“Camp Justice” has become a monument to injustice.

I Survived Guantánamo.

Why Is It Still Open 21 Years Later?

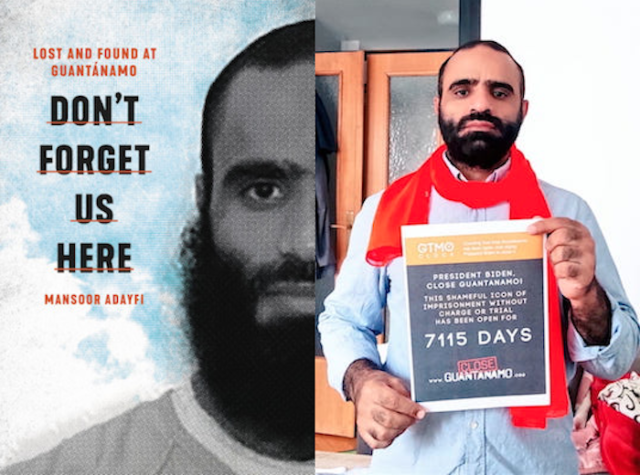

Mansoor Adayfi / The Guardian

(January 11, 2023) — The US prison at Guantánamo Bay opened 21 years ago this Wednesday. For 21 years, the extrajudicial detention facility has held a total of 779 men between eight known camps. In two decades, Guantánamo grew from a small, makeshift camp of chainlink cages into a maximum-security facility of cement bunker-like structures that costs close to $540m a year to operate.

Twenty-one years is a long time – a generation was born and came of age in that time. Four American presidents have served. The World Trade Center was rebuilt.

During that time, the US military, the CIA and other intelligence agencies experimented with torture and other human rights violations. Soldiers and even leaders committed war crimes. The US Congress researched, wrote and released a report documenting torture, abuse and inhumane treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo and at black sites around the world, while also making it impossible to close Guantánamo.

Of those 779 prisoners held at Guantánamo, we know that nine died there; 706 have been released or transferred out; 20 have been recommended for transfer but remain there; 12 have been charged with crimes; two have been convicted; and three will be held in indefinite law-of-war detention until someone demands their release.

I was 19 when I was sent to Guantánamo, I arrived on 9 February 2002, blindfolded, hooded, shackled, beaten. When soldiers removed my hood, all I saw were cages filled with orange figures. I had been tortured. I was lost and afraid and confused. I didn’t know where I was or why I had been taken there. I didn’t know how long I would be imprisoned or what would happen to me. No one knew where I was. I was given a number and became suspended between life and death.

I didn’t know a lot about America. I knew it was supposed to be a land of laws and opportunity. Everyone wanted to live there. We all believed our detention would be short. We hadn’t done anything. They couldn’t keep us long without someone caring. I never could have imagined that I would spend eight years in solitary confinement, that I would be held for 15 years and released without ever being charged with a crime.

I turned 40 recently, and even though I am a grown man I still feel like the 19-year-old who first arrived at Guantánamo. In one sense, I came of age there – learning how to protest my detention, how to use my body to hunger strike, how to resist. I think about my time there a lot. While my childhood friends went to university, married, got jobs and began their lives, I fought prison guards who harassed me while I tried to pray.

In Guantánamo’s early days, when it was just an undeveloped prison, a baby really, we all had questions: when would we be released? Why were interrogations getting worse? Why didn’t anyone believe what we told them? But we weren’t the only ones with questions. Young guards wanted to know what they were doing there, who we were, and why some leaders said we were the “worst of the worst” terrorists while other leaders called us nobodies or dirt farmers.

I think Guantánamo itself had the same questions. I think Guantánamo wanted to know what kind of place it would become, how long it would be used, if it would be useful.

We all waited for those answers, year after year, as we grew older. I grew a beard and my hair turned gray. Guantánamo rusted, peeled, decayed; Camp X-Ray, the first camp, became overgrown with weeds and grass. Guards rotated out and so did camp leaders. Guards who were kind to us were often demoted or punished or left Guantánamo confused about the conflict between their official duty and what they knew was right and wrong. General Miller, the architect of what the US calls “enhanced interrogation” and everyone else calls torture, went to Iraq and Abu Ghraib. Some prisoners were released. Some – like Yassir (21 years old), Ali (26), and Mani (30) – died violently and mysteriously in custody.

The years passed like chapters in a book, and with each new chapter we thought our questions would be answered or at least that the chapters would change. There were new beginnings and new phases, but the story remained the same: interrogations continued. So did our inhumane treatment and religious harassment.

Each chapter grew darker as we lost touch with the stories of our lives before Guantánamo. When we were taken to Guantánamo, we were fathers, sons, brothers, and husbands; we had families, dreams, and lives in the outside world. But at Guantánamo we were just numbers, animals in cages, totally cut off from the world we knew; we were caught in an endless loop of interrogations trying to get us to admit that we were al-Qaeda or Taliban fighters. We lived Guantánamo’s lawlessness and abuses, we watched Guantánamo grow and evolve, while our story remained stuck.

We became Guantánamo and so did our stories. We resisted and protested our arbitrary and indefinite detention, we fought and went on hunger strikes to make the world hear us, see our suffering, and know our humanity. We also had moments of happiness, creativity, and brotherhood. We sang, danced, joked and laughed. We created art. We became brothers and friends, even with some of the guards and camp staff who treated us like we were human. We gradually lost touch with our old selves until Guantánamo became our life, our world, our only story.

As Guantánamo grew older, stronger, and more permanent, we grew older, too, but weaker, more fragile, still bound within its cages. We heard that some people around the world protested our imprisonment and our torture and campaigned to close Guantánamo. That gave us hope and made us feel that we had not been forgotten. But others, like politicians outside of Guantánamo, learned to use the prison to create their own false stories – stories that feasted on us to create fear. They kept Guantánamo open.

Toward the end of my time, Guantánamo had grown, in some respects, more mature and more open. We had changed too; we had reconnected with the outside world. We tried to reclaim those parts of ourselves that had been taken away and lost. I took classes and created art. I learned English and wrote stories about Guantánamo. After 15 years, I worried that I wouldn’t survive in the world once I left. I had grown up there and become a man. Guantánamo is what I knew. It’s where my friends were.

I thought that by leaving, I would finally be able to write new chapters, ones that changed and had a good ending. I would end the story the way I wanted to: Guantánamo would become just a memory; I would move on, go to school, get married, start my life. But the prison didn’t want to let go. It surprised me with a new story.

Like me, hundreds of men have been released from Guantánamo. Some went home to their countries and to their families. Many were sent to places they don’t know – Uruguay, Kazakhstan, Slovakia. I was sent to Serbia, where I didn’t have friends or family and didn’t speak the language. We have tried to create our own stories in these new places, ones without Guantánamo. But Guantánamo won’t let us go. We live with the stigma of having been held there.

Thirty-five men remain there. President Biden has quietly worked to wind down the prison camp, but without cooperation from the US Congress, Guantánamo will remain open.

For years now, former prisoners, activists, lawyers and journalists have been working to write Guantánamo’s final chapter, one that ends with justice, accountability, reconciliation, and the closure of the prison. Let’s make that happen, so that in one year, we can write a new story about life after Guantánamo.

Mansoor Adayfi is an artist, advocate, and former Guantánamo prisoner, released in 2016 after being detained without charge or trial for more than 15 years. He is the author of the memoir Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.