idea that a war can be based on solid facts. It’s fortunate, perhaps, that World War II has largely replaced the American Revolution as an origin myth in US nationalism (as long as most of the basic facts about WWII are scrupulously avoided).

Still, there’s a childhood romanticism, a glorious fairy tale that’s rather viciously eaten away at every time we discover that George Washington didn’t have wooden teeth or always tell the truth, or that Paul Revere didn’t ride alone, or that slave-owning Patrick Henry’s speech about liberty was written decades after he died, or that Molly Pitcher didn’t exist. It’s enough to make me almost want to either cry or grow up.

And now here comes the Smithsonian Magazine to rob us even of the perfect enemy, the white guy in the Hamilton musical, the lunatic in Hollywood movies, His Royal Highness of the blue piss, the accused and convicted in the Declaration of Independence. If it weren’t for Hitler, I honestly don’t know what we would have left to live for.

Actually, what the Smithsonian has printed, with apparently no review whatsoever by the Intelligence Community, is adapted from a book called The Last King of America by future Espionage Act defendant Andrew Roberts. Daniel Hale is in solitary confinement for the next four years merely for telling us what the US government does with drones and missiles. Compare that to this from Mr. Roberts, quoting King George on the evils of slavery:

“‘The pretexts used by the Spaniards for enslaving the New World were extremely curious,’ George notes; ‘the propagation of the Christian religion was the first reason, the next was the [Indigenous] Americans differing from them in colour, manners, and customs, all of which are too absurd to take the trouble of refuting.’

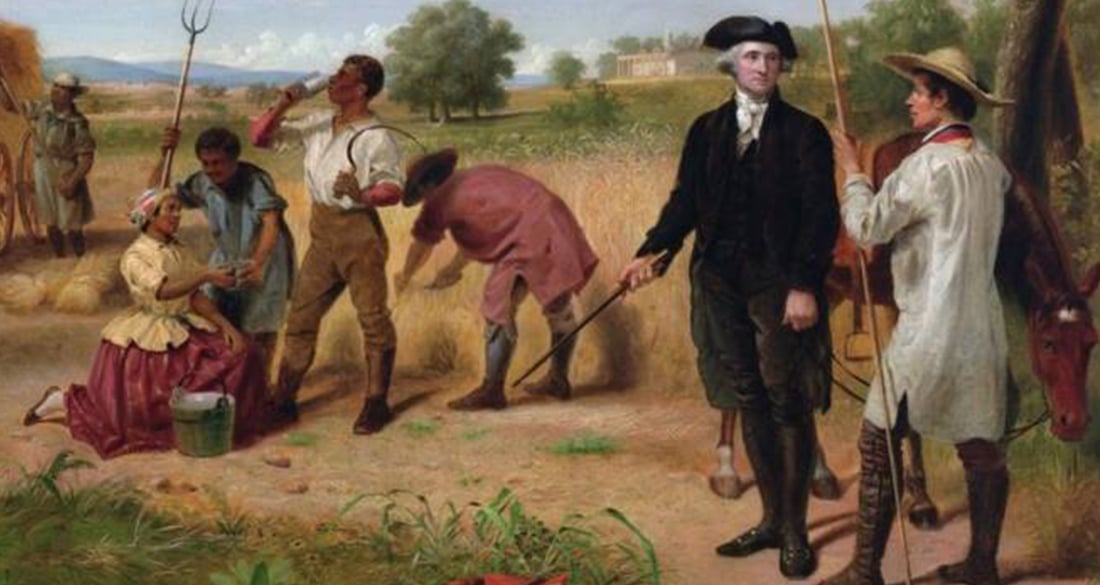

As for the European practice of enslaving Africans, he wrote, ‘the very reasons urged for it will be perhaps sufficient to make us hold such practice in execration.’ George never owned slaves himself, and he gave his assent to the legislation that abolished the slave trade in England in 1807. By contrast, no fewer than 41 of the 56 signatories to the Declaration of Independence were slave owners.”

So, the fact that King George didn’t own slaves while Thomas Jefferson couldn’t get enough of them is hardly relevant to the indictment against the king set forth in the Declaration of Independence, which Andrew Roberts (if that’s his real name) describes as generating myth.

Now that’s just not fair. The American Revolutionaries talked about “slavery” and “freedom” but those were never meant to be compared with actual, you know, slavery and freedom. They were rhetorical devices meant to indicate the rule of England over its colonies and the ending thereof. In fact, many of the American Revolutionaries were motivated at least in part by the desire to protect slavery from abolition under English rule.

“It was the Declaration that established the myth that George III was a tyrant. Yet George was the epitome of a constitutional monarch, deeply conscientious about the limits of his power. He never vetoed a single Act of Parliament, nor did he have any hopes or plans to establish anything approaching tyranny over his American colonies, which were among the freest societies in the world at the time of the Revolution: Newspapers were uncensored, there were rarely troops in the streets and the subjects of the 13 colonies enjoyed greater rights and liberties under the law than any comparable European country of the day.”

I admit that doesn’t sound good. Still, some of the charges in the Declaration must have been true, even if many of them basically amounted to “he’s in charge and shouldn’t be,” but the ultimate climactic charge in the document was this:

“He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

It’s odd that the freedom lovers should have had people domestically among them who could threaten insurrections. I wonder who those people could have been. And where did the merciless savages come from — who invited them into an English country in the first place?

The American revolutionaries, through their revolution for freedom, opened up the West to expansion and wars against the Native Americans, and in fact waged genocidal war on the Native Americans during the American Revolution, followed swiftly by wars launched into Florida and Canada.

Revolutionary hero George Rogers Clark said that he would have liked to “see the whole race of Indians extirpated” and that he would “never spare Man woman or child of them on whom he could lay his hands.” Clark wrote a statement to the various Indian nations in which he threatened “Your Women & Children given to the Dogs to eat.” He followed through on his words.

So, perhaps the Revolutionaries had flaws, and perhaps in some contexts King George was a decent guy for his time, but he was still a bitter nasty enemy toward the freedom loving patriots, er, I mean terrorists, or whatever they were, right? Well, according to Roberts:

“George III’s generosity of spirit came as a surprise to me as I researched in the Royal Archives, which are housed in the Round Tower at Windsor Castle. Even after George Washington defeated George’s armies in the War of Independence, the king referred to Washington in March 1797 as ‘the greatest character of the age,’ and when George met John Adams in London in June 1785, he told him, ‘I will be very frank with you. I was the last to consent to the separation [between England and the colonies]; but the separation having been made, and having become inevitable, I have always said, and I say now, that I would be the first to meet the friendship of the United States as an independent power.’ (The encounter was very different from the one depicted in the miniseries ‘John Adams,’ in which Adams, played by Paul Giamatti, is treated dismissively.)”

As these voluminous papers make clear, neither the American Revolution nor Britain’s defeat can be blamed on George, who acted throughout as a restrained constitutional monarch, closely following the advice of his ministers and generals.”

But then, what was really the point of the bloody murderous war? Many nations — including Canada as the nearest example — have gained their independence without wars. In the United States, people claim that the “founding fathers” fought a war for independence, but if we could have had all the same advantages without the war, would that not have been better than killing tens of thousands of people?

Back in 1986, a book was published by the great nonviolent strategist Gene Sharp and later Virginia State Delegate David Toscano, and others, called Resistance, Politics, and the American Struggle for Independence, 1765-1775.

Those dates are not a typo. During those years, the people of the British colonies that would become the United States used boycotts, rallies, marches, theatrics, noncompliance, bans on imports and exports, parallel extra-legal governments, the lobbying of Parliament, the physical shutting down of courts and offices and ports, the destruction of tax stamps, endless educating and organizing, and the dumping of tea into a harbor — all to successfully achieve a large measure of independence, among other things, prior to the War for Independence.

Home-spinning clothes to resist the British Empire was practiced in the future United States long before Gandhi tried it. They don’t tell you that in school, do they?

The colonists didn’t talk about their activities in Gandhian terms. They didn’t foreswear violence. They sometimes threatened it and occasionally used it. They also, disturbingly, talked of resisting “slavery” to England even while maintaining actual slavery in the “New World.” And they spoke of their loyalty to the King even while denouncing his laws.

Yet they largely rejected violence as counter-productive. They repealed the Stamp Act after effectively nullifying it. They repealed nearly all of the Townsend Acts. The committees they organized to enforce boycotts of British goods also enforced public safety and developed a new national unity.

Prior to the battles of Lexington and Concord, the farmers of Western Massachusetts had nonviolently taken over all the courthouses and booted the British out. And then the Bostonians turned decisively to violence, a choice that need not be excused, much less glorified, but one that certainly required a demonized individual enemy.

While we imagine that the Iraq War has been the only war started with lies, we forget that the Boston Massacre was distorted beyond recognition, including in an engraving by Paul Revere that depicted the British as butchers. We erase the fact that Benjamin Franklin produced a fake issue of the Boston Independent in which the British boasted of scalp hunting. And we forget the elite nature of the opposition to Britain. We drop down the memory hole the reality of those early days for ordinary nameless people. Howard Zinn explained:

“Around 1776, certain important people in the English colonies made a discovery that would prove enormously useful for the next two hundred years. They found that by creating a nation, a symbol, a legal unity called the United States, they could take over land, profits, and political power from favorites of the British Empire. In the process, they could hold back a number of potential rebellions and create a consensus of popular support for the rule of a new, privileged leadership.”

In fact, prior to the violent revolution, there had been 18 uprisings against colonial governments, six black rebellions, and 40 riots. The political elites saw a possibility for redirecting anger toward England. The poor who would not profit from the war or reap its political rewards had to be compelled by force to fight in it. Many, including enslaved people, promised greater liberty by the British, deserted or switched sides.

Punishment for infractions in the Continental Army was 100 lashes. When George Washington, the richest man in America, was unable to convince Congress to raise the legal limit to 500 lashes, he considered using hard labor as a punishment instead, but dropped that idea because the hard labor would have been indistinguishable from regular service in the Continental Army. Soldiers also deserted because they needed food, clothing, shelter, medicine, and money.

They signed up for pay, were not paid, and endangered their families’ wellbeing by remaining in the Army unpaid. About two-thirds of them were ambivalent to or against the cause for which they were fighting and suffering. Popular rebellions, like Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts, would follow the revolutionary victory.

So, maybe the violent Revolution wasn’t needed, but the belief that it was helps us to appreciate the current corrupt oligarchy we’re living in as something to mislabel “democracy” and start an apocalyptic war on China over. So, you can’t say anybody died in vain.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.