‘Everyone Should Be Concerned’

Graham Readfearn / The Guardian

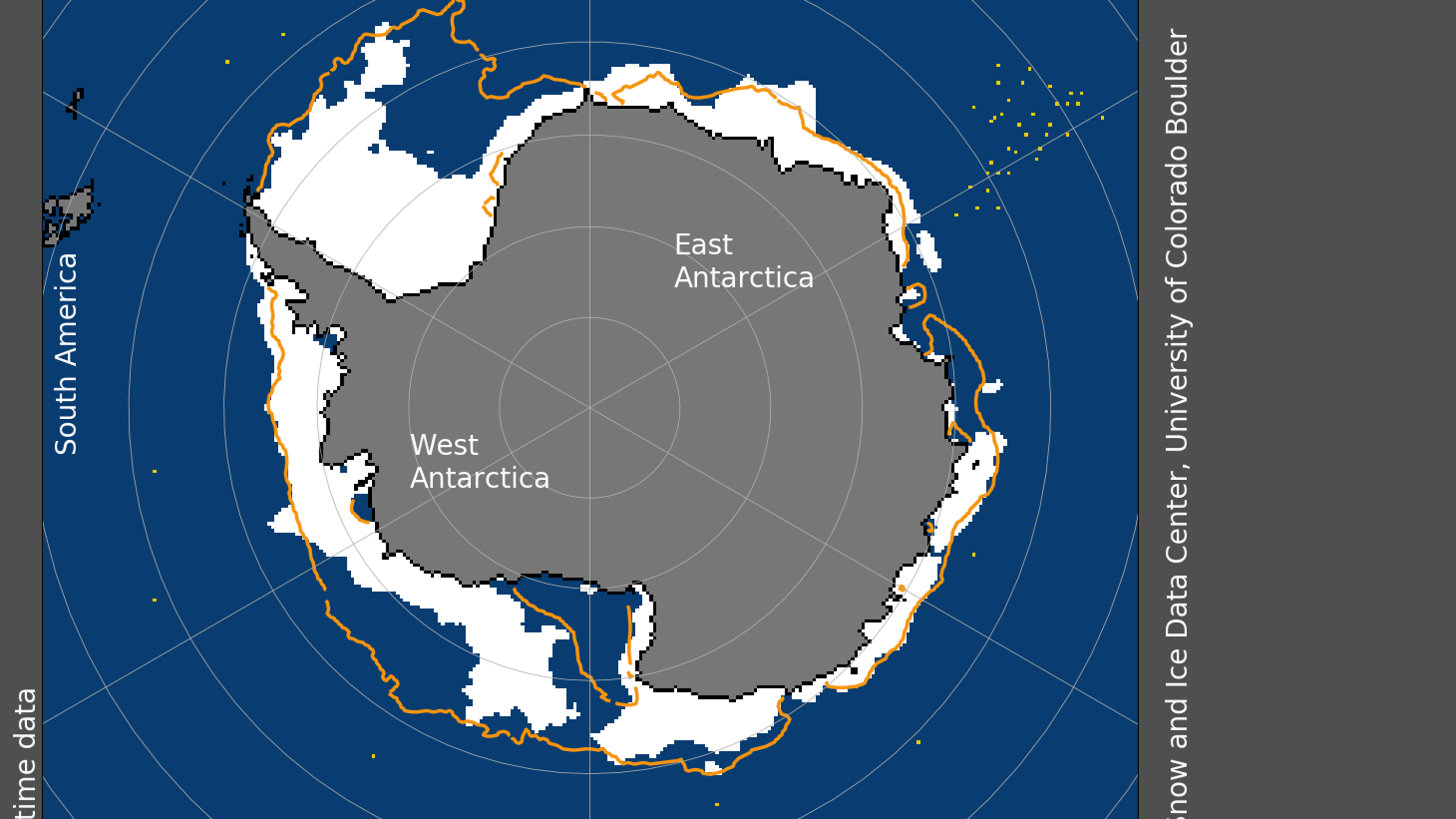

(March 4, 2023) — For 44 years, satellites have helped scientists track how much ice is floating on the ocean around Antarctica’s 18,000km coastline.

The continent’s fringing waters witness a massive shift each year, with sea ice peaking at about 18m sq km each September before dropping to just above 2m sq km by February.

But across those four decades of satellite observations, there has never been less ice around the continent than there was last week.

“By the end of January we could tell it was only a matter of time. It wasn’t even a close run thing,” says Dr Will Hobbs, an Antarctic sea ice expert at the University of Tasmania with the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership.

“We are seeing less ice everywhere. It’s a circumpolar event.”

In the southern hemisphere summer of 2022, the amount of sea ice dropped to 1.92m sq km on 25 February — an all-time low based on satellite observations that started in 1979.

But by 12 February this year, the 2022 record had already been broken. The ice kept melting, reaching a new record low of 1.79m sq km on 25 February and beating the previous record by 136,000 sq km — an area double the size of Tasmania.

In the southern hemisphere’s spring, strong winds over western Antarctica buffeted the ice. At the same time, Hobbs says large areas in the west of the continent had barely recovered from the previous year’s losses.

“Because sea ice is so reflective, it’s hard to melt from sunlight. But if you get open water behind it, that can melt the ice from underneath,” says Hobbs.

Hobbs and other scientists said the new record — the third time it’s been broken in six years — has started a scramble for answers among polar scientists.

The fate of Antarctica — especially the ice on land — is important because the continent holds enough ice to raise sea levels by many metres if it was to melt.

While melting sea ice does not directly raise sea levels because it is already floating on water, several scientists told the Guardian of knock-on effects that can.

Sea ice helps to buffer the effect of storms on ice attached to the coast. If it starts to disappear for longer, the increased wave action can weaken those floating ice shelves that themselves stabilise the massive ice sheets and glaciers behind them on the land.

Soaring solar temps melted 20% of continent’s ice in a few daysl

One major area of concern is a marked loss of ice around the Amundsen and Bellinghausen seas on the continent’s west.

Even as the average amount of sea ice around the continent grew up to 2014, these two neighbouring seas saw losses.

That’s important because the region is home to the vulnerable Thwaites glacier — known as the “doomsday glacier” because it holds enough water to raise sea levels by half a metre.

“We don’t want to lose sea ice where there are these vulnerable ice shelves and, behind them, the ice sheets,” Prof Matt England, an oceanographer and climate scientist at the University of New South Wales, says.

“We are probably starting to see signs of significant warming and retreat of sea ice [in Antarctica]. To see it getting to these levels is definitely a concern because we have these potentially amplifying feedbacks.”

Data provided by scientists Dr Rob Massom, of the Australian Antarctic Division, and Dr Phil Reid, of the Bureau of Meteorology, shows two-thirds of the continent’s coastline was exposed to open water last month — well above the long-term average of about 50%.

“It’s not just the extent of the ice, but also the duration of the coverage,” Massom says. “If the sea ice is removed, you expose floating ice margins to waves that can flex them and increase the probability of those ice shelves calving. That then allows more grounded ice into the ocean.”

Massom and Reid published a study last year that found that, since 1979, the Amundsen Sea region was seeing longer periods without ice and more of the coastline was being exposed to open ocean conditions.

Dr Ted Scambos is a sea ice expert at the University of Colorado Boulder who also works on Antarctic sea ice at the university’s National Snow and Ice Data Center — a world centre for monitoring ice at the poles.

He said the downturn in sea ice in Antarctica “is causing the scientific community to wonder if there’s a process that’s related to global climate change”.

Antarctica is hard to study not just because of its remoteness, but in the challenges of gathering data around a continent exposed to huge variations in wind and storms from all sides.

Scambos said: “Since 2016 there has been a fairly sharp downturn [in sea ice] and especially with these back-to-back record years as well as many months being at near record lows, it’s causing the scientific community to wonder if there’s a process related to global climate change.”

He said while the most recent record could be related partly to a La Nina climate system that tends to deliver warmer winds to the continent’s peninsular, that didn’t explain the losses in other areas.

“We’re still trying to get to grips with what’s different now,” he says. “But it’s clear that reduced sea ice will have an impact. It’s going to have an impact on the continental ice because so much of the coast will be exposed.”

For many years Antarctica had seemingly been confounding some climate models as sea ice had — on average — slightly increased until a crash in 2016.

Dr Ariaan Purich, a climate scientist at Monash University, looked at why the sea ice didn’t behave as some expected.

She said it was likely caused by changing winds and, counterintuitively, meltwater from the land entering the ocean that made it easier for ice to form.

One study suggested that a warming ocean had also contributed to the sudden 2016 drop in sea ice.

“All the models project that as the climate warms, we expect to see [Antarctic sea ice] decline,” she says. “There’s widespread consensus on that. So this low sea ice is consistent with what the climate models show.”

Antarctic scientists are now scrambling to work out what’s happening. Are the drops in sea ice and the back-to-back record lows just a natural phenomenon in a continent notoriously difficult to study? Or are these records another clear sign the climate crisis is beating down on the frozen continent?

“Antarctica might seem remote but changes around there can affect the global climate and the melting ice sheets affect coastal communities around the world,” says Purich.

“Everyone should be concerned about what’s happening in Antarctica.”

From the Guardian: I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I was hoping you would consider taking the step of supporting the Guardian’s journalism.

From Elon Musk to Rupert Murdoch, a small number of billionaire owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world. The Guardian is different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest — not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much US media — the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. While fairness guides everything we do, we know there is a right and a wrong position in the fight against racism and for reproductive justice. When we report on issues like the climate crisis, we’re not afraid to name who is responsible. And as a global news organization, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective on US politics — one so often missing from the insular American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone — whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.