/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-mco.s3.amazonaws.com/public/43BOMZ4LIRBTBCLAYBSBDQPMOY.jpg)

NATO to Surge Troops to Russian Border

Andre Damon / World Socialist Web Site

(April 18, 2023) — NATO plans to surge troops to Russia’s border as part of an effort to become a “war-fighting alliance,” the New York Times reported Monday.

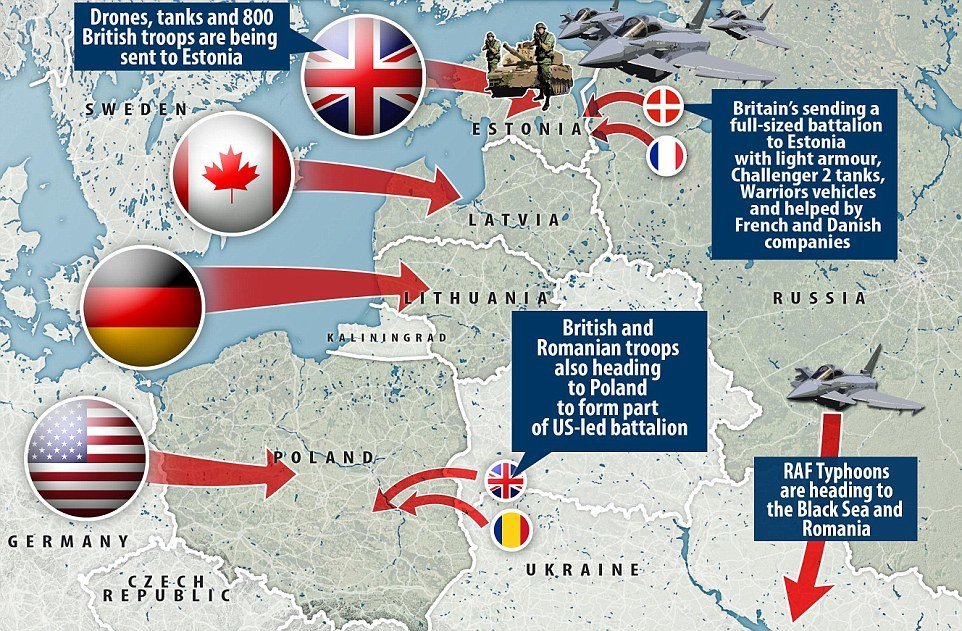

The Times wrote that “NATO now has deployed a battalion of multinational troops to eight countries along the eastern border with Russia. It is detailing how to enlarge those forces to brigade strength in those frontline states.”

A battalion can include up to 1,000 troops, while a brigade can include up to 5,000 troops, meaning that NATO could potentially plan to increase the number of troops on Russia’s borders fivefold, to up to 40,000 troops.

The Times reports that NATO “is also tasking thousands more forces, in case of war, to move quickly in support, with newly detailed plans for mobility and logistics and stiffer requirements for readiness.”

Politico, meanwhile, has cited even larger numbers. On March 18, it reported, “In the coming months, the alliance will accelerate efforts to stockpile equipment along the alliance’s eastern edge and designate tens of thousands of forces that can rush to allies’ aid on short notice… The numbers will be large, with officials floating the idea of up to 300,000 NATO forces.”

“The North Atlantic Treaty Organization,” wrote the Times, has launched “a full-throttled effort” to prepare for military operations all along its eastern flank.

As the Times put it, this “means a revolution in practical terms: more troops based permanently along the Russian border,” It also means “more integration of American and allied war plans, more military spending and more detailed requirements for allies to have specific kinds of forces and equipment to fight, if necessary, in pre-assigned places.”

The alliance has “shed remaining inhibitions about increased numbers of Western troops all along NATO’s border with Russia,” the Times stated. The aim is “to make NATO’s forces not only more robust and more capable but also more visible to Russia.”

Additional troops will be placed under the direct authority of Gen. Christopher G. Cavoli, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe, who also commands American forces in Europe, as part of the NATO alliance’s decision.

The Times reports that General Cavoli is integrating American and allied war-fighting plans for the first time since the Cold War. Citing a NATO official, the newspaper wrote, “Americans are back at the heart of Europe’s defense … deciding with NATO precisely how America will defend Europe.”

This will entail a massive military buildup, involving enormous increases in military spending. “Now the demands will be tougher and more rigorous to bring the alliance back to a war-fighting capacity in Europe and make deterrence credible—to ensure that NATO can fight a high-intensity war against a rival, Russia, from the first day of conflict,” the Times wrote.

Instead of meeting the previous goal of 2 percent of gross domestic product devoted to the military, NATO members will be expected to spend between 2.5 and 3 percent, the Times reported.

In perhaps the most ominous passage in the article, the Times wrote, “Previously, the annual exercises of NATO’s nuclear forces, known as Steadfast Noon, were kept quiet. But last year, after Russia’s invasion, the exercise went ahead openly. It was important, a NATO official said, to show Moscow that the alliance wasn’t deterred by nuclear threats.”

NATO’s headquarters is likewise “being transformed into a major strategic and war-fighting command, charged with drawing up the alliance’s plans to integrate and deploy allied troops.”

The accession of Finland to NATO, which doubled the length of NATO’s land border with Russia, will be a key component of these plans, with Russia’s entire border with NATO becoming a militarized zone.

Just weeks after its accession to NATO, Finland has begun building a fence on the Russian border, with the initial section to be completed in June.

In June of last year, NATO published a strategy document declaring that the alliance must prepare for “high-intensity, multi-domain warfighting against nuclear-armed peer-competitors.” The document declared that “the Euro-Atlantic area is not at peace”—all but declaring that the alliance is at war.

In January, Rob Bauer, NATO’s top military spokesperson, declared that the US-led NATO alliance is prepared for a “direct clash with Russia.” Asked by Portugal’s RTP News, “You don’t believe that it’s only about Ukraine?” Bauer replied, “No, it’s about turning back to the old Soviet Union.”

The interviewer continued, “So the entire Eastern Flank is at risk somehow?” Bauer replied, “Yeah.” The interviewer asked, “We are ready to [sic] a direct confrontation with Russia?” To this Bauer replied, “We are.”

In this supercharged environment, NATO will begin Defender 23, the alliance’s annual war game, on April 22.

The exercise will involve 9,000 US troops and 17,000 soldiers from other NATO members. The “nearly two-month-long exercise is focused on the strategic deployment of US-based forces, employment of Army pre-positioned stocks and interoperability with European allies and partners,” a Pentagon spokesperson said April 5.

A key goal of the exercise will be to “increase lethality of the NATO Alliance through long-distance fires” according to US Army’s Europe and Africa commands.

This will be followed by Air Defender 2023, the largest NATO air exercise since its founding. A US Air National Guard official told the War Zone that Russian officials can “take away whatever message they want” from the drill.

Against this background, a group of former top officials from France, Germany, the United States and Spain have written an op-ed in the Guardian Sunday encouraging more direct NATO military intervention against Russia, declaring “We have to go ‘all in’ in our support for Ukraine.” They declare that “Ukraine needs the combined force of tanks, longer-range missiles and aircraft to conduct a successful counterattack, paving the way to Ukrainian victory.”

The press is full of such declarations. David Ignatius, writing in the Washington Post, argued, “President Biden doesn’t want to start World War III, but he will look back with regret if the United States and its allies leave any weapons or ammunition on the sidelines that could responsibly be used in this conflict. Whatever Biden might wish later he had done if things go badly, he should do now.”

As the deteriorating military situation for the Ukrainian armed forces becomes increasingly apparent, NATO is making open plans to massively intensify its conflict with Russia.

Militarism, NATO, and Ukraine Geopolitics:

Exploring Myths and Realities

David Swanson, Bob Fantina and Khawaja Hammad Akbar / Global Times Pakistan

With Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine, NATO Readies for Combat on Its Borders

Steven Erlanger / The New York Times

(April 17, 2023) — Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the costliest conflict in Europe since World War II, has propelled the North Atlantic Treaty Organization into a full-throttled effort to make itself again into the capable, war-fighting alliance it had been during the Cold War.

The shift is transformative for an alliance characterized for decades by hibernation and self-doubt. After the recent embrace of long-neutral Finland by the alliance, it also amounts to another significant unintended consequence for Russia’s president, Vladimir V. Putin, of his war.

NATO is rapidly moving from what the military calls deterrence by retaliation to deterrence by denial. In the past, the theory was that if the Russians invaded, member states would try to hold on until allied forces, mainly American and based at home, could come to their aid and retaliate against the Russians to try to push them back.

But after the Russian atrocities in areas it occupied in Ukraine, from Bucha and Irpin to Mariupol and Kherson, frontier states like Poland and the Baltic countries no longer want to risk any period of Russian occupation. They note that in the first days of the Ukrainian invasion, Russian troops took land larger than some Baltic nations.

To prevent that, to deter by denial, means a revolution in practical terms: more troops based permanently along the Russian border, more integration of American and allied war plans, more military spending and more detailed requirements for allies to have specific kinds of forces and equipment to fight, if necessary, in pre-assigned places.

Mr. Putin has long complained about NATO encirclement and encroachment. But his invasion of Ukraine provoked the alliance to shed remaining inhibitions about increased numbers of Western troops all along NATO’s border with Russia.

The intention is to make NATO’s forces not only more robust and more capable but also more visible to Russia, a key element of deterrence.

“The debate is no longer about how much is too much,” for fear of upsetting Moscow, “but how much is enough,” said Camille Grand, until recently NATO’s assistant secretary general for defense investment, and now with the European Council on Foreign Relations.

The countries of Central and Eastern Europe insist that it is “no longer enough to say we’re ready to deter by promising to reconquer, but that we need to defend every inch of NATO territory from day one,” said Mr. Grand. “It’s not okay to be under Russian control for a few months until the cavalry arrives.”

American soldiers engaged in firing artillery during an exercise at the Mihail Kogalniceanu Air Base in Romania.

NATO now has deployed a battalion of multinational troops to eight countries along the eastern border with Russia. It is detailing how to enlarge those forces to brigade strength in those frontline states to enhance deterrence and be able to push back invading forces from the start. And it is also tasking thousands more forces, in case of war, to move quickly in support, with newly detailed plans for mobility and logistics and stiffer requirements for readiness.

“NATO is an organization that took a holiday from history,” said Ivo H. Daalder, a former American ambassador to NATO. Mr. Putin, he said, “reminded us that we have to think about defense and think about it collectively.”

The alliance will put more troops under the direct control of NATO’s top military officer, the supreme allied commander Europe, Gen. Christopher G. Cavoli, who also commands American forces in Europe.

Under a new rubric of “deter and defend,” General Cavoli is for the first time since the Cold War integrating American and allied war-fighting plans, a senior NATO official said, speaking anonymously because of the topic’s sensitivity. Americans are back at the heart of Europe’s defense, he said, deciding with NATO precisely how America will defend Europe.

For first time since the Cold War, the official said, East European countries will know exactly what NATO intends to do to defend them — what each country should be able to do for itself and how other countries will be tasked to help. And Western countries in the alliance will know where their forces need to go, with what and how to get there.

NATO is also aligning its longer-term demands from allies with its current operational needs. If in the past NATO countries might be asked to send some lightly armed expeditionary forces with helicopters to Afghanistan, for instance, now they will be tasked to defend particular parts of NATO territory itself.

For Britain, just one example, that will mean that it provide more heavy armor to defend NATO’s eastern flank, even if the British government would prefer to continue to field a lighter, more expeditionary army, requiring less money, fewer people and less expensive heavy equipment.

The planning in NATO is already intrusive but will become more demanding and specific. Countries answer questionnaires about their capacities and equipment; NATO planners tell them what’s missing or could be cut or thinned.

In one case, said Robert G. Bell, defense adviser to the American mission at NATO until 2017, Denmark was told to stop wasting money building submarines. Canada was told it must provide air-refueling planes.

Countries can push back — for years some nations with frigates refused to put air-defense missiles on them for fear of seeming escalatory — but they must defend their plans before all NATO members. If the other allies all agree that a country’s plan is inadequate, they can vote to force adaptation in what is known as “consensus minus one.” Such a demand is rare, but happened with Canada, Mr. Bell said.

Now the demands will be tougher and more rigorous to bring the alliance back to a war-fighting capacity in Europe and make deterrence credible — to ensure that NATO can fight a high-intensity war against a rival, Russia, from the first day of conflict.

The change at NATO began slowly in 2014 after Russia annexed Crimea, igniting insurrection in the eastern Donbas. At their summit that year in Wales, NATO allies agreed on a goal for military spending of 2 percent of gross domestic product by 2024. At the moment, only eight of 31 countries, including new member Finland, met that goal, but military spending has increased significantly, up $350 billion since 2014.

At the next NATO summit this July, a new spending plan will be agreed, with 2 percent of G.D.P. regarded as a minimum. Given Russia’s difficulties in Ukraine, if major countries spend between 2.5 percent and 3 percent of G.D.P. on the military over the next decade, that should be sufficient, the senior NATO official said.

After 2014, NATO also agreed to put four small battalion-sized forces in the Baltic States and Poland. The idea was to engage invaders and hope to get reinforcements in place a week or two after an invasion.

After Russia’s invasion last year, NATO added four more forward-based battalions, to make eight such forces along NATO’s eastern edge, now including Romania, Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria. But the total troop number for all eight battle groups is only 10,232, NATO says.

NATO now is planning how to scale up to brigade-sized forces, meaning putting about 4,000 to 5,000 troops in each country to make NATO’s enhanced deterrence “a more robust tripwire,” Mr. Bell said.

That will also mean improving NATO’s air defenses — a major shortcoming from the shrinking militaries of the last 30 years, when few imagined Russian missiles raining down on Europe — and more numerous and elaborate troop exercises, visible to Moscow.

US troops pour into military base in Romania.

Previously, the annual exercises of NATO’s nuclear forces, known as Steadfast Noon, were kept quiet. But last year, after Russia’s invasion, the exercise went ahead openly. It was important, a NATO official said, to show Moscow that the alliance wasn’t deterred by nuclear threats.

NATO’s military headquarters, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, is also being strengthened.

The thousands of allied soldiers working there are being transformed into a major strategic and war-fighting command, charged with drawing up the alliance’s plans to integrate and deploy allied troops — including cyber, space and maritime forces — in various contingencies. Those can range from planning a hybrid war to a regional war that spirals out of control to an all-out conflict involving nuclear weapons.

The NATO command needs to figure out how to incorporate Finland and likely Sweden, and decide where their forces must commit to collective defense. For instance, should Finland be part of the headquarters that covers the Baltics or the one that covers the Arctic routes and the High North, or both?

In principle, NATO’s leadership can call on 13 corps of 40,000 to 50,000 troops each to fight if necessary. But NATO’s actual, deployable strength is nowhere near that, senior NATO officials concede. So General Cavoli and his team must figure out how best and where to deploy what is really available in a crisis, while trying to ensure that countries continue to improve their readiness.

One of the least glamorous challenges is, simply speaking, mobility and logistics: getting troops and tanks and guns where they need to be as quickly as they need to be there, and sustaining them.

Right now there are major post-Cold War roadblocks that include lack of storage, lack of suitable rail cars, lack of emergency rights of way to cross borders and use of roadways, issues that involve decisions by civilian authorities.

But even supplying Ukraine from a peaceful Poland is proving a major logistical headache, said another NATO official, who also spoke on the topic under condition of anonymity. Trucks are backed up with supplies, there’s a shortage of railway cars that can carry heavy equipment like tanks, and permissions must be obtained at every European border. Doing it in a shooting war, he said, with missiles flying, bombs dropping, the Internet crashing and refugees racing in the other direction, is another challenge entirely.

“NATO didn’t think seriously about defending its own territory and now it must,” said Mr. Daalder, president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. It did that for 40 years, and even if the muscles have atrophied, the muscle memory is there, he said. “The key is to have people and governments who never lived through this, learning how to do it.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.