The 1953 Coup that Eventually

Blew Back Badly on the US

Al Ronzoni / Substack

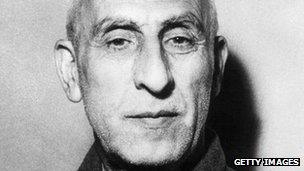

Mohammed Mossadegh (1882-1967), a Western educated, secular democratic reformer, appointed prime minister of Iran in 1951 after a landslide vote of support in the Iranian Parliament. After nationalizing the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. (the predecessor of BP), he was removed from power by a joint British-American engineered coup in 1953.

(September 4, 2023) — One of the big events of my youth was the Iran Hostage Crisis. I remember sharing the feelings of millions of Americans: “How dare these crazy, hate-filled people take our diplomats hostage!” “Fuck Iran!” It was probably the greatest humiliation we’ve ever experienced as a nation.

Compounding the psychological torment was ABC’s nightly news coverage of America Held Hostage (the brainchild of Roone Arledge, who felt it was the best way to compete against NBC’s Tonight Show), where we would all collectively stew about the apparent impotence of our government and military to do anything about the hostage crisis. America Held Hostage later morphed into the long running Nightline program and launched the career of Ted Koppel as a national TV news personality.

When President Jimmy Carter finally decided to take action to rescue the hostages, one of the helicopters involved crashed into a transport aircraft, killing eight American servicemen, one Iranian civilian and the mission was aborted.

America seemed to have become the “pitiful, helpless giant” described by President Richard Nixon in an address to the nation ten years earlier. But in the aftermath of the failure of “Operation Eagle Claw,” the Iranians began negotiations with the US for the hostages’ release. Carter worked tirelessly on this effort up until the final moments of of his presidency but it was Ronald Reagan who reaped the political reward when they were finally released just minutes after he had been sworn into office.

Most Americans, then and now, probably know little or nothing about Iran’s millennia-old history and unique culture. Nor would they likely know anything about its more recent history and how that related to why the hostages were taken in 1979.

After Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi was overthrown in the Iranian Revolution of 1978-79, the Carter administration reluctantly permitted him to enter the US for medical treatment for lymphoma. The State Department had discouraged this decision, concerned about the possible political fallout but Carter bowed to pressure from former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Council on Foreign Relations Chairman David Rockefeller.

The Shah’s admission to the United States intensified Iranian revolutionaries’ anti-Americanism, which had been spawned by years of US support for his brutal, repressive regime. And it also fueled fears that the US might engineer another coup to restore the Shah to power, as it had done in 1953.

Mohammed Mossadegh was born on May 19, 1882. His mother was a princess of the Qajar royal family (1789-1925) and his father was of the distinguished Ashtiani clan, who had served for more than twenty years as Nasir al-din Shah’s (1848-1896) finance minister. By sixteen, Mossadegh was named to his first government post, chief tax auditor for Khorasan, his home province. By all accounts he performed brilliantly.

During Iran’s Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1911, Mossadegh won a seat in the first Majlis (Parliament) though he was still too young to take it. When the reactionary Mohammad Ali Shah (1872-1925) bombarded the Majlis in 1908 with Russian and British support, ultimately leading to the derailment of the revolution, Mossadegh left Iran to study in France and later in Switzerland, where he became the first Iranian to win a European law degree.

Mossadegh was again elected to the Majlis in 1923 but then retired from politics, due to disagreements with the new Pahlavi Dynasty. In 1944, he was once again elected to parliament, this time as leader of Jebhe Melli (National Front of Iran), an organization he helped to found aiming to establish democracy and end the foreign presence in Iranian politics, especially by nationalizing the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.

The company had grown out of an oil exploration concession granted to British financier William D’Arcy by the feckless Mozaffar al-Din Shah in 1901. D’Arcy assumed exclusive rights to prospect for oil for 60 years in a vast tract of territory including most of Iran with the shah receiving a one-time payment of 22,000 pounds (about 2.3 million today, enough to fund his lavish lifestyle), plus a promise of 16% of future profits. But D’Arcy had great difficulty finding oil and was forced to sell most of his rights to a Glasgow-based syndicate, the Burmah Oil Company.

Just as Burmah and D’Arcy were about to give up, geologist George Bernard Reynolds tapped into perhaps the greatest oil field ever found. As Stephen Kinzer notes in his essential book on the 1953 coup, All the Shah’s Men, it didn’t take the British government long to grasp the scope and implications of the find.

It Wasn’t About Communism: It Was About Oil

In 1908, it arranged for a group of investors to form a new corporation, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, to absorb the D’Arcy concession and take control of oil exploration and development in Iran. In 1914, just in time for World War I, the British government purchased 51% of the company, effectively nationalizing the company for Great Britain.

Conditions for Iranian oil workers were abysmal and as the company’s profits soared, Iran’s 16% royalty became ever more questionable. Reza Shah (1878-1944), a military officer who deposed the Qajaris in 1925, establishing his own Pahlavi dynasty, was a nationalist in the mold of Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and sought a more equitable accord with the British. For years they brushed off his demands until, in a fit of anger in 1932, he canceled the D’Arcy concession. This brought them to the table quickly and a new agreement was reached in 1933, whereby the D’Arcy concession was reduced by three-quarters and Iran was guaranteed payments of at least 975,000 pounds annually.

The British also promised to improve pay and working conditions for Iranian laborers, as well as to build schools, hospitals, roads and to provide a telephone system. In return, Reza Shah renewed the concession for another thirty-two years. Disliking the term “Persia,” which had been bestowed on Iran by the West (beginning with the ancient Greeks), he also insisted that the company be renamed the “Anglo-Iranian Oil Co.”

But the issue of the distribution of oil company profits continued to rankle the Iranian people.

As Kinzer notes, in 1947, it reported an after-tax profit of 40 million pounds, while giving Iran just 7 million. And to make matters worse, the British totally reneged on their promise to use some of their profits to improve conditions for Iranian workers. This led to a mass movement to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. for Iran. Even a number of Islamic mullahs, led by Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani were for nationalization. But it was Mossadegh who became the most prominent leader of this movement.

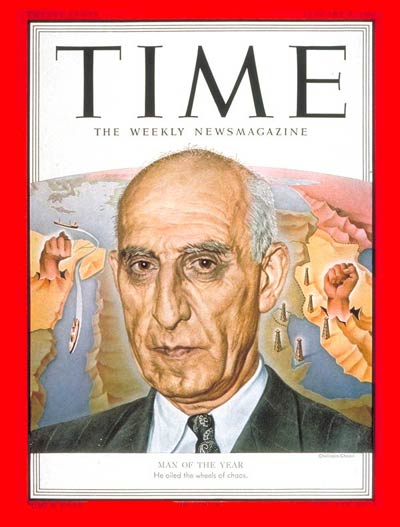

When the Majlis cast its historic vote to nationalize the company on March 15, 1951, Mossadegh became, in the words of Kinzer, “a hero of epic proportions, unable to even step onto the streets without being mobbed by admirers.” Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Reza Shah’s son and successor, has no choice but to appoint Mossadegh prime minister on April 28, 1951. He also became a hero to people all over the Middle East and North Africa, especially those still chafing under European imperialism. Time Magazine even felt compelled to choose Mossadegh as 1951’s Man of the Year, even though the distinction was accompanied by an article that called him “The New Menace,” who had “oiled the wheels of chaos.”

As Kinzer notes, British agents began conspiring to overthrow Mossadegh from the moment the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. had been nationalized. They appealed to US President Harry Truman for help but he had nothing but contempt for the old-style imperialists like the British arguing that “their property” had been unfairly confiscated.

That was certainly not enough of a reason for the US to get involved in overthrowing a democratically elected and popular foreign leader. When Eisenhower assumed office in 1952, the British realized they’d have to take a different tack. Incoming Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother Allan — the incoming CIA director — were more than receptive to Britain’s new horror story: that Iran had immense oil wealth, a long border with the Soviet Union an active Communist Party, known as Tudeh (“Party of the Masses of Iran”) and a nationalist prime minister.

The Dulles brothers bought it hook, line and sinker. They were terrified that Iran might become a “second China” and approved CIA involvement in a coup to remove Mossadegh.

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes