Honduras Is Getting Rid of an Oppressive Regime

That Washington Could No Longer Support

Stephen Kinzer / The Boston Globe

(December 22, 2021) — “Beyond unbelievable!” Those were the first words of an email I received after last month’s election in Honduras, from a scholar who has spent years studying that ravaged country. The result was indeed amazing. Honduras has just stunned Latin America and the world.

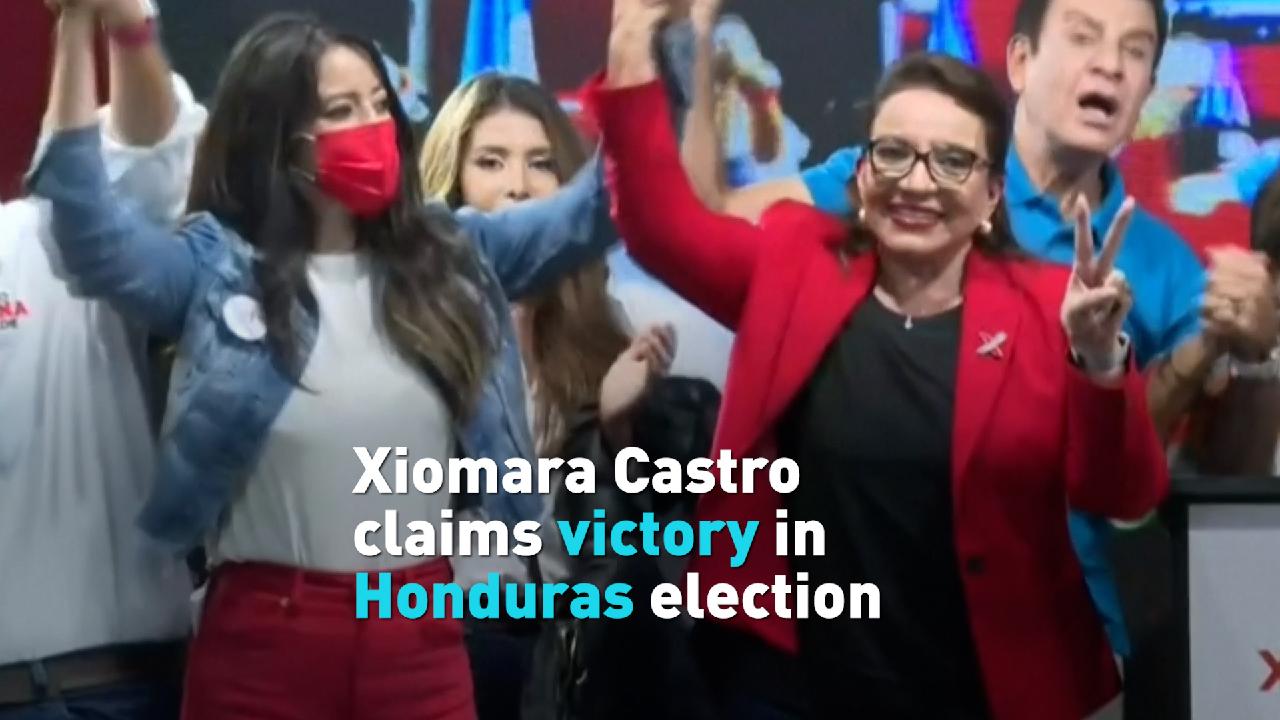

A venal clique has ruled Honduras for the last 12 years. Violence became horrific, driving thousands to flee the country in migrant caravans. Now an impassioned eco-feminist and anti-corruption campaigner, Xiomara Castro, is poised to assume the presidency. “Get out war, get out hate!” she cried to a delirious throng after her decisive victory at the polls. “Get out death squads! Get out corruption! Get out drug trafficking and organized crime! No more poverty and misery in Honduras!”

Castro’s victory could be a turning point for Honduras, but it also has wider significance. It marks a rare retreat by the United States in Central America. US officials, led by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, cheered when the elected president of Honduras was overthrown in a coup in 2009. We considered him too leftist and eagerly embraced a new regime allied with US political and economic interests. That regime, however, became so corrupt and repressive that it set off mass migration toward the United States. The prospect of more migration terrifies the Biden administration, because it is an intensifying issue in US politics.

Four years ago, Washington looked the other way as the Honduran elite appeared to steal an election to keep itself in power. This time we changed course. The regime we have supported for more than a decade was pushing people to flee toward the Rio Grande. Biden calculated that a fiery female president with a social conscience might persuade them to stay home. This may be the new US standard for governments in Central America: We’ll support anythat reduce migration.

Shortly before the Nov. 28 election, Assistant Secretary of State Brian Nichols traveled to Honduras. According to Dana Frank, author of “The Long Honduran Night: Resistance, Terror and the United States in the Aftermath of the Coup,” his message to the governing group was simple. Castro held a big lead in opinion polls, and the United States had decided she must be allowed to win and take office. Attacks on Castro’s supporters ended, she won a decisive victory, and her opponent conceded graciously.

Condemned by geography, Honduras has been a vassal of the United States for more than a century. We first overthrew a Honduran president in 1911, worked with fruit companies to corrupt governments over several generations, and in the 1980s militarized the country so it could serve as a base for our war against neighboring Nicaragua. We backed the 2009 coup because we believed the elected president, Manuel Zelaya, was becoming too friendly with leftists in the hemisphere. Now, 12 years later, we are effectively admitting our mistake and allowing the old regime to come back to power. President-elect Castro is Zelaya’s wife, so the return of the pre-coup regime is familial as well as political.

Castro calls herself a democratic socialist. She supports the Cuban and Venezuelan governments we detest. Her victorious coalition is the kind that normally makes Washington worry: radicalized feminist and environmental groups, gays, Indigenous people, Afro-Hondurans, and anti-corporate campaigners of various stripes. She plans to cut diplomatic relations with Taiwan and recognize Beijing. In her sweeping political platform, she pledges to release political prisoners, cancel taxes that fall mainly on the poor, “work to eradicate patriarchy and femicide,” and produce a new constitution free from “laws of the dictatorship.” She wants to change the country’s economic model, which is based on promoting big business and foreign investment and has been shaped by the US-dominated World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

Among her first targets will be corporations that dam Honduran rivers, cut forests, and dig for minerals. “I will order immediate cancellation of monopolies,” she vowed. “I will not give any further permission for exploitation of river basins or for open-pit mines, and will do everything legally possible to cancel existing permits that have led to the destruction of our natural environment.”

Never in the last century would the United States have accepted such a president in Central America. How the worm turns — and it’s all because of migration! Biden has evidently decided that any Central American leader who can curb migration is good for us, even if she likes Cuba and hates the IMF. His political prospects now depend in part on the success of democracy in Central America — ironic in a region where the United States is known more for crushing democracy than encouraging it.

Castro takes over a country that has been devastated economically, politically, socially, and morally. Prosecutors in New York are preparing to indict the outgoing president for drug trafficking when he leaves office next month. The Honduran state has failed to respond to urgent challenges ranging from the COVID-19 pandemic to climate change. Gang violence terrifies peaceable citizens. Business tycoons and drug lords control murderous police forces.

Yet despite these daunting challenges, democracy in Honduras no longer faces its longtime barrier: resistance from Washington. That makes results of the recent election “beyond unbelievable.” This is a remarkable historical moment. For the first time ever, the United States seems to be hoping that a socialist government in Latin America will succeed.

Stephen Kinzer is a senior fellow at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.