The World Needs an Armistice Day

David Swanson / World BEYOND War

Remarks at Veterans For Peace event in Iowa

(November 11, 2023) — Ukraine needs an armistice.

Palestine needs an armistice.

Nagorno-Karabakh needs an armistice.

Syria, Sudan, Nigeria, and so many countries need an armistice.

The U.S. public and its mass shooters need an armistice.

And by armistice I do not mean a pause to re-load. I mean an end to the idiotic madness of mass-murder that risks nuclear apocalypse, an end in order to negotiate a wiser path, a compromise without further killing.

And by negotiate, I do not mean: You shut up and grovel and do everything I demand or I’ll start the murder machine back up. By negotiate I mean: How can we find a solution that respects everyone’s concerns and allows us to move toward the day we can put this conflict behind us? Negotiating is the opposite of easy. It’s much easier to blow stuff up.

The world’s weapons dealer, the arsenal of dictatorships and so-called democracies alike, can move wars toward armistice and negotiation very powerfully, by halting the flow of weapons.

You wouldn’t hand a mass shooter more bullets while asking him to stop shooting.

Nor should our demands of the U.S. government be limited to imploring it to speak in favor of a ceasefire while shipping over more mountains of free weaponry paid for by you and me, the proud, overly proud residents of the one wealthy nation that can’t do healthcare or education or retirement or infrastructure because it only cares about war.

We need a global armistice.

And we need more than that.

We need a society in which it is acceptable to say that, in which saying that doesn’t make you a treasonous servant of various enemies.

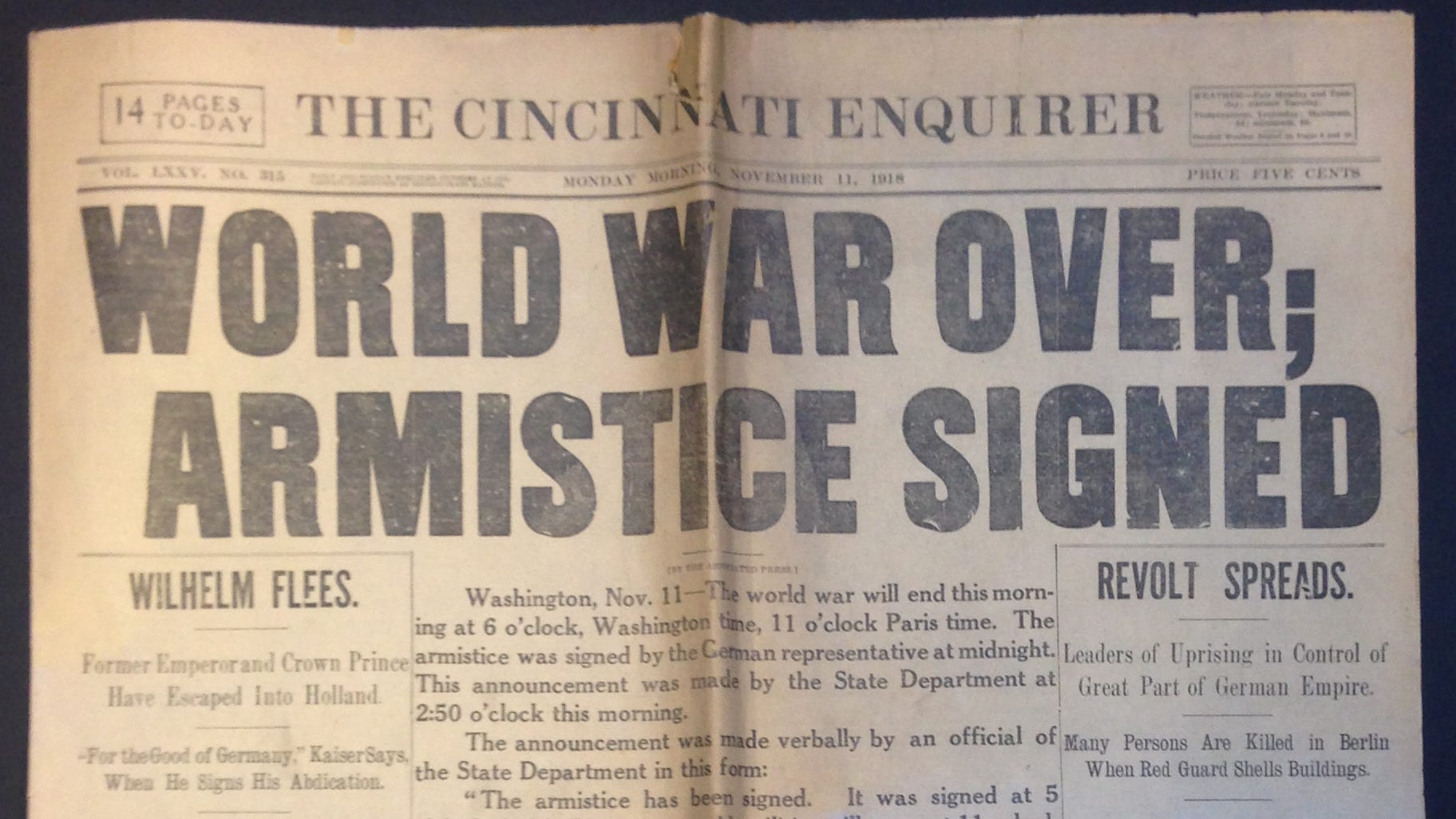

1918 Armistice brings an end to World War I.

We need the sort of society that celebrates Armistice Day as it was created, not as it was transformed into Veterans Day. Armistice Day was a day of ending a war and hoping to end all war making, of imagining that the world had now seen something so awful that it would not allow it to be repeated, of supposing that the peace that would be negotiated at Versailles would not be horribly mangled into effectively a guarantee of World War II. Armistice Day was a day of committing to work for an end to all war.

Exactly at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, in 1918, people across Europe suddenly stopped shooting guns at each other — at least in Europe; they continued for weeks in Africa. Up until that moment, they were killing and taking bullets, falling and screaming, moaning and dying, from bullets and from poison gas. And then they stopped, at 11:00 in the morning. They stopped, on schedule. It wasn’t that they’d gotten tired or come to their senses. Both before and after 11 o’clock they were simply following orders. The Armistice agreement that ended World War I had set 11 o’clock as quitting time, a decision that allowed 11,000 more men to be killed, injured, or missing — we might add “for no reason,” except that it would imply the rest of the war was for some reason.

That hour in subsequent years, that moment of an ending of a war that was supposed to end all war, that moment that had kicked off a worldwide celebration of joy and of the restoration of some semblance of sanity, became a time of silence, of bell ringing, of remembering, and of dedicating oneself to actually ending all war. That was what Armistice Day was. It was not a celebration of war or of those who participate in war, but of the moment a war had ended — and a remembrance and mourning of those war has destroyed.

Congress passed an Armistice Day resolution in 1926 calling for “exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding … inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.” Later, Congress added that November 11th was to be “a day dedicated to the cause of world peace.”

We don’t have so many holidays dedicated to peace that we can afford to spare one. If the United States were compelled to scrap a war holiday, it would have dozens to choose from, but peace holidays don’t just grow on trees. Mother’s Day has been drained of its original meaning. Martin Luther King Day has been shaped around a caricature that omits all advocacy for peace. Armistice Day is making a comeback.

Armistice Day, as a day to oppose war, had lasted in the United States up through the 1950s and even longer in some other countries under the name Remembrance Day. It was only after the United States had nuked Japan, destroyed Korea, begun a Cold War, created the CIA, and established a permanent military industrial complex with major permanent bases around the globe, that the U.S. government renamed Armistice Day as Veterans Day on June 1, 1954.

Veterans Day is no longer, for most people, a day to cheer the ending of war or even to aspire to its abolition. Veterans Day is not even a day on which to mourn the dead or to question why suicide is the top killer of U.S. troops or why so many veterans have no houses. Veterans Day is not generally advertised as a pro-war celebration.

But chapters of Veterans For Peace are banned in some small and major cities, year after year, from participating in Veterans Day parades, on the grounds that they oppose war. Veterans Day parades and events in many cities praise war, and virtually all praise participation in war. Almost all Veterans Day events are nationalistic. Few promote “friendly relations with all other peoples” or work toward the establishment of “world peace.”

In many parts of the world, principally but not exclusively in British Commonwealth nations, this day is called Remembrance Day and should be a day of mourning the dead and working to abolish war so as not to create any more war dead. But the day is being militarized, and a strange alchemy cooked up by the weapons companies is using the day to tell people that unless they support killing more men, women, and children in war they will dishonor those already killed.

The story from the first Armistice Day of the last soldier killed in Europe in the last major war in the world in which most of the people killed were soldiers highlights the stupidity of war.

Henry Nicholas John Gunther had been born in Baltimore, Maryland, to parents who had immigrated from Germany. In September 1917, he had been drafted to help kill Germans. When he had written home from Europe to describe how horrible the war was and to encourage others to avoid being drafted, he had been demoted (and his letter censored).

After that, he had told his buddies that he would prove himself. As the deadline of 11:00 a.m. approached on that final day in November, Henry got up, against orders, and bravely charged with his bayonet toward two German machine guns. The Germans were aware of the Armistice and tried to wave him off. He kept approaching and shooting. When he got close, a short burst of machine gun fire ended his life at 10:59 a.m.

Henry was given his rank back, but not his life.

In a book called Guys Like Me by Michael Messner, the author recounts how much his grandfather disliked Veterans Day: “I tried to cut through Gramps’s cranky mood by wishing him a happy Veterans Day. Huge Mistake.

‘Veterans Day!’ he barked at me with the gravelly voice of a lifelong smoker. ‘It’s not Veterans Day! It’s Armistice Day. Those gawd . . . damned . . . politicians . . . changed it to Veterans Day. And they keep getting us into more wars.’

My grandfather was hyperventilating now, his liverwurst forgotten. ‘Buncha crooks! They don’t fight the wars, ya know. Guys like me fight the wars. We called it the “War to End All Wars,” and we believed it.’ He closed the conversation with a harrumph: ‘Veterans Day!’

Armistice Day symbolized to Gramps not just the end of his war, but the end of all war, the dawning of a lasting peace. This was not an idle dream. In fact, a mass movement for peace had pressed the U.S. government, in 1928, to sign the Kellogg-Briand Pact, an international ‘Treaty for the Renunciation of War,’ . . .

When . . . Eisenhower signed the law changing the name of the holiday to Veterans Day, to include veterans of World War II, it was a slap in the face for my grandfather. Hope evaporated, replaced with the ugly reality that politicians would continue to find reasons to send American boys — ‘guys like me’ — to fight and die in wars.”

A veteran of one of those wars, Gregory Ross wrote a poem called “A Moment of Silence in a Forest of White Crosses.” He wrote it in 1971 to read at a massive anti-war rally at Arlington National Cemetery. It goes like this:

The Dead

do not require our silence to be remembered.

do not accept our silence as remembrance, as honor.

do not expect our silence to end

the carnage of war

the child starved

the woman raped

the virulence of intolerance

the Earth desecrated

It is the living who require our silence

in a lifetime of fear and complicity

The Dead

do require our courage to defy the powerful and the greedy.

do require our lives to be loud, compassionate, courageous.

do require our anger at the continuance of war in their name.

do require our shock at the maiming of the Earth in their name.

do require our outrage to be honored, to be remembered.

The Dead

have no use for our silence

David Swanson is an author, activist, journalist, and radio host. He is executive director of WorldBeyondWar.org and campaign coordinator for RootsAction.org. Swanson’s books include War Is A Lie. He blogs at DavidSwanson.org and WarIsACrime.org. He hosts Talk World Radio. He is a Nobel Peace Prize nominee, and U.S. Peace Prize recipient. Longer bio and photos and videos here. Follow him on Twitter: @davidcnswanson and FaceBook, and sign up for: Activist alerts. Articles. David Swanson news. World Beyond War news. Charlottesville news.