Daniel Ellsberg was courageous and prophetic to the end. Please take a few moments to read and share this interview that he did with the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists during what he knew were his last weeks among us. May they encourage our and others’ actions that lead us to greater peace and humanity’s continued survival.

— Joseph Gerson / Campaign for Peace Disarmament and Common Security

Daniel Ellsberg’s Message to Us,

And to Future Generations

Martin E. Hellman / The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

(June 16, 2023) — Dan Ellsberg was a brave man. In an effort to end the Vietnam War, he risked spending the rest of his life in jail by leaking the Pentagon Papers. In so doing, he changed history—and our knowledge of our own history.

I’ve been privileged to know Dan for almost 40 years, as a friend and as an activist who is trying to save humanity from our self-created nuclear Doomsday Machine. So it was with sadness and a sense of impending loss that I read his March 2 post, where he revealed that he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and had been given less than six months to live.

When the Bulletin invited me to write this piece about Dan, I had a conversation with him so he could tell us what he would like to say to us and to future generations, upon his death. (He died on June 16 at his home in Kensington, Calif., at age 92.)

We met on April 19, and Dan was in good spirits throughout our talk. In fact, as he looked over the list of questions I thought we should address, this one produced a smile and a laugh:

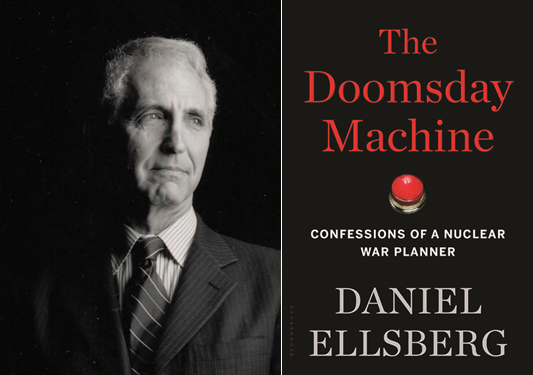

In your book, The Doomsday Machine, you talk about the discrepancy between what Americans are told is the purpose of our nuclear arsenal—preventing aggression—and its actual purpose—“to limit the damage to the United States from Soviet or Russian retaliation to a US first strike against the USSR or Russia.”[1]

I was surprised to find the goal of winning a nuclear war in both the Trump and Biden Nuclear Posture Reviews.[2]

What do you think should be done to bring stated and actual policy in line with one another?

Dan’s laughter was sparked by seeing the goal stated so baldly, especially since both Ronald Reagan and Joe Biden had stated that, “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

Dan then noted that America’s nuclear posture is “directed toward meeting that mission” (that is, winning a nuclear war), even though such a mission is “infeasible and impossible.” He decried the American nuclear establishment for giving “no importance whatever to expressing in public what their actual aims and interests and options are.” He also noted that Russia does roughly the same thing and that this refusal to acknowledge reality has to change.

In The Doomsday Machine, Dan recommends a two-step process to make the world safer (see pages 335-350). First, he notes, current, bloated nuclear arsenals and unrealistic war fighting plans would destroy the planet if used. He then says that:

… you can’t eradicate the knowledge of how to make nuclear weapons and delivery systems. But you can dismantle a Doomsday Machine [that would destroy the planet]. … the existence of one such machine [does not] compel or even create a tangible incentive for a rival or enemy to have one. In fact, having two on alert against each is far more dangerous for each and for the world than if only one existed.

… the current danger of Doomsday could be eliminated without the United States or Russia coming close to total nuclear disarmament, or the abandonment of nuclear deterrence, either unilaterally or mutually (desirable as the latter would be). …

This dismantlement of the Doomsday Machines is not intended as an adequate long-term substitute for more ambitious, necessary goals, including total universal abolition of nuclear weapons. We cannot accept the conclusion that abolition must be ruled out “for the foreseeable future” or put off for generations.

Our subsequent conversation dealt with a variety of aspects of nuclear risk and how to reduce it.

The Pentagon Papers,

Vietnam, and Nuclear Risk

Marty: Let’s talk about Vietnam and The Pentagon Papers. They are what you’re best known for and were the subject of Steven Spielberg’s 2017 movie, The Post. In your March 2 letter telling us of your medical diagnosis, you say:

When I copied the Pentagon Papers in 1969, I had every reason to think I would be spending the rest of my life behind bars. It was a fate I would gladly have accepted if it meant hastening the end of the Vietnam War, unlikely as that seemed (and was). Yet in the end, that action—in ways I could not have foreseen, due to Nixon’s illegal responses—did have an impact on shortening the war. In addition, thanks to Nixon’s crimes, I was spared the imprisonment I expected, and I was able to spend the last fifty years with Patricia and my family, and with you, my friends.[3]

Dan: In the Bulletin, I would prefer to focus on my main concern in life, which is nuclear war.

Marty: But Vietnam did have nuclear risk associated with it, as you know. Conventional war, as in Vietnam, and nuclear war are inextricably interconnected, with the most likely spark for setting off a nuclear war being a conventional conflict that spirals out of control. That almost happened in Cuba in 1962 and could happen today in Ukraine.

Dan: From the very beginning I was aware that nuclear weapons had been discussed as a possibility in Vietnam. The whole basis for my copying The Pentagon Papers was news I got from Mort Halperin, who was working for Henry Kissinger, that Nixon did not mean to get out of Vietnam on any terms that had a realistic chance of being accepted by the North Vietnamese, and thus, that the war would continue and would get larger and would ultimately lead to the use of nuclear weapons.

And yet, most of that time, the public at large and even most of the government had no notion that there was the slightest possibility of the use of nuclear weapons. And that’s what did happen in the offensive of ’72, when Nixon was urging Kissinger actually to consider the use of nuclear weapons. A transcript of formerly secret White House tape recordings shows President Nixon telling Henry Kissinger, “The nuclear bomb, does that bother you? I just want you to think big, Henry, for Christsakes.”[4]

In the 50 years since The Pentagon Papers came out, no one has asked me the question, why did Nixon and Kissinger consider me a dangerous person, let alone—to use Kissinger’s words—the most dangerous man in America?

The answer is because they knew that I knew the threats they were making [including nuclear threats]. They knew those threats had to be kept secret from the American public, even though we were directly making them to the North Vietnamese. And therefore, I was dangerous in that I threatened their national security policy.

So they had to shut me up, and they tried a number of ways to do that, mainly to blackmail me, but also by bringing people up from Miami to incapacitate me. Watergate burglar and CIA operative Bernard “Macho” Barker told Lloyd Shearer of Parade, “My purpose was to break both his legs.”

But I think that was not the main purpose, because that would not have shut me up. I think it had to do with my head and my mouth. Watergate Assistant Special Prosecutor William Merrill had no doubt that their purpose was to kill me. He said that these guys never used the word kill. They used words like incapacitate, neutralize with extreme prejudice, and various things.

Nuclear Weapons Are a Sword of Damocles,

Hanging by the Slenderest of Threads

Marty: Let’s come back to what you would like to say to future generations—or people right now even.

Dan: Right now, that there is, and has been for 70 years, a very significant danger of the end of civilization: the death of most humans on Earth within a year by the effects of nuclear winter and nuclear fallout. And that almost nothing has succeeded in lowering that probability, although there are many things that could be done and should have been done. But perhaps it is not too late to accomplish those things now.

We are living, as John F. Kennedy put it, “under a sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads.” And that thread has not been strengthened in the slightest over the years.

What is happening now in the new Cold War is that the chance of reducing that risk is vanishing, the door is in the process of closing.

Is it already too late? We don’t know. But I choose to act, and I urge others to act as if it’s not too late. And I can be very specific on what that would mean.

We need coordination of action that also applies to climate change. It is hard to imagine a way of reducing the global emissions of CO2 that does not involve coordinated action between the major emitters like the US, China, India, Russia, and Europe.

Coordinated action of a kind that seems almost impossible after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, exploited as that has been by the West to reintroduce a Cold War in which the aims of the adversary are magnified, in which military solutions are looked for. So the chance of lowering the arms budget has virtually disappeared. But, even more importantly, the chance of doing any of the things that would lower the risk of nuclear winter has been almost eliminated at this point.

For over half a century, the existence on both sides of vulnerable land-based ICBMs[5] has been the hair trigger to the Doomsday Machine. They pose a use-it-or-lose-it mentality which encourages each side to launch its missiles on ambiguous warning, lest they be destroyed—in order to attack the ICBMs of the other side. The elimination of just one of these pairs of ICBMs would significantly reduce the chance of all-out nuclear war taking place, even in the event of a small nuclear exchange. So it would be the strongest thing we could do do. The warheads in the submarines are far more than enough, even without any ICBMs.

Along with eliminating the ICBM “use-them-or-lose-them mentality,” policies of no first use would be important changes for both sides. It’s been argued that a no-first-use statement would have no more significance than the statement that threatening a nuclear attack is inadmissible, while you continue to make threats, or the statement that nuclear war is not winnable, while you spend trillions of dollars trying vainly to win it. But a no-first-use statement is necessary as part of a policy of changing this entire stance away from a first strike.

The numbers [of nuclear warheads] per se don’t matter so much, except for reducing them down to a level that could not produce Doomsday, could not produce omnicide. The potential for that catastrophe has existed for decades and can be eliminated without giving up deterrence.

Does any nation have the right to threaten to kill billions of people? I would say they don’t, and they cannot possibly justify it by a need to deter nuclear attack on themselves, since much smaller arsenals would serve that purpose.

But it gets very tricky when you add that little thing of deterring a nuclear attack against your allies. That produces a very strong incentive to make it look as though you believe you could lower the damage to your own nation, and God knows we have acted as though we believe that hoax since the ’50s or ’60s.

When it comes to that, it’s a total license, as McNamara found, to build a first-strike weapon, to try and make it credible that you’ll respond to an attack on your ally by initiating nuclear war against a nuclear weapon state. And there’s no limit to what you can spend under that crazy assumption.

In other words, it’s been a madman threat from the very beginning. Nixon, who tried to convince the Soviets and the North Vietnamese that he was crazy[6] in an effort to end the Vietnam War on his terms, said he was imitating Eisenhower, which is true. The same is basically true of Truman in the 1948 Berlin crisis. It’s been true all along that it was mad, but it turns out, it’s a madness that is very easy to make credible. Humans are that mad.

How do you move people from a totally insane plan to which they’re committed? It’s like waking up somebody who’s sleepwalking—a dangerous process. You may cause panic. Or they’re walking on a precipice; how do you move them away from it? Or they’re drunk, how do you deal with it? You don’t just tell them that it’s wrong; You somehow have to coax them away from this insane path that they’re on. How do you persuade them away from a plan that is batshit crazy?

The Risk of a Nuclear War

Marty: We have both been concerned with evaluating the risk of nuclear war. That risk may be small per year, but builds up over time, just like one mile an hour is not very fast, but if you go one mile an hour for a whole year, you’ll cover almost 9,000 miles.

Dan: Look, the risk of a nuclear war on October 27th, 1962 during the Cuban crisis—known as “Black Saturday”—was much more than even; 90 percent or something like that.[7] The prominent Cold War strategist Paul Nitze thought there was at least a 10 percent chance of something going wrong and blowing up the world. McNamara thought that there was a high chance he would never see another Saturday night.

My guess is that there is not a high likelihood of nuclear war in the current stalemate in Ukraine, so long as Putin is not confronted with losing Crimea or all of the Donbas. But if American troops or Polish troops or German troops were to maintain those tanks and planes that are being given to Ukraine by the West, or to man them, that would be a very significant change, because it could confront Russia with actually losing the Donbas or Crimea. And I think, in those circumstances, Putin would be strongly tempted, as we would be in similar circumstances, to break through that with “small” nuclear weapons in an effort to bring people to their senses and say, “This can’t go on. You’ve got to negotiate at our terms.” Putin’s use of nuclear weapons in that kind of scenario could succeed, but probably would not.

And another thing that I’ve learned, Marty, and that I think is not sufficiently appreciated, is that men in power are willing to risk world annihilation rather than to accept a short-term loss. And it’s not a question of realism or unrealism, it’s a willingness to gamble. They know it’s not likely to succeed, but that doesn’t mean they won’t do it, because there is a chance that it may succeed, which is enough to get them to gamble the world.

Our presidents have that power every hour of every day.

Dan’s Father’s Awakening

Dan: Well, Marty, the first time I ever heard your name was in an article that you published in 1985. I can tell you exactly when it was because my father died in 1985, he was 96, and he was in the same situation I am at the moment. We didn’t know then, but he did die a week after I had this conversation with him. You and I are having this conversation a month or two or so, three, six, probably a month before I’m gone.

It so happens that in that week before he died, he had read your article in a journal that he trusted, the journal of Tau Beta Pi, the engineering honor society, to which he belonged as a structural engineer. And he took seriously what he read there.

In that article, you said that there was a mathematical certainty of eventually destroying life on Earth if we did not change in fundamental ways.

Marty: Right. The title of the paper was “On the Inevitability and Prevention of Nuclear War.” How we could avoid that, but the inevitability on our then-current path and, unfortunately, our now-current path.

Dan: So years after The Pentagon Papers, which was ’71, this was in 1985, he had never taken too seriously all my talk about nuclear war; wasn’t his subject, wasn’t his field particularly, he didn’t get too interested in it. He did follow me on Vietnam, and I convinced him, I persuaded him that that war should be ended. So in that respect we’d come together. So he said in this particular last talk together that it’s wrong to be doing something which has, the way he put it, using your term, a mathematical probability, eventually approaching one, of blowing up the world, ending living life on Earth—a Doomsday machine, without using that term. And he said it’s wrong to have that capability or for it to exist.

And I said, “Dad, there are those who would say that it makes it less likely to have the overall cataclysm if you have the ability to blow things up; that will make it less likely that it will ever go off at all.”

And he said something very interesting to me that I haven’t seen reproduced; it gave me something to think about, which I’ve never fully finished thinking about to this day. He said, “Yes, but there is a moral cost to having this capability at all. It’s not just a matter of a risk and a cost of blowing the world up. There is a moral cost in telling yourself and teaching your children that there are circumstances that would justify killing everything and therefore that would justify having this capability.”

I would say, from a reasonable ethics, there is no such objective. The objectives of national policy and imperial policy are the same as they’ve always been, except now we have the capability of pursuing them by means of massacring everybody. And every nation has proven absolutely willing to do that and wanting to do that, and the ones who don’t do it themselves are quite willing to be allied with ones who do.

The Need for Action: A Fool’s Errand?

Dan: People just don’t realize how big this is. What do they do? They don’t do anything one way or the other. The death of humanity is not something that moves them to vote. They act as if there is no chance to make any difference. As if it’s impossible to change things.

Yet, we all thought the Berlin Wall coming down was impossible. Nelson Mandela becoming president of South Africa without a violent revolution seemed impossible.

In the same way, I currently cannot see any chance of getting rid of ICBMs, or of no-first-use. But miracles do happen. I choose to act as if it makes a difference. And it’s just a choice. I can’t defend that. It’s just a better way to live. It’s the way I choose to live. We can work to prevent the cataclysm.

And I think one aspect of that is, 12 months into this Ukraine war, suggesting anything that involves a chance to end it is seen as being on the wrong side. Yet going on as we have has risks vastly disproportionate to any advantage that would be gained in another 12 months of stalemate. The latest leaks indicate exactly what The Pentagon Papers showed: that the people inside perceive themselves as in a stalemate for at least the next 12 months. So what will the effort to break through the stalemate in the 12 months be likely to accomplish? Very little. And what’s the possible downside? The end of everything, essentially.

And likewise, on Taiwan. It’s outrageous. We are risking everything over the issue of the control of Taiwan. When I say risking everything, I mean we are risking all-out nuclear war. And would people, a thousand years ago, have taken such a risk? I think if they could have, they would have. So we’re not worse than people were. We just have a lot more at stake. This is not a species to be trusted with nuclear weapons.

Concluding the Interview

Marty: In your email to me, you said, “Other than dying, I’m okay.” I like your humor.

Dan: Well, we’re all dying. I’m in very good shape. For my best friends, I would not wish better than to have the last month I’m having with my wife and my friends like you.

Editor’s note: A 2018 Bulletin interview with Daniel Ellsberg about his book, The Doomsday Machine, can be found here.

Notes

[1] From Ellsberg’s book, The Doomsday Machine, page 12. All page numbers refer to the hardcover edition of The Doomsday Machine.

[2] Biden’s NPR says, “the Joint Force will need to be postured with military capabilities—including nuclear weapons—that can deter and defeat other actors who may … engage in opportunistic aggression.” Trump’s NPR says, “No country should doubt the strength of our extended deterrence commitments or the strength of US and allied capabilities to deter, and if necessary defeat, any potential adversary’s nuclear or non-nuclear aggression.”

[3] Nixon’s “plumbers” were apprehended when they burglarized the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate building on June 17, 1972, leading to the Watergate scandal that caused Nixon’s resignation. But almost a year earlier, on September 3, 1971, they broke into Dan’s psychiatrist’s office in an operation that had been approved by John Ehrlichman, one of Nixon’s top aides, on the condition that it not be traceable. Fortunately for Dan, the break-in was traced to the plumbers and, when the judge in his trial learned of this government misconduct, he dismissed all charges.

[4] The Doomsday Machine, page 309.

[5] Intercontinental ballistic missiles.

[6] Dan is referring to Nixon’s “madman theory.” Nixon’s chief of staff H.R. Haldeman says that Nixon told him: “I call it the Madman Theory, Bob. I want the North Vietnamese to believe that I’ve reached the point that I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to

them that ‘for God’s sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about Communism. We can’t

restrain him when he is angry—and he has his hand on the nuclear button’—and Ho

Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace. Source: H.R. Haldeman with Joseph DiMona, The Ends of Power, New York, Times Books, 1978, p. 83. Emphasis is in the original.

[7] Dan has information that was unavailable to any American at the time. It wasn’t until 1992 that we learned the Soviets had battlefield nuclear weapons on Cuba to repel the kind of American invasion that the US military wanted to mount. And it was only in 2002 that we learned that three Soviet submarines that were attacked by American destroyers each carried a nuclear torpedo. According to an account by a crew member, the captain of one of those submarines gave orders to arm the nuclear torpedo but was talked down.