In the Pacific, Outcry Over Japan’s

Plan to Release Fukushima Wastewater

.

Pete McKenzie / The New York Times

(December 30, 2022) — Every day at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan, officials flush over a hundred tons of water through its corroded reactors to keep them cool after the calamitous meltdown of 2011. Then the highly radioactive water is pumped into hundreds of white and blue storage tanks that form a mazelike array around the plant.

For the last decade, that’s where the water has stayed. But with more than 1.3 million tons in the tanks, Japan is running out of room. So next year in spring, it plans to begin releasing the water into the Pacific after treatment for most radioactive particles, as has been done elsewhere.

The Japanese government, saying there is no feasible alternative, has pledged to carry out the release with close attention to safety standards. The plan has been endorsed by the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog.

But the approach is increasingly alarming Japan’s neighbors. Those in the South Pacific, who have suffered for decades from the fallout of a US nuclear test in the Marshall Islands, are particularly skeptical of the promises of safety. Last month, a group representing more than a dozen countries in the Pacific, including Australia and the Marshall Islands, urged Tokyo to defer the wastewater releases.

Now, Japan is poised to forge ahead even as it risks alienating a region it has tried in recent years to cultivate.

Nuclear testing in the Pacific “was shrouded in this veil of lies,” said Bedi Racule, an antinuclear activist from the Marshall Islands. “The trust is really not there.”

Much of that mistrust is rooted in the unlikeliest of events. In 1954, snow fell on the tropical atoll of Rongelap. Residents of the reef, in the Marshall Islands, had never seen such a thing. Children played in it; some ate it. Two days later, US soldiers arrived to tell them the “snow” was actually fallout from America’s largest nuclear test, which took place on nearby Bikini Atoll and irradiated Rongelap after an unexpected change in wind direction.

The proposal has angered many of Japan’s

neighbors who will face exposure to

dangerous levels of radiation

In the test’s aftermath, hundreds of people suffered intense radiation exposure, leading to skin burns and pregnancy complications. Decades later, people of the Marshall Islands still feel its impact through forced relocations, lost land and heightened cancer rates. “You feel this deep sorrow,” Ms. Racule said. “Why were we not good enough to be treated like human beings?”

The people of the Marshall Islands were not the only ones affected. Twenty-three Japanese fishermen were sailing near Rongelap at the time. All suffered intense radiation sickness, and one died six months later as a result.

Their exposure led to Japan’s first large antinuclear protests.

“The whole antinuclear movement here in Japan came from the huge public mass actions after the Bikini Atoll testing,” said Meri Joyce, an antinuclear organizer at the Japanese activist group Peace Boat.

When asked about Pacific nations’ concerns, a representative for the Japanese Foreign Ministry said that as the only country to have suffered from atomic bombings in war and given its connection with the 1954 test, Japan empathized with their fears around radiation exposure.

That shared history and experience of nuclear exposure has contributed to some Pacific activists’ sense of betrayal. “Our Japanese friends and partners in the nuclear movement have been really fighting hard,” Ms. Racule said. “It feels like such a huge injustice.”

In a statement last year, Youngsolwara Pacific, a prominent environmental advocacy group, asked, “How can the Japanese government, who has experienced the same brutal experiences of nuclear weapons in both Hiroshima and Nagasaki, wish to further pollute our Pacific with nuclear waste? To us, this irresponsible act of trans-boundary harm is just the same as waging nuclear war on us as Pacific peoples and our islands.”

Pacific nations’ current frustration comes a year after Japan announced a “Pacific Bond” policy. The prime minister at the time, Yoshihide Suga, promised to take stronger action on climate change and to strengthen relationships with Pacific nations in what appeared to be an attempt to push back on growing Chinese influence in the region.

To soothe Pacific concerns, Japanese authorities emphasize that their analysis shows that the wastewater plan is safe. Almost all radioactive particles will be removed from the wastewater before it is released, except for a hydrogen isotope called tritium that Japanese experts and others say poses a relatively low health risk.

“By diluting the tritium/water mixture with regular seawater, the level of radioactivity can be reduced to safe levels comparable to those associated with radiation from granite rocks, bore water, medical imaging, airline travel and certain types of food,” Nigel Marks, a nuclear materials researcher and associate professor at Curtin University, said in a statement distributed by the Australian Science Media Centre.

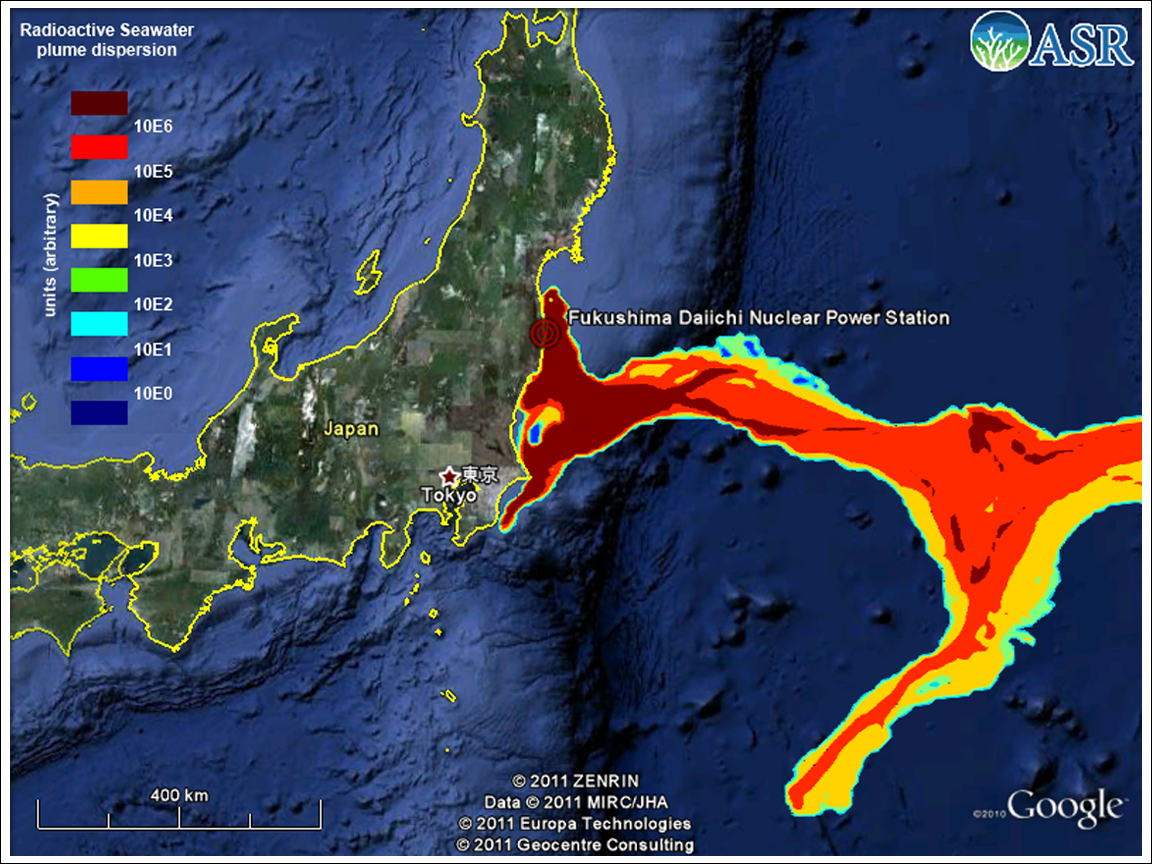

Projected path of radioactive water across the Pacific.

Mr. Suga pledged to “do our utmost to keep the water far above safety standards.” The Japanese government sees no alternative to the releases other than vaporizing the wastewater, which would be similarly controversial. Storage is becoming difficult as land runs short around the Fukushima plant, whose reactors have been off-line since the earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, which caused a catastrophic electrical failure that led to the meltdown.

Rafael Mariano Grossi, the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, has said the plan “is in line with practice globally, even though the large amount of water at the Fukushima plant makes it a unique and complex case.”

“The release of wastewater from the Fukushima reactors is an unfortunate necessity,” Brendan Kennedy, a chemistry professor at the University of Sydney, said in the Australian group’s statement. “The volume of contaminated water makes long-term storage of this impractical.”

Other nuclear plants around the world routinely discharge treated wastewater containing tritium. Unlike other common radioactive particles, tritium replaces the hydrogen atoms in water molecules, allowing it to pass unaffected through normal radiation filters. As a result, according to Dr. Kennedy, it is “essentially impossible” to remove.

The efforts to win over skeptical Pacific leaders have not been helped by a previous lack of transparency. Until 2018, Tokyo Electric Power Company — which operates the Fukushima plant — indicated that the vast majority of the wastewater had already been treated. That year, however, the power company acknowledged that only a fifth had been treated sufficiently.

The Japanese Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry subsequently said more than three-quarters of the wastewater still contained unsafe levels of radioactive material other than tritium because the company had not changed the decontamination system’s filters frequently enough. The company has promised to re-treat the wastewater before it is released.

Consequently, many in the Pacific remain suspicious. In its most recent request that Japan defer the planned releases, the Pacific Islands Forum, the region’s main diplomatic body, noted that a panel of experts it had appointed to scrutinize the plan said there was “insufficient data” to prove its safety.

Motarilavoa Hilda Lini, a prominent politician and activist in Vanuatu, has said, “We need to remind Japan and other nuclear states of our Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement slogan: If it is safe, dump it in Tokyo, test it in Paris, and store it in Washington, but keep our Pacific nuclear-free.”

The Japanese Foreign Ministry’s representative indicated that the government expects to proceed with the planned releases, subject to safety confirmation by the power company and the I.A.E.A. Last year, Mr. Suga, the former prime minister, said disposing of the wastewater was “a problem that cannot be avoided.”

But it seems increasingly likely that solving that problem will jeopardize Japan’s efforts to build closer bonds with its Pacific neighbors and exert greater influence in an increasingly contested region.

“It feels like such a huge injustice,” Ms. Racule said. “It’s almost like an arrogant display. That it doesn’t matter what we say, they still do what they want.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.