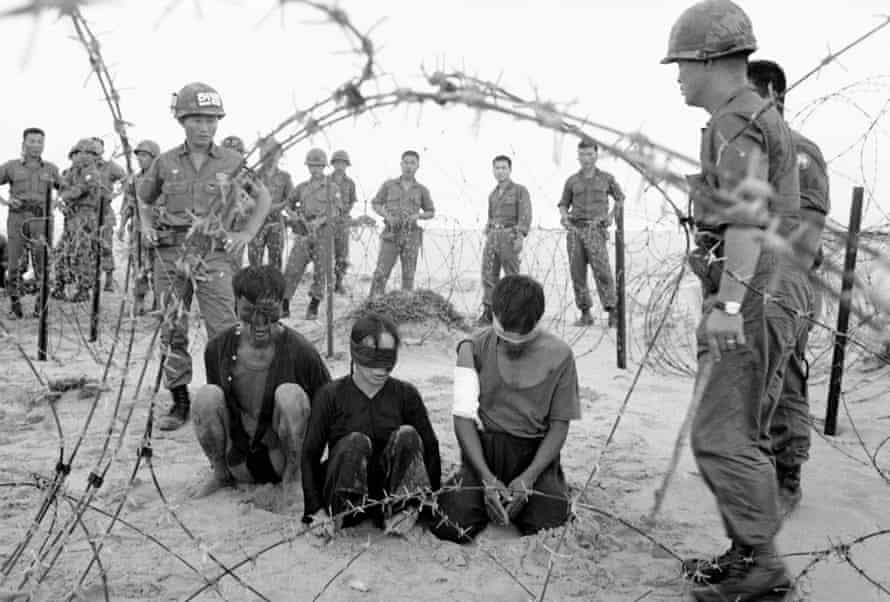

Vietnamese villagers about to be murdered by US troops in 1968.

The Biggest Vietnam War Story

That Americans Don’t Talk About

John Summers / The Boston Globe

(August 11, 2023) — One day after my mother informed my father of her pregnancy with me, he received orders from the US Marine Corps to report to Vietnam. One month later, he was patrolling Quảng Nam Province with a brigade of South Korean Marines nicknamed the “Blue Dragons.” I’ve long yearned to piece together a story of how the faraway events coinciding with my gestation shattered our family after his return.

The war’s brutality has never been anybody’s secret. By now, the 50th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords, no aspect of any feature of the conflict would seem to remain unexplored. Yet my boyhood quest to mine the details of what my father did in Vietnam has foundered over the first and most general question: What were South Korean Marines doing there?

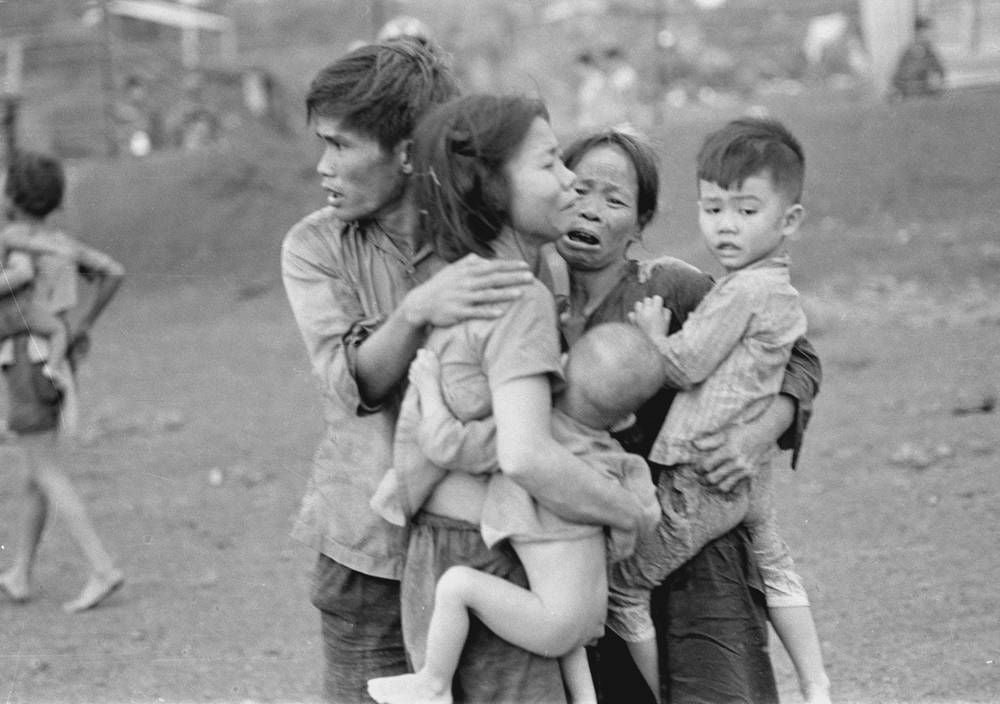

Nguyen Thi Thanh, a survivor of a massacre carried out by South Korean troops who fought alongside Americans, pointed out the names of relatives at a memorial in the Quang Nam Province of Vietnam in 2021.LINH PHAM/NY

A clue tapped me on the shoulder earlier this year. In February, a district court in Seoul ordered the government of South Korea to pay compensatory damages to Nguyễn Thi Thanh, a Vietnamese woman, in a lawsuit she brought over an event that had taken place 55 years earlier, nearly to the day.

On the morning of Feb. 12, 1968, about 100 combat troops from the Republic of Korea’s 2nd Marine Brigade poured into Phong Nhị in Quảng Nam Province. The Blue Dragons set homes ablaze and then proceeded to shoot, stab, drown, and hack to death 70 women, children, and infants. The butchery left no uninjured survivors. Nguyễn, 8 years old, took a bullet to the stomach. The rest of her family perished.

The South Korean government has appealed the verdict, which marked the first time any court in South Korea had attributed culpability for a massacre of Vietnamese civilians. More such lawsuits are likely to be brought. Since 1999, journalists, scholars, and veterans in Seoul have documented more than 80 similar massacres of a total of (at least) 9,000 civilians in three provinces. “There’s a strong sense among the survivors that the problem has to be resolved before their generation passes on,” Ku Su-jeong of the Korean-Vietnamese Peace Foundation said in 2016.

Only a few US news outlets reported Nguyễn’s victory. The silence bespeaks a curious subtraction of memory.

Between 1965 and 1972, South Korea contributed 325,517 combatants at our behest. (Australia’s 60,000 rated the next highest contribution by an American ally. Some 2.7 million Americans served.) South Korean belligerents formed the largest phalanx of foreign fighters in Vietnam other than ours, and they even outnumbered ours in the final two years. Most Americans today, however, have forgotten the little our predecessors learned about this feature of the conflict at the time. Of tens of thousands of books in English about the Vietnam War, not one is dedicated to South Korea’s participation.

The Vietnam commitment marked the first time in Korea’s 4,000-year history that its fighters left the peninsula to wage war. The American and South Korean governments conspired to make it appear as if these deployments answered a call that came directly from South Vietnam. But in 1970 a US Senate committee detailed a mercenary motive in 2,000 pages of documents appended to its report of hearings into the matter.

Our government footed the entire cost of the South Koreans’ ammunition, aircraft, and weapons, trained and quartered their officers, built barracks for their infantry, and paid bonuses at a rate 23 times as high as their base pay for the duration of the war.

South Korea is finally being held to account for the carnage its mercenary troops inflicted on Vietnamese civilians. But no one seems to be reckoning with US complicity in the atrocities.

A document called the Brown Memorandum — named for Winthrop G. Brown, the US ambassador to the Republic of Korea — codified the terms of a business transaction. In addition to paying for war materiel and troop bonuses and providing security guarantees against North Korea, our government agreed to purchase all goods and services for the South Korean forces exclusively from South Korean businesses.

The windfall, totaling more than $1 billion, rapidly modernized the country’s heavy industry. Our money contributed 4 percent of South Korea’s gross domestic product and 20 percent of its foreign exchange earnings. President Park Chung Hee, having seized power in a 1961 coup d’état, fortified authoritarian rule in the bargain.

In March 1973, our aircraft removed the last of the South Korean troops to a home country rejuvenated by war profiteering. With its end, President Park turned to formal dictatorship. Western economists have been calling the transformation of South Korea a “miracle” ever since.

A memorial to villagers of the Mi Lai massacre.

Shuffled Off Stage

The South Koreans based their detachment in the Central Highlands, a region thick with enemy forces. The Tiger and the White Horse divisions secured the coast and disrupted supply lines. The Blue Dragon Marine brigade conducted search-and-destroy missions in villages and hamlets. American liaisons such as my father escorted the brigade in the countryside, coordinating helicopter and gunship support and radioing for napalm strikes.

“They rank with the best fighters in Vietnam,” General William Westmoreland told a joint meeting of the US Congress in 1967. In a war of attrition, their “kill ratio” of 10 enemies for every loss of one of their men was touted as evidence of their proficiency.

Westmoreland described the Blue Dragon contingent as “a troubleshooting outfit.” Some of the trouble they shot had been herded into refugee camps. Survivors reported members of the brigade baiting children into groups with candy and cake and then turning machine guns and grenade launchers against them. Other survivors alleged the Blue Dragons beheaded five children in 1966 and deposited their skulls on a highway as a warning to insurgents.

American newspapers celebrated the florid cruelty of our mercenaries. “Korean Marines are Legends,” crowed the Copley News Service on Nov. 11, 1966, describing them as “larger-than-life figures with dusky yellow skins, high cheekbones, and almond-shaped eyes.”

The dispatch quoted US field commanders praising their exemplary methods of terror: “After every fight they skin a few of the dead and leave them behind or cut off their ears and put up their heads on bamboo poles.” A Scripps-Howard report endorsed the logic of their bloodletting: “Their rough tactics discourage the Viet Cong from attacking them. When Koreans receive fire from a village, they are likely to level it and spread word that the same thing will happen to the next village from which they receive harassment.”

As discipline and morale in our forces wobbled, the South Korean Marines stood firm. The news service UPI extolled them as “one of the toughest fighting units left in Vietnam” in 1971. Their unsentimental ferocity chiseled proof of concept into America’s military strategy. “The ROK Marine pacification program is considered a success,” UPI wrote, “and the corps has gotten over an ugly incident at Barrier Island near Da Nang in which it was reported that many civilians were massacred during a clearing operation.”

The next month, as the Blue Dragons began to draw down, their commander, Brigadier General Hur Hong, assured the Los Angeles Times his men’s thirst for blood wasn’t slaked: “Now we would like to go back to Korea and cut off the head of Kim Il Sung.”

This May, as the verdict in Nguyễn Thi Thanh’s lawsuit roiled Seoul, South Korean veterans attended a Vietnam War commemoration ceremony in Washington, D.C. Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro thanked them for their service. To the bare fact of that service, all the most comprehensive and acclaimed histories of the war have given a few grudging sentences, if any.

The latest doorstop, Carolyn Woods Eisenberg’s “Fire and Rain,” appeared this year with an “avalanche of material” declassified in recent decades. Eisenberg omits South Korea entirely. Journalists, novelists, and filmmakers have perpetuated the erasure. The Library of America’s 1,600-page anthology “Reporting Vietnam” affords the subject fewer than 10 words. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s documentary “The Vietnam War” runs 18 hours and features interviews with nearly 100 veterans “from all sides.” No South Koreans appear.

Our commentators still tend to interpret the “loss” of Vietnam as a “tragedy,” a fateful concatenation of domestic politics, diplomacy, and military strategy. A rote recitation of the My Lai massacre of 1968 often stands in for the unmentionable fact of many more atrocities committed by US troops. (In 1969, the Pentagon’s Vietnam War Crimes Working Group substantiated 320 massacres and documented another 500 or so allegations.)South Korea’s have been shuffled off stage along with the rest, so that they don’t disturb the dignified musings of tragedy.

The silence deprives us of a framework for the necessary question: What responsibility do we bear for atrocities committed by South Koreans in our Vietnam War? The US Army’s Inspector General found “some probability that a war crime was committed” by them in Phong Nhị on Feb. 12, 1968, the subject of the court ruling in Seoul this year.

“After a limited investigation,” General Westmoreland averred to Lieutenant General Chae Myung-shin, commander of South Korea’s forces in Vietnam, “it was recognized that this matter is more properly a concern of your country, as a signatory to the Geneva Conventions, and our investigation was terminated.” To my knowledge, nobody in a position to do so has ever undertaken a legal or moral inventory of our use of mercenaries in the war.

How not to “win hearts and minds.”

What my 21-year-old father saw and did with the Blue Dragons he divulged just once, in a private conversation with my mother over my crib. The marriage didn’t last much longer. To his final breath, however, he declined to discuss with me what turned out to be the most important event for both our lives.

Maybe he could never find the words to express the meaning of his complicity in extreme violence. Or maybe he feared I would pity him as a victim of circumstance, denying him moral agency. Either way, the wedge of conscience that separated us never lifted — and cheated us both.

In “Un-nameable Objects, Unspeakable Crimes,” James Baldwin wrote that “the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.” Some stories never end. Others never begin.

John Summers is the editorial director of Lingua Franca Media. His edited collection of Dwight Macdonald’s writings on art, politics, and atrocity will appear next year from the University of Chicago Press.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.