After Undermining ICC,

US Now Wants It to Charge Russians

(April 17, 2022) — Although the United States has tried mightily to undermine the International Criminal Court (ICC) since it became operational in 2002, the U.S. government is now pushing for the ICC to prosecute Russian leaders for war crimes in Ukraine. Apparently, Washington thinks the ICC is reliable enough to try Russians but not to bring U.S. or Israeli officials to justice.

On March 15, the Senate unanimously passed S. Res 546, which “encourages member states to petition the ICC or other appropriate international tribunal to take any appropriate steps to investigate war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the Russian Armed Forces.”

When he introduced the resolution, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-South Carolina) said, “This is a proper exercise of jurisdiction. This is what the court was created for.” The United States has refused to join the ICC and consistently tries to undercut the court. Yet a unanimous U.S. Senate voted to utilize the ICC in the Ukraine conflict.

Since February 24, when the Russian Federation launched an armed attack against Ukraine, horrific images of destruction have been ubiquitous. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has documented 3,455 civilian casualties, including 1,417 killed and 2,038 injured as of April 3. Most of those casualties have been caused by explosive weapons with a wide impact area, which includes heavy artillery and multiple launch systems as well as air and missile strikes.

On February 28, Karim Khan, chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, opened an investigation into the situation in Ukraine. He said that his preliminary examination found a reasonable basis to believe that alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity had been committed in Ukraine. Khan’s formal investigation will “also encompass any new alleged crimes . . . that are committed by any party to the conflict on any part of the territory of Ukraine.”

As I explained in prior Truthout columns, in spite of U.S.-led NATO’s provocation of Russia over the past several years, the Russian invasion of Ukraine constitutes illegal aggression.

Nevertheless, the ICC does not have jurisdiction to prosecute Russian leaders for the crime of aggression.

The ICC’s Rome Statute Prohibits Aggression

In 1946, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg called the waging of aggressive war “essentially an evil thing,” adding that, “to initiate a war of aggression . . . is not only an international crime; it is the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.”

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Tribunal, called aggressive war “the greatest menace of our times.” Jackson said, “If certain acts in violation of treaties are crimes, they are crimes whether the United States does them or whether Germany does them, and we are not prepared to lay down a rule of criminal conduct against others which we would not be willing to have invoked against us.”

Aggression is prohibited by the ICC’s Rome Statute. Article 8bis defines the crime of aggression as “the planning, preparation, initiation or execution, by a person in a position effectively to exercise control over or to direct the political or military action of a State, of an act of aggression which, by its character, gravity and scale, constitutes a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.”

Adopting the central prohibition of the UN Charter against the use of aggressive force, Article 8bis defines an act of aggression as “the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Charter of the United Nations.” The charter only allows the use of military force in self-defense or with the consent of the Security Council, neither of which happened before Russia invaded Ukraine.

In order to secure a conviction for aggression, the prosecutor of the ICC must prove that a leader who exercised control over the military or political apparatus of a country ordered an armed attack against another country. An armed attack can include bombing or attacking the armed forces of other country.

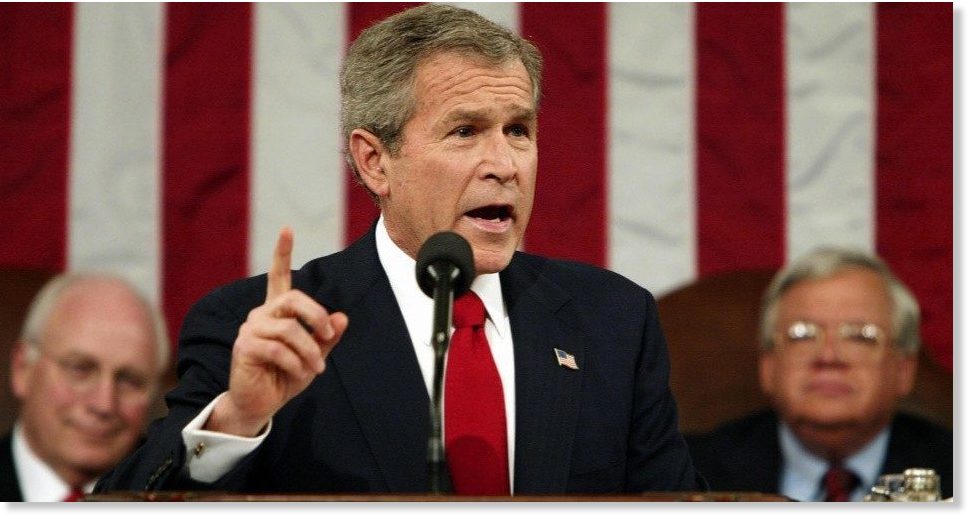

The attack must be a “manifest” violation of the UN Charter in its character, scale and gravity, which includes only the most serious forms of the illegal use of force. For example, a single gunshot would not qualify but George W. Bush’s illegal invasion of Iraq would.

But the ICC’s jurisdictional scheme for the crime of aggression is much more restrictive than its regime for punishing the other crimes under the Rome Statute — genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The original Rome Statute said that those three crimes could be prosecuted in the ICC if: (1) the defendant’s country was a party to the statute; (2) one or more elements of the crime was committed in the territory of a State Party; (3) the defendant’s country accepted ICC jurisdiction for the matter; or (4) upon referral by the UN Security Council. But the statute left the definition and jurisdictional scheme for prosecuting the crime of aggression to future negotiation.

In 2010, the final negotiations in Kampala, Uganda, added an amendment which is now Article 15bis(5) of the Rome Statute. It is this article that prevents the ICC from taking jurisdiction over Russian leaders for the crime of aggression.

Most countries at the Kampala Review Conference thought they had agreed that States Parties were covered by the jurisdictional scheme unless they “opted out” under Article 15bis(4). But in 2017, France, the U.K., and several other States reversed the presumption of Article 15bis(4).

Under their new interpretation, States Parties were presumed to be “out” of the jurisdictional scheme unless they “opted in” by ratifying the amendment. In other words, the ICC would not have jurisdiction to prosecute nationals of States Parties that had not ratified the amendment.

If the crime of aggression was covered by the same jurisdictional regime as war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity, the ICC could prosecute Russian officials for aggression. Although neither Russia nor Ukraine has ratified the Rome Statute, Ukraine accepted ICC jurisdiction under Article 12(3) of the statute. Russia would veto any Security Council referral of the matter to the ICC.

The prohibition on aggression is so basic that it is considered to be jus cogens, a preemptory norm of international law which can never be committed under any circumstances. There is no immunity defense or statute of limitations for a jus cogens norm.

The Security Council could convene a special tribunal to try the crime of aggression committed in Ukraine, but again, Russia would veto such a resolution.

Another option is for countries to prosecute Russian leaders for aggression in their domestic courts under the doctrine of universal jurisdiction. Some crimes are so heinous, they are considered to be crimes against the entire world.

US Calls for ICC Prosecution of Russians But Shuns Jurisdiction for US and Israeli Leaders

“Americans are rightfully horrified when they see civilians killed by Russian bombardment in Ukraine,” Medea Benjamin and Nicolas J.S. Davies wrote in the LA Progressive, “but they are generally not quite so horrified, and more likely to accept official justifications, when they hear that civilians are killed by U.S. forces or American weapons in Iraq, Syria, Yemen or Gaza.”

Benjamin and Davies attribute this to the complicity of the corporate media “by showing us corpses in Ukraine and the wails of their loved ones, but shielding us from equally disturbing images of people killed by U.S. or allied forces.”

The United States maintains a double standard when it comes to the ICC. The U.S. is not a party to the Rome Statute. Although former President Bill Clinton signed the statute as he left office, he urged incoming President George W. Bush to refrain from sending it to the Senate for advice and consent to ratification. Whereas signing indicates an intent to ratify, a country becomes a State Party once it ratifies the treaty.

Bush went one step further and in an unprecedented move, his administration unsigned the Rome Statute. Congress then passed the American Service-Members’ Protection Act (ASPA), which contains a clause called the “Hague Invasion Act.” It says that if a U.S. or allied national is detained by the ICC, the U.S. military can use armed force to extricate them.

But the Dodd Amendment, which is one provision of the ASPA, “specifically permits the United States to assist international efforts to bring to justice ‘foreign nationals’ who commit war crimes and crimes against humanity,” former Sen. Christopher Dodd and John Bellinger, former legal adviser for the National Security Council and State Department, wrote in The Washington Post.

Another provision says that the ASPA “would clearly allow the United States to share intelligence information about Russian offenses, to allow expert investigators and prosecutors to assist, and to provide law enforcement and diplomatic support to the Court,” Dodd and Bellinger added.

Although the U.S. is not a State Party to the Rome Statute, it participated in the negotiations on the crime of aggression. The United States has consistently tried to undermine the ICC. The Bush administration effectively blackmailed 100 countries that were States Parties by forcing them to sign bilateral immunity agreements in which they promised not to turn over U.S. persons to the ICC or the United States would withhold foreign aid from them.

In 2020, after the ICC launched an investigation into possible war crimes and crimes against humanity by U.S. as well as Taliban leaders in Afghanistan, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on ICC officials but Joe Biden reversed them.

When Khan became chief prosecutor of the ICC, he narrowed the scope of the investigation in Afghanistan by limiting suspects to Taliban and ISIS leaders. He cited “the limited resources available to my Office relative to the scale and nature of crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court that are being or have been committed in various parts of the world.”

Khan stated, “I have therefore decided to focus my Office’s investigations in Afghanistan on crimes allegedly committed by the Taliban and the Islamic State — Khorasan Province (“IS-K”) and to deprioritise other aspects of this investigation.”

“This was clearly a political decision — there’s really no other way it can be interpreted,” human rights lawyer Jennifer Gibson told Al Jazeera. Gibson’s human rights group Reprieve submitted representations for clients who alleged torture by the CIA in the brutal Bagram prison, as well as relatives of civilians allegedly killed in U.S. drone strikes in Afghanistan. “It gave the US and their allies a get out of jail free card,” Gibson said.

The Biden administration continues to oppose the pending ICC investigation into Israeli war crimes in Gaza. It has expressed “serious concerns about the ICC’s attempts to exercise its jurisdiction over Israeli personnel.”

Former ICC Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda.

Following a five-year preliminary examination, former ICC Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda found a reasonable basis to mount an investigation of “the situation in Palestine.” She was “satisfied that (i) war crimes have been or are being committed in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip . . . (ii) potential cases arising from the situation would be admissible; and (iii) there are no substantial reasons to believe that an investigation would not serve the interests of justice.”

Bensouda initiated the preliminary examination six months after Israel’s 2014 “Operation Protective Edge,” when Israeli military forces killed 2,200 Palestinians, nearly one-quarter of them children and more than 80 percent civilians.

“So, the U.S. wants to help the International Criminal Court prosecute Russian war crimes while barring any possibility the ICC could probe U.S. (or Israeli) war crimes,” observed Reed Brody, a commissioner for the International Commission of Jurists, an international human rights nongovernmental organization.

U.S. hypocrisy is no more apparent than in the first “Whereas” clause of the Senate’s unanimous resolution condemning Russia. It says, “Whereas the United States of America is a beacon for the values of freedom, democracy, and human rights across the globe . . .”

One hundred members of the U.S. Senate affirmed that sentiment in spite of the U.S. wars of aggression in Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan, and the commission of U.S war crimes. If the senators truly believe that the ICC is dependable enough to prosecute Russian leaders, they should push Biden to send the Rome Statute to them for advice and consent to ratification. What’s good for the Russian goose should also be good for the U.S. gander.

Marjorie Cohn is professor emerita at Thomas Jefferson School of Law, former president of the National Lawyers Guild, and a member of the national advisory board of Veterans For Peace and the bureau of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers. Her books include Drones and Targeted Killing: Legal, Moral and Geopolitical Issues. She is co-host of “Law and Disorder” radio.

Copyright © Truthout.org. Reprinted with permission.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.