Are Americans Finally Tiring of War?

Gil Barndollar / Newsweek

(January 27, 2022) — The Soviet Union voted itself out of existence on Dec. 26, 1991, in perhaps the greatest peaceful triumph of liberty in world history. But in the three decades since, bellicosity in the name of liberty has most distinguished the victorious United States to many observers around the globe. Despite historically unprecedented power and security — a brief unipolar moment as the world’s first “hyperpower” — America couldn’t help itself, frequently trying to provide global leadership at the point of a bayonet.

Bloodless triumph at the Berlin Wall was followed swiftly by the Highway of Death in Kuwait. The United States may have been both morally and strategically correct in ejecting Iraqi forces from Kuwait, but the crushing victory presaged more wars to come. President George H. W. Bush was jubilant, exulting to a group of lobbyists, “by God, we’ve kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all.”

Armed interventions in Somalia, Haiti and the Balkans helped fill the ’90s. In the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks, the United States invaded Afghanistan and then Iraq, with the overwhelming support of the American people and their elected representatives. There was heady talk of driving on to Tehran and transforming the Middle East. Anti-war voices suffered “cancellation” long before the term was coined. A septuagenarian Donald Rumsfeld was briefly a sex symbol in some quarters.

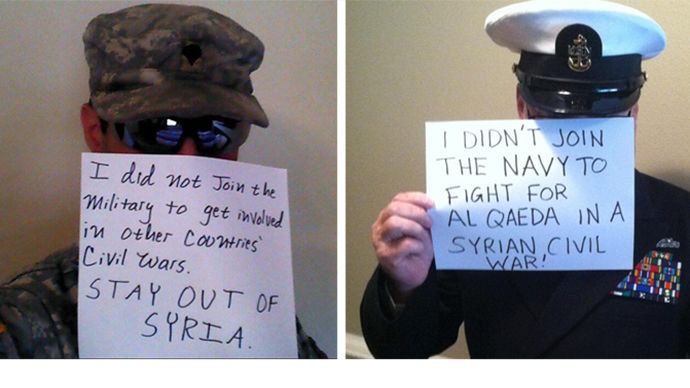

Two decades and two lost wars later, has America’s enthusiasm for war finally waned?

Fatigue with what was once dubbed the “Global War on Terror” is of course nothing new. Americans rightly soured on the Iraq war 15 years ago, when the scale of that disaster became undeniable to all but the most enthusiastic of hawks. Tolerance for the initially more justifiable intervention in Afghanistan lasted longer, but by the time President Joe Biden pulled the plug last April, a healthy majority of Americans were ready for their country’s role in Afghanistan to end.

What has changed is an unwillingness to blithely accept new military interventions despite the predictable think tank and media chorus explaining their necessity. When Iranian missiles and drones struck Saudi oil processing facilities in September 2019, briefly cutting Saudi Arabia’s oil production in half, Americans rejected the ossified Carter Doctrine, regardless of whether they could identify it as such. A poll found that just 13 percent of Americans supported going to war on Saudi Arabia’s behalf.

With Russia and Ukraine now potentially on the verge of major war, again most Americans have little appetite for shedding blood on behalf of a putative partner. A recent poll by YouGov, commissioned by the Charles Koch Institute, found that only 27 percent of Americans think the United States should go to war in the event of a Russian invasion of Ukraine. Four times as many respondents wanted less rather than more US militaryengagement around the world.

Politicians have gotten the message. Though President Donald Trump‘s failed “maximum pressure” campaign helped drive the United States and Iran to the brink, he balked repeatedly when faced with the prospect of open war with the Islamic Republic.

A Bradley Fighting Vehicle during a joint military exercise in Syria,

President Biden, whether leading or being led by public opinion, has also gotten the message. On Dec. 8, he unequivocally ruled out sending US troops to Ukraine, telling reporters, “That is not on the table.”

Defenders of American interventionism will generally excuse most US wars as the price of primacy. Flinging cruise missiles is a sad necessity, lest a dangerous vacuum develop anywhere in the world. Even Trump, detested by most of the commentariat, received hosannas when he authorized military strikes far from America’s shores. After a performative cruise missile salvo on Syria in 2017, CNN‘s Fareed Zakaria solemnly told his viewers, “I think Donald Trump became president of the United States last night.”

But it appears that when it comes to wars of choice, most Americans are finally tuning out the stars of the Fourth Estate. Twenty years of what have rightly been dubbed “endless wars” have soured citizens of all political persuasions on the idea that American arms and soldiers are the solution for what ails other countries. Supermajorities of both Democrats and Republicans think America’s focus should be on its domestic problems, however they might be defined.

A recent cover of The Economist asked plaintively, “What would America fight for?” A pair of star-spangled gloves hung below the question. After 30 years of militarized global primacy, America is finally asking itself whether it was worth it. We appear to have passed the high-water mark of what professor Andrew Bacevich rightly dubbed “the new American militarism.”

Hawks now fear war from weakness, with every provocation a Munich moment. Skeptics, their numbers growing in both of America’s political tribes, increasingly reject both threat inflation and military solutions to problems far from America’s shores.

Have Americans turned a corner and begun an unconscious but inexorable return to their country’s traditional suspicion of foreign entanglements? It is too soon to tell. But this belated, inchoate reluctance to continue to drop the gloves at the drop of a hat is real. The rest of the world should plan accordingly.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.