The centrality of militarism

in 18th-century Britain and how

imperial expansion and arms went hand in hand

Emma Griffin / The Guardian

(July 13, 2018) — Ever since Arnold Toynbee invented the term the “industrial revolution” in the late 19th century, historians have been fascinated by the concept. In recent times, much scholarly attention has been paid to what caused it: plentiful coal supplies, Britain’s peculiar inventiveness, consumerist desires, empire, slavery, high wages, a stable state — all have had their advocates as the key force that underpinned our nation’s experience as the “workshop of the world”.

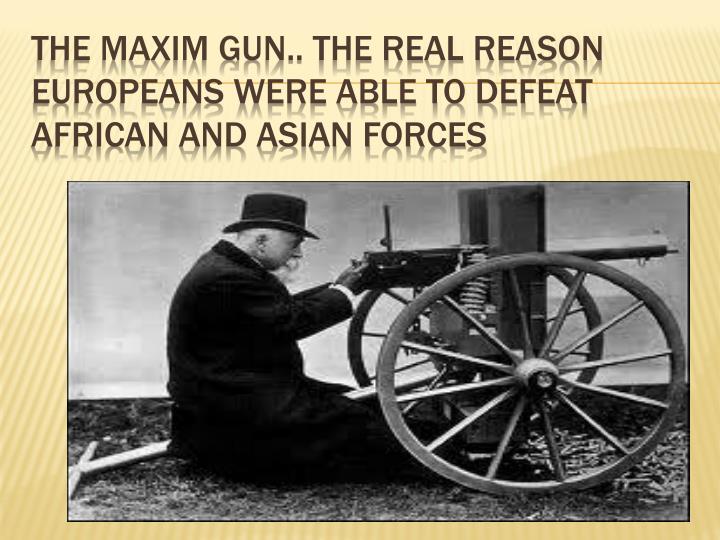

Priya Satia’s argument is that war “stimulated industrial resourcefulness” — that the government’s demand for military equipment “drove substantive progress in heavy metal industries, steam power, and textiles.” Britain’s warmongering and gun-making industries were not simply part of the industrial revolution, they caused it. This approach faces the same difficulties as all other monocausal explanations of a phenomenon that was varied and complex. But read as a study of guns, violence and empire, this book is a triumph.

From her research into the Birmingham gun-making industry, she can show myriad ways in which war was good for business: “Whatever 18th-century industrial business you were in, you probably made something the government needed for war.” And what’s more, the British government was likely to pay its debts.

This study’s most original contribution lies in its insights about the place of guns in British cultural and colonial expansion. In the 18th century, both in Britain and elsewhere, they had a range of different meanings and uses — as status symbols, as gifts, as currency, as signifiers of power. In this era, most violence was perpetrated without the use of a gun and most guns were used to protect property. Imperial expansion was, of course, “fundamentally about seizure of land … the imperialist gathered the confidence to make that seizure by displaying his gun before the native inhabitant”.

The final section of the book returns from the colonies, back to Birmingham, and the specific problems faced by one Quaker gunmaker — Samuel Galton — when the pacifist Society of Friends to which he belonged declared his gun-making incompatible with their values. He refused to abandon it, and Satia’s delightful unpicking of the clash between Galton and his critics opens a window on both the centrality of militarism to British life and the emergence of new ideas about guns and their place in civic life.

What remains problematic, however, is Satia’s attempt to relate her rich material to the British industrial revolution. Whenever and wherever it occurs, industrialisation amounts to a total reworking of the way in which societies provide for their people, transforming economic activity, but also social and political life, and the environment. It occurred in Switzerland, for example, only a few decades after Britain, but without guns, violence, and empire. Something else must be at stake.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.