Trudeau Orders an Immediate Freeze

on the Sale of Handguns in Canada

Giulia Heyward / National Public Radio

(October 22, 2022) — Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is placing a nationwide freeze on the sale, purchase and transfer of handguns, effective immediately.

The handgun freeze is the latest in an ongoing battle among Canadian lawmakers over gun control measures. In parliament, legislators are still debating the passage of a bill, introduced in May, that would be one of the strongest pieces of gun control legislation in decades. The new handgun freeze is an “immediate action” the Trudeau administration said it is taking as conversation around the bill continues.

“When people are being killed, when people are being hurt, responsible leadership requires us to act,” Trudeau said at a news conference on Friday, announcing the new measure. “Recently again, we have seen too many examples of horrific tragedies involving firearms.”

People can no longer buy, sell, or transfer

handguns within Canada — and they cannot bring

newly acquired handguns into the country.

— Justin Trudeau, October 21, 2022

In addition to a ban on handgun sales, it is also now forbidden to bring newly acquired handguns into Canada. The freeze is being met with elation from gun reform groups who welcomed the immediate action.

“Reducing the proliferation of handguns is one important example of the evidence-based measures Canada needs to reduce gun violence and save lives,” Canadian Doctors for Protection from Guns tweeted in response to the news.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-mco.s3.amazonaws.com/public/WIS5GUKGUNA5FF33DP2PXYZLHM.jpg)

Promoting Stability or Fueling Conflict? The Impact of

US Arms Sales on National and Global Security

William D. Hartung / Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft Paper No. 9

Executive Summary

(October 20, 2022) — Following Saudi Arabia’s recent decision to cut oil production, a move that will raise prices in the West and is widely seen as a slight to the United States, two Democratic lawmakers have called for a freeze in all arms sales and military support to the Kingdom.1

For years, US politicians and commentators have claimed that American support for Saudi Arabia — which includes providing 70 percent of its weapons and technical support that its air force relies on to conduct its bombing campaign against Yemen — is necessary to ensure the Kingdom will provide stable energy supplies and side with the United States in geopolitical disputes. But the latest Saudi move has given the lie to these claims. It provides yet another urgent prompt to rethink US arms transfer policies to Saudi Arabia and, in fact, around the world.

The administration needs to address a number of key issues if US policy on arms sales is to be made consistent with long-term US interests. The key policy consideration is how to restrict sales to those that will help allies defend themselves without provoking arms races or increasing the prospects for conflict. Of particular note, the Australia-UK-US, or AUKUS submarine deal will benefit US contractors but risks fueling arms competition and increasing tensions with China.

Aid designed to help Ukraine defend itself from Russia has proceeded at the most rapid pace of any US military assistance program since at least the peak of the Vietnam War. But the United States has failed to offer an accompanying diplomatic strategy aimed at ending the war before it evolves into a long, grinding conflict or escalates into a direct US-Russian confrontation.

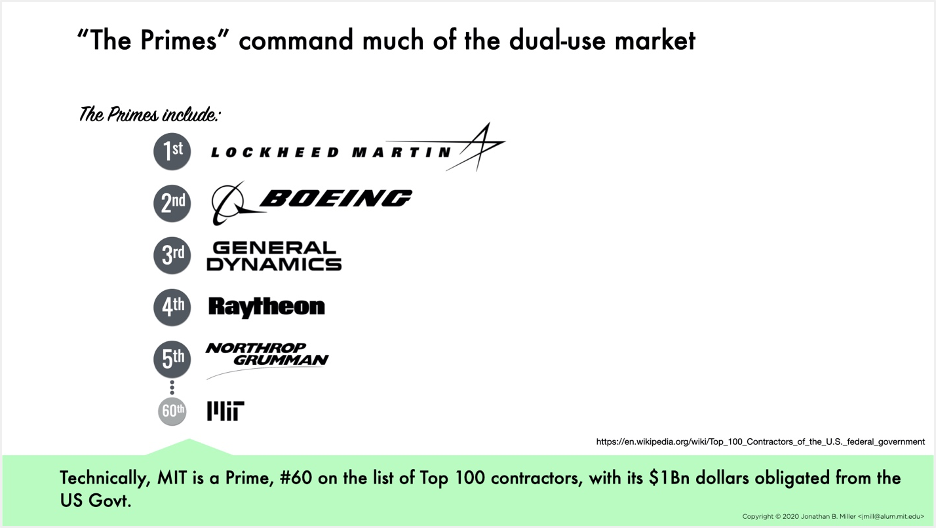

Finally, Washington needs to take steps to ensure that the financial interests of a handful of weapons contractors do not drive critical US arms export policy decisions. Of the $101 billion in major arms offers since the Biden administration took office, over 58 percent involved weapons systems produced by four companies: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, and General Dynamics.

The concentrated lobbying power of these companies — including a “revolving door” from the Pentagon’s arms sales agency and the leveraging of weapons export-related jobs into political influence — has been brought to bear in efforts to expand US weapons exports to as many foreign clients as possible, often by helping to exaggerate threats.

A number of policy measures can be taken to increase the prospects that major sales will serve broader US interests in peace and stability in key countries and regions, rather than undermine them:

- Restricting the revolving door between government and industry as a way to weaken the grip of weapons makers over arms transfer decision making.

- Making it possible for Congress to block dangerous weapons sales, through a revision to the Arms Export Control Act that would require an affirmative congressional vote on major deals — as opposed to the current system, which requires a veto-proof majority to block any arms sale.

- Providing greater transparency so Congress and the public know what sales are being made, when arms are being delivered, and how US arms are being used. Without this level of information, it is virtually impossible for Congress or the public to fully assess the risks and consequences of US arms transfers.

- Requiring better risk assessments by the Pentagon and State Department as to the likely impact of particular sales regarding arms race dynamics, fueling conflict, enabling of human rights abuses, or diversion of US-supplied arms into the hands of US adversaries, and hiring sufficient staff to carry out these analyses.

Introduction

This paper assesses the security impacts of the Biden administration’s approach to foreign arms sales. It takes into account the policies of prior administrations and the longstanding role of the United States as the world’s leading arms exporting nation.

Issues addressed include the role of US arms transfers in fueling conflict, enabling human rights abuses, and entangling the United States in unnecessary conflicts. The paper focuses particularly on transfers to Europe and Asia, in line with the “great power” focus of US national security strategy; the security impacts of ongoing sales to the Middle East; and a discussion of the counterproductive effects of an overly militarized US approach to counterterrorism policy in North Africa and the Sahel.

The role of weapons contractors in shaping — and profiting from — US arms sales are also addressed, including the role of Raytheon in pressing for arms sales to Saudi Arabia despite its devastating use of US weapons in Yemen. The paper concludes with recommendations on how to improve US arms policy so that it aligns with the country’s security interests, in part by reforming the arms sales decision making process.

The Biden Policy in Context

On arms sales, the Biden administration has shown more continuity than change relative to the policies of the prior two administrations. President Biden pledged during the 2020 presidential campaign that America would no longer “check its values at the door to sell arms.”2

In his first foreign policy speech, he pledged to end US support for offensive operations in Yemen, as well as relevant arms sales.3 The administration also suspended sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates pending a policy review, but aside from blocking one proposed bomb sale to Riyadh, its policy quickly reverted to the status quo ante.

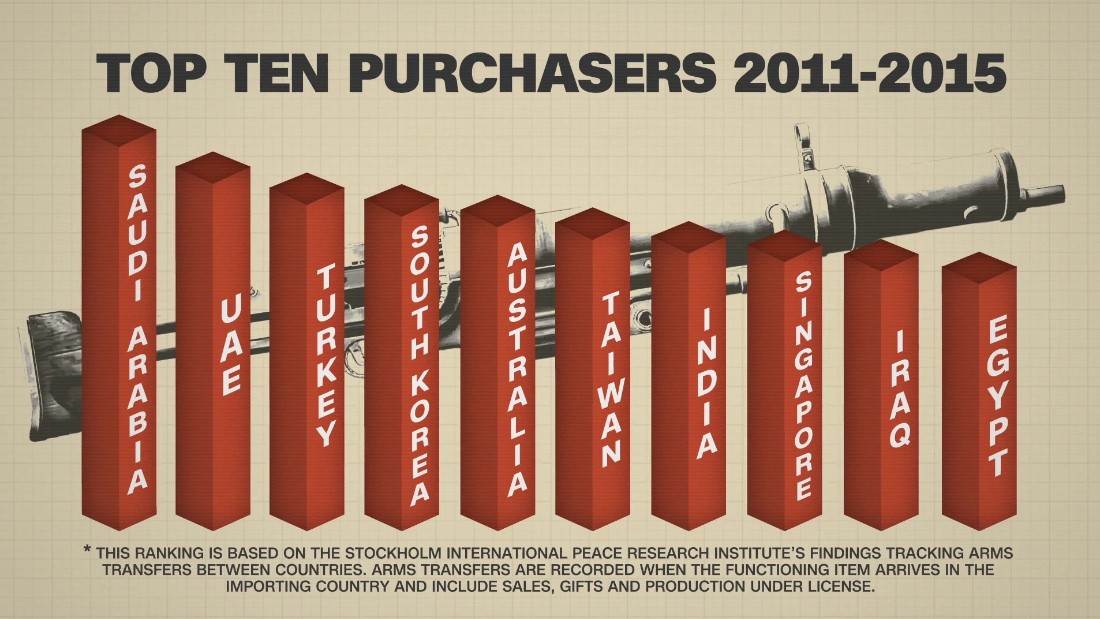

The Biden administration has continued to arm reckless, repressive regimes — like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Nigeria and the Philippines — that have acted in ways that undermine US interests and risk entangling the United States in unnecessary conflicts. The potential impacts of sales to each of these nations are outlined below.

In assessing any administration’s approach to arms transfers, it is important to note that the process of deciding on and supplying weapons can unfold over several years or more. This means that deals offered under one administration may have had their roots in a prior one. However, the specific offers to the countries cited above received final sign off during the Biden years, meaning that the administration can and should be held accountable for the potential impact of these sales.

The analysis of the impacts of arms sales is further complicated by the differences in the two main channels of arms supply — government-to-government sales under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) licensed by the State Department.

FMS offers give the US government more input into the terms of the deal and include follow-on support like arranging the provision of spare parts, but they also include a 3 percent administrative surcharge that some suppliers and recipients prefer to avoid.

Commercial sales involve direct negotiations between the supplying company and the recipient, offering the arms exporting firm more freedom to negotiate the price and to set the terms of supporting arrangements like co-production deals, which involve production of components of a weapons system in the recipient nation.4

Offers of major defense equipment under the FMS program are subject to detailed notifications to Congress that include the equipment offered, its anticipated dollar value, a brief description of its rationale, identification of the main contractors involved, and an indication of how many US personnel may be deployed to the recipient country in support of the sale.

By contrast, DCS authorizations are poorly and haphazardly reported. The weapons systems are described only as a part of broad categories, with no indication of which authorizations eventuate in final sales or deliveries to client nations. For most of the data included in this paper, the totals reflect only FMS deals. This channel includes most sales of major systems like military aircraft, armored vehicles, artillery, missiles, and combat ships.

US arms offers showed a sharp drop in the first year of the Biden administration, to $36 billion, down from $110.9 billion in the final year of the Trump administration.5 This drop may have been partly due to a less aggressive approach to arms sales promotion, but was more likely the consequence of market saturation caused by the huge volume of deals concluded during the Obama and Trump administrations.

Offers have shown a major uptick in 2022, to $65 billion as of October.6 This is due in part to increases in sales to Europe and Asia tied to the Pentagon’s focus on “great power competition” with Russia and China.

The administration’s approach to arms sales going forward might be clarified once it releases its long-delayed policy directive on the issue. At a minimum, the release of the document will offer an opportunity for additional congressional and public debate regarding the consequences of US weapons exports and what criteria should be used in deciding which nations to arm.

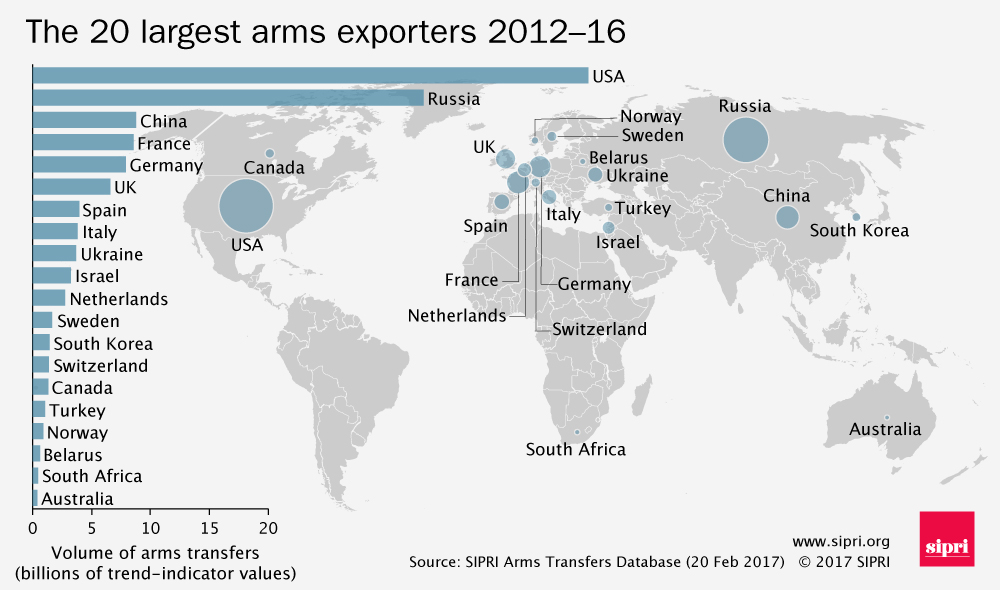

The US Role in the Global Arms Trade

The United States accounted for 39 percent of major weapons deliveries for the five-year period from 2017–21, according to figures compiled by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). This is twice as large as Russia’s share of the market, and over eight times China’s share.7

Arms sales can also pose risks to US security by fueling conflicts, provoking US adversaries, stoking arms races, and drawing the US into unnecessary or counterproductive wars.

Advocates of weapons exports promote sales by claiming they help US allies provide for their own defense, stabilize key regions, deter US adversaries, build US military-to-military relationships with current and potential partner nations, provide political and diplomatic influence, and create jobs in the United States.

But arms sales can also pose risks to US security by fueling conflicts, provoking US adversaries, stoking arms races, and drawing the US into unnecessary or counterproductive wars.

US sales can also enable human rights abuses by partner nations; these often provoke a backlash and increase the ability of terrorist groups to recruit. Too often, arms sales decisions are driven as much or more by the parochial interests of defense contractors as they are by security considerations.

Current US arms policy and practice too often fuel war rather than deterring it. Roughly two-thirds of current conflicts — 34 out of 46 — involve one or more parties armed by the United States.8 In some cases US arms sales to combatants in these wars are modest, while in others they play a major role in fueling and sustaining the conflict.

Of the US-supplied nations at war, 15 received $50 million or more worth of US arms between 2017 and 2021. This contradicts the longstanding argument that US arms routinely promote stability and deter conflict. While some US transfers are used for legitimate defensive purposes, others exacerbate conflicts, increase tensions, and fuel regional arms races.

There is a pronounced lack of transparency about the role of US arms in many of these wars, but the fact that US weapons are going to so many conflict zones is a concern in its own right, and demands better tracking of the precise role of US-supplied equipment.

Table 1: Countries at War that Received $50 Million or More of US Weapons between 2017 and 2021

| Country | Type of Conflict | Value of Arms Supplied (USD) |

| Afghanistan | Major War | $9.1 billion |

| Brazil | High Intensity | $221.9 million |

| Colombia | High Intensity | $232.8 million |

| Egypt | High Intensity | $3.7 billion |

| Israel | Low Intensity | $7.1 billion |

| Kenya | High Intensity | $168.3 million |

| Lebanon | High Intensity | $500.5 million |

| Mexico | Low Intensity | $90.5 million |

| Nigeria | Low Intensity | $503.9 million |

| Philippines | Low Intensity | $521.9 million |

| Saudi Arabia* | Major War | $34.5 billion |

| Thailand | Low Intensity | $753.7 million |

| Turkey | High Intensity | $724 million |

| UAE* | Major War | $9 billion |

| Ukraine** | High Intensity | $1.6 billion |

- Parties to war in Yemen | ** Figures prior to February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine | SOURCES: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI Yearbook 2022, chapter 2; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project; and US Department of Defense, Defense Security Cooperation Agency

Conflict intensity is defined as follows: major war, 10,000 or more fatalities in a year; high intensity war, 1,000 to 9,999 fatalities in a year; low intensity war, 25 to 999 fatalities in a year.

The United States also routinely sells to undemocratic regimes, many of which commit major human rights abuses. As of 2021, the most recent year for which full statistics are available, the US has provided weapons and training to 31 nations that Freedom House has defined as “not free.”9 Arming these kinds of governments runs contrary to the Biden administration’s commitment to support “democracy” over “autocracy.”

As Asli Bali noted in a Quincy Institute issue brief, “What is needed is not selective human rights conditionality but an end to arms sales to abusive regimes.”10 A number of cases where this approach may apply are outlined below.

A roster of the top recipients of US arms offers under the Biden administration is below.

US Arms Sales to Nations at War:

The Case of the Greater Middle East

While the center of gravity for US arms sales is beginning to shift from the Middle East to Europe and East Asia, the recent history of weapons transfers to the Middle East underscores the risk of using arms sales as a central instrument of foreign and military policies.

Not only do US arms sales fail to provide influence, as alleged, but they can destabilize entire regions and increase the risk of the United States being drawn, directly or indirectly, into conflicts that do not serve its strategic interests, or staying involved in conflicts long after US involvement has become counterproductive.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the War in Yemen

The Saudi-led intervention in Yemen has gone on for more than seven years, at great cost to human life and regional stability. The United States has been the primary weapons supplier to Saudi Arabia and the UAE — the two main players in a coalition that has been fighting the Houthi-led opposition in the Yemen war. The Houthi coalition is an indigenous political movement with longstanding grievances that predate the current war, not merely an Iranian proxy force, as is sometimes claimed.11

There was a fragile truce in the Yemen war that began in April of 2022, but it expired on October 2, raising fears of renewed fighting.12

Since 2015, the United States has provided tens of billions of dollars in arms and military support to the Saudi and UAE regimes, much of it for systems that have been used in Yemen. According to a June 2022 Government Accountability Office report, the United States administered over $54 billion in arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE from 2015 — the first year of the Yemen war — through 2021.13

For the five years from FY 2017 to FY 2021 — the period for which full breakdowns are available — sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE accounted for 17 percent of total sales under the US government’s Foreign Military Sales program.14

The consequences of the war in Yemen have been disastroUS More than 24,000 people have died in indiscriminate air strikes, including nearly 9,000 civilians, tied to the bombing of targets like marketplaces, water treatment facilities, hospitals, a school bus, a wedding, and even a funeral.15

Many of these attacks have been carried out by the Saudi Royal Air Force using US–supplied munitions and aircraft. According to a joint investigation by the Washington Post and the Security Force Monitor at Columbia Law School, “a substantial number of the raids were carried out by jets developed, maintained, and sold by US companies, and by pilots that were trained by the US military.”16

“For as many bad guys that we kill with this strategy, we create two more. Ultimately, our involvement is making the United States less safe as we create conditions that radicalize a generation of young Middle Easterners against US” — Sen. Chris Murphy

The toll of the war on the people of Yemen has gone well beyond the impact of the bombing campaign. A Saudi-led air and sea blockade has impeded the import of critical items like fuel, food and medical supplies, pushing Yemen to the brink of famine and resulting in the deaths of nearly 400,000 people.17 Not only has the Yemen war brought immense suffering, it has also sparked instability in the region and fostered resentment towards the United States that has undermined its ability to achieve its strategic objectives.

Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) has discussed the negative security impacts of US arms sales to Saudi Arabia:

“There is a US imprint on each of these civilian deaths. As the humanitarian nightmare worsens, it also provides the fuel to recruit young men into terrorist organizations such as al Qaeda and ISIS, which have been able to thrive in the power vacuum created by the war. For as many bad guys that we kill with this strategy, we create two more. Ultimately, our involvement is making the United States less safe as we create conditions that radicalize a generation of young Middle Easterners against US”18

Now that the truce in the Yemen war has ended, the United States must press Saudi Arabia and other involved parties to engage in good faith negotiations for a peace agreement. Toward that end, over 100 members of the House of Representatives are supporting a Yemen War Powers Resolution (WPR) introduced by representatives Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Peter DeFazio (D-OR).19

A companion measure has been introduced in the Senate by Senators Bernie Sanders (D-VT), Patrick Leahy (D-VT), and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA). The resolutions would stop US military support for Saudi Arabia, including spare parts and maintenance that sustain the Saudi war machine.

As Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA), a co-sponsor of the House WPR, has noted, “The clearest and best way to press all sides to the negotiating table is for Congress to immediately invoke its constitutional war powers to end US involvement in this conflict.”20

Now that the truce in the Yemen war has ended, the United States must press Saudi Arabia and other involved parties to engage in good faith negotiations for a peace agreement.

Despite these congressional initiatives and its own early statements on sales to the Gulf States, in July 2022 the Biden administration took a further step towards resuming and even expanding US military support for the Saudi regime when the president met with de facto Saudi leader Mohammed Bin Salman and pledged closer security ties.

The final communique from the meeting, which was held under the auspices of the Gulf Cooperation Council, made no new formal commitments but spoke of “deepening security ties” between the United States and its Gulf partners. It also affirmed the “United States’ commitment to its strategic partnership with GCC member states” and its pledge to “work jointly with its partners in the GCC to deter and confront all external threats to their security.”21

F-15 Eagles with the Royal Saudi Air Force.

Shortly after the president’s visit, on August 2, 2022, the Pentagon announced offers of missile defense systems to Saudi Arabia and the UAE worth over $5 billion in total. And in mid-July the administration announced an offer of sustainment services for the UAE’s US-supplied C-17 transport planes worth almost $1 billion (see appendix for details on sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE during the Biden administration).

There have also been reports that the administration might lift its suspension on the transfer of offensive weapons to Saudi Arabia, reports that administration officials have so far been denied but appear to be discussing internally.22 These reports come alongside the Biden administration’s continuing failure to define what it means by an “offensive” versus “defensive” weapons, as noted in a recent report by the Government Accountability Office.23

The distinction between offensive and defensive weapons can be hard to draw, as it can have as much to do with how the weapons are likely to be used as it does with the qualities of the weapons themselves.

The administration’s arms sales to the Gulf states come against the backdrop of efforts to strengthen a coalition of those nations with Israel, in part under the rubric of the Trump administration–sponsored Abraham Accords. These could just as easily be dubbed the “arms sales accords” given US weapons offers to the region since they were initiated in September 2020 Saudi Arabia is not a formal signatory to the accords but has moved closer to Israel in parallel to their creation.24

As Trita Parsi, Quincy Institute co-founder and executive vice president, has noted, this focus on arms sales over diplomacy could also undermine the future of the Iran nuclear deal and sideline prospects of an improvement of relations with Tehran:

“The United States cannot expect an arms control agreement with Iran to endure if it simultaneously seeks to expand the Abraham Accords into an anti-Iran military alliance and to provide ever more sophisticated weapons systems to Iran’s regional rivals. Cementing regional divisions and intensifying Iranian suspicions about its neighbors will only give Iran new incentives to cheat on the agreement and pursue a nuclear deterrent.”25

The administration’s “reset” of relations with Saudi Arabia is a far cry from Biden’s description of Saudi Arabia as a “pariah state” on the campaign trail.26 The new policy has been rationalized by a desire to encourage the Saudi regime to pump more oil to offset the impacts of sanctions on Russia, as well as a renewed impetus for building an alliance against Iran. As suggested above, more arms sales to Saudi Arabia are likely to flow from these new arrangements.

Saudi Arabia is extremely unlikely to increase its oil exports in response to requests from the Biden administration.27 In fact, in September of 2022, OPEC — in which Saudi Arabia wields substantial influence — announced that it would be reducing oil output. Saudi Arabia has also been purchasing oil from Russia in contravention of sanctions on Moscow tied to its invasion of Ukraine.28

In early October, the Saudi government joined hands with Russia to push through a greater reduction in oil production likely to increase inflation in energy prices in the United States and globally.

As Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) and Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) noted in an essay co-authored with Jeffrey Sonnenfeld of the Yale School of Management, “The Saudi decision was a pointed blow to the US, but the US also has a way to respond: It can promptly pause the massive transfer of American warfare technology into the eager hands of the Saudis.”29

The Biden administration has pledged that there will be “consequences” due to Saudi collaboration with Russia on oil output, but it has yet to specify what those consequences may be.30

It is not clear whether the current controversy over arming Saudi Arabia will impact the administration’s efforts to use arms sales to facilitate the creation of a political and military bloc against Iran centered on Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Creating such a bloc will only increase the risks of a war with Iran while undermining diplomatic efforts, brokered by Iraq, to cool tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

The arms industry has mounted a concerted effort to tilt US policy toward selling the full spectrum of US weapons to Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

For its part, the UAE has been the primary partner of Saudi Arabia in the Yemen war, but its role has received considerably less attention. In February 2020, the UAE announced that it had pulled most of its troops out of Yemen, but it continues to arm, train and back militias involved in the war, which total 90,000 members in all.

The UAE–backed militias have been implicated in abuses ranging from indiscriminate artillery shelling to torture to recruitment of child soldiers.31 The UAE has also enforced a de facto occupation of Socotra Island, a Yemeni possession in the Gulf of Aden, establishing a strong political and economic presence there and setting up a military base in pursuit of potential control over vital sea traffic and expanding its already considerable influence in the Horn of Africa.32

Giorgio Cafiero of Gulf State Analytics has summarized UAE’s role on Socotra:

“Socotra has become an Emirati possession in all but name, with the UAE seeking to systematically separate it from Yemen and run it as its own territory.33

In addition to issues related to the war in Yemen, selling arms to the UAE endorses or enables its reckless conduct in the Middle East and North Africa, including its role in arming the opposition forces of Gen. Khalifa Hiftar in Libya in violation of a UN arms embargo.34

The arms industry has mounted a concerted effort to tilt US policy toward selling the full spectrum of US weapons to Saudi Arabia and the UAE (see section below on Raytheon’s lobbying for bomb sales to Saudi Arabia).

In addition to the risk of further embroiling the United States in current and potential Middle East conflicts, US arms transferred to the region also frequently end up inadvertently in the hands of US adversaries, where they may be used against US allies or even US military personnel.

Examples include Yemen, where the Pentagon lost track of $500 million in weapons supplied to the dictatorship of Ali Abdullah Saleh.35 The arms were believed to have ended up either with Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula or the Houthi-led opposition that has been fighting the US-backed Saudi-UAE coalition that invaded Yemen in March 2015.

In addition, as CNN and independent analysts have documented, the UAE transferred US-supplied weapons — including Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles — to extremist militias fighting in Yemen.36 The UAE suffered no consequences for its mishandling of the US weapons, despite the fact that the transfers violated US law.

William D. Hartung is Senior Research Fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and an expert on the arms trade, Pentagon spending and strategy, and nuclear weapons policy. His books include Prophets of War: Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex.

Note: Read the entire essay online for assessments about arms sales to Egypt, Israel, Asia, Taiwan, Australia, Japan, Korea, The Philippines, Nigeria, Sahel, Saudi Arabia.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.