For Media Elites, War Criminal

Henry Kissinger Was a Great Man

Norman Solomon / World BEYOND War

(November 30, 2023) — For US mass media, Henry Kissinger’s quip that “power is the ultimate aphrodisiac” rang true. Influential reporters and pundits often expressed their love for him. The media establishment kept swooning over one of the worst war criminals in modern history.

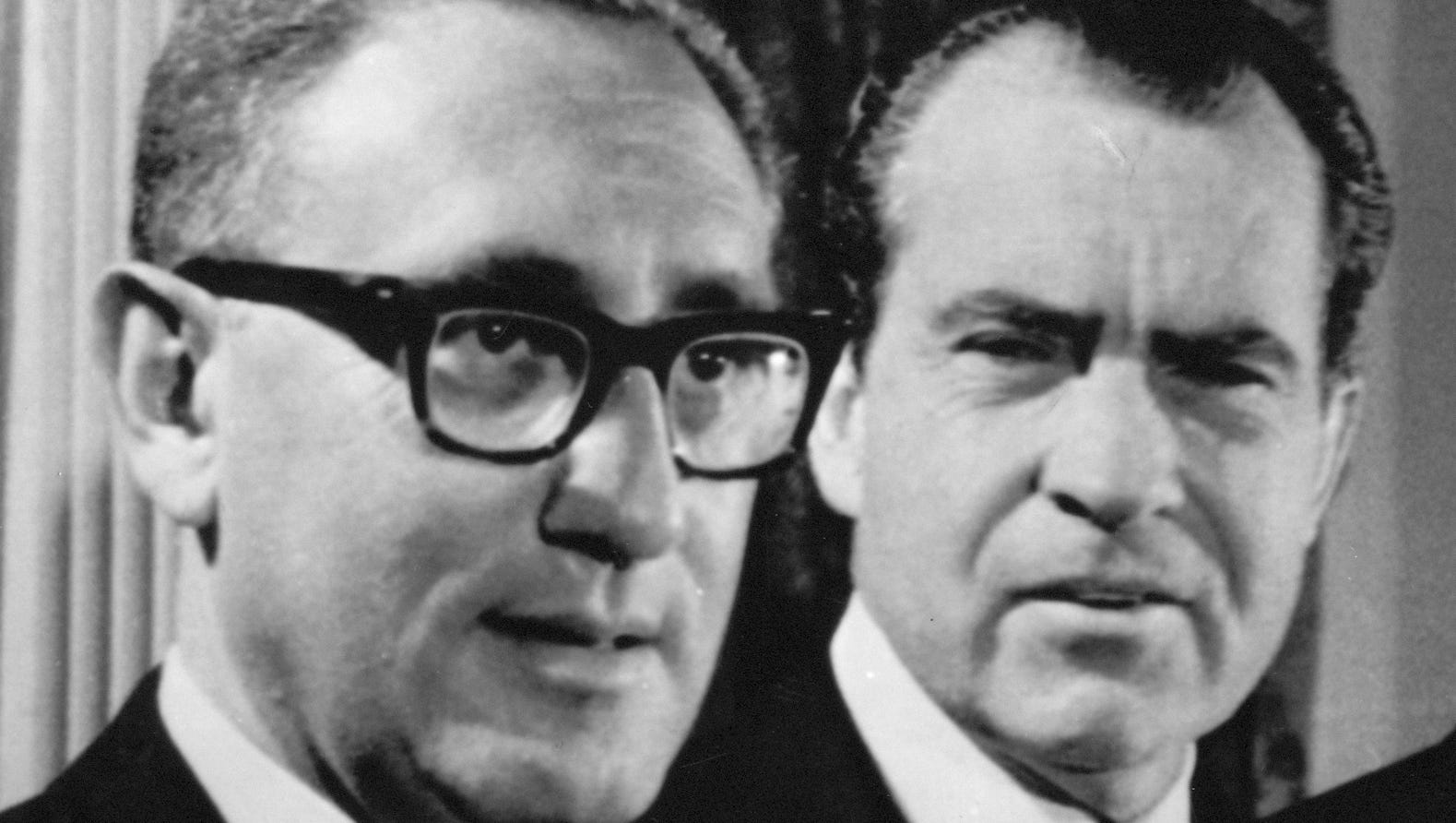

After news of his death broke on Wednesday night, prominent coverage echoed the kind that had followed him ever since his years with President Richard Nixon, while they teamed up to oversee vast carnage in Southeast Asia.

The headline over a Washington Post news bulletin summed up: “Henry Kissinger Dies at 100. The Noted Statesman and Scholar Had Unparalleled Power Over Foreign Policy.”

But can a war criminal really be a “noted statesman”?

The New York Times top story began by describing Kissinger as a “scholar-turned-diplomat who engineered the United States’ opening to China, negotiated its exit from Vietnam, and used cunning, ambition and intellect to remake American power relationships with the Soviet Union at the time of the Cold War, sometimes trampling on democratic values to do so.”

And so, the Times spotlighted Kissinger’s role in the US “exit from Vietnam” in 1973 — but not his role during the previous four years, overseeing merciless slaughter in a war that took several million lives.

“Leaving aside those who perished from disease, hunger, or lack of medical care, at least 3.8 million Vietnamese died violent war deaths according to researchers from Harvard Medical School and the University of Washington,” historian and journalist Nick Turse has noted.

He added: “The best estimate we have is that 2 million of them were civilians. Using a very conservative extrapolation, this suggests that 5.3 million civilians were wounded during the war, for a total of 7.3 million Vietnamese civilian casualties overall. To such figures might be added an estimated 11.7 million Vietnamese forced from their homes and turned into refugees, up to 4.8 million sprayed with toxic herbicides like Agent Orange, an estimated 800,000 to 1.3 million war orphans, and 1 million war widows.”

All told, during his stint in government, Kissinger supervised policies that took the lives of at least 3 million people.

Kissinger and Nixon conspired to topple Chile’s democracy.

Henry Kissinger was the crucial US official who supported the September 11, 1973 coup that brought down the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende in Chile — initiating 17 years of dictatorship, with systematic murder and torture (“trampling on democratic values” in Times-speak).

Kissinger remained as secretary of state during the presidency of Gerald Ford. Lethal machinations continued in many places, including East Timor in the Indonesian archipelago. “Under Kissinger’s direction, the US gave a green light to the 1975 Indonesian invasion of East Timor (now Timor-Leste), which ushered in a 24-year brutal occupation by the Suharto dictatorship,” the human rights organization ETAN reported.

“The Indonesian occupation of East Timor and West Papua was enabled by US weapons and training. This illegal flow of weapons contravened congressional intent, yet Kissinger bragged about his ability to continue arms shipments to Suharto.

“These weapons were essential to the Indonesian dictator’s consolidation of military control in both East Timor and West Papua, and these occupations cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Timorese and Papuan civilians.

Kissinger’s policy toward West Papua allowed for the US-based multinational corporation Freeport McMoRan to pursue its mining interests in the region, which has resulted in terrible human rights and environmental abuses; Kissinger was rewarded with a seat on the Board of Directors from 1995-2001.”

Now that’s the work of a noted statesman.

The professional love affairs between Kissinger and many American journalists endured from the time that he got a grip on the steering wheel of US foreign policy when Nixon became president in early 1969. In Southeast Asia, the agenda went far beyond Vietnam.

Nixon and Kissinger routinely massacred civilians in Laos, as Fred Branfman documented in the 1972 book “Voices From the Plain of Jars.” He told me decades later: “I was shocked to the core of my being as I found myself interviewing Laotian peasants, among the most decent, human and kind people on Earth, who described living underground for years on end, while they saw countless fellow villagers and family members burned alive by napalm, suffocated by 500-pound bombs, and shredded by antipersonnel bombs dropped by my country, the United States.”

Branfman’s discoveries caused him to scrutinize US policy: “I soon learned that a tiny handful of American leaders, a US executive branch led by Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Henry Kissinger, had taken it upon themselves — without even informing let alone consulting the US Congress or public — to massively bomb Laos and murder tens of thousands of subsistence-level, innocent Laotian civilians who did not even know where America was, let alone commit an offense against it.

The targets of US bombing were almost entirely civilian villages inhabited by peasants, mainly old people and children who could not survive in the forest. The other side’s soldiers moved through the heavily forested regions in Laos and were mostly untouched by the bombing.”

The US warfare in Southeast Asia was also devastating to Cambodia. Consider some words from the late Anthony Bourdain, who illuminated much about the world’s foods and cultures. As this century got underway, Bourdain wrote: “Once you’ve been to Cambodia, you’ll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death with your bare hands. You will never again be able to open a newspaper and read about that treacherous, prevaricating, murderous scumbag sitting down for a nice chat with Charlie Rose or attending some black-tie affair for a new glossy magazine without choking.

“Witness what Henry did in Cambodia — the fruits of his genius for statesmanship — and you will never understand why he’s not sitting in the dock at The Hague next to [Slobodan] Milošević.”

Bourdain added that while Kissinger continued to hobnob at A-list parties, “Cambodia, the neutral nation he secretly and illegally bombed, invaded, undermined, and then threw to the dogs, is still trying to raise itself up on its one remaining leg.”

But back in the corridors of US media power, Henry Kissinger never lost the sheen of brilliance.

Among the swooning journalists was ABC’s Ted Koppel, who informed viewers of the Nightline program in 1992: “If you want a clear foreign-policy vision, someone who will take you beyond the conventional wisdom of the moment, it’s hard to do any better than Henry Kissinger.”

As one of the most influential broadcast journalists of the era, Koppel was not content to only declare himself “proud to be a friend of Henry Kissinger.” The renowned newsman lauded his pal as “certainly one of the two or three great secretaries of state of our century.”

Norman Solomon is national director of RootsAction.org and executive director of the Institute for Public Accuracy. He is the author of many books including War Made Easy. His latest book, War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine, was published in summer 2023 by The New Press.

Henry Kissinger, 1923-2023. War Criminal

Robert Reich / Substack

(November 30, 2023) — Henry Kissinger has died, at the age of 100.

When a former high government official as well-known as Kissinger passes, the conventional response is to say nice things about what they accomplished.

I’m sorry, but I cannot. In my humble opinion, Kissinger should have been considered a war criminal.

One telling illustration was Kissinger’s role in overthrowing the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende in Chile, and encouraging the mass murder of hundreds of innocent Chileans.

On September 12, 1970, eight days after Allende’s election, Kissinger initiated a discussion on the telephone with CIA Director Richard Helms about a preemptive coup in Chile.

“We will not let Chile go down the drain,” Kissinger declared.

“I am with you,” Helms responded.

Kissinger and CIA-installed Chilean dictator Pinochet staged a coup that claimed more than 3,000 lives, includindg the death of Chile’s elected president, Salvador Allende.

Three days later, Nixon, in a 15-minute meeting that included Kissinger, ordered the CIA to “make the [Chilean] economy scream,” and named Kissinger as the supervisor of the covert efforts to prevent Allende from being inaugurated.

Kissinger ignored a recommendation from his top deputy on the NSC, Viron Vaky, who strongly advised against covert action to undermine Allende.

On September 14, 1970, Vaky wrote a memo to Kissinger arguing that coup plotting would lead to “widespread violence and even insurrection.” He also argued that such a policy was immoral: “What we propose is patently a violation of our own principles and policy tenets .… If these principles have any meaning, we normally depart from them only to meet the gravest threat to us, e.g. to our survival. Is Allende a mortal threat to the US? It is hard to argue this.”

After US covert operations, which led to the assassination of Chilean Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces General Rene Schneider, failed to stop Allende’s inauguration on November 4, 1970, Kissinger lobbied Nixon to reject the State Department’s recommendation that the US seek a modus vivendi with Allende.

While Schneider was dying in the Military Hospital in Santiago on October 22, 1970, Kissinger told Nixon that the Chilean military turned out to be “a pretty incompetent bunch.” Nixon replied: “They are out of practice,” according to documents released in August by the US National Security Archive.

In an eight-page secret briefing paper that provided Kissinger’s clearest rationale for regime change in Chile, he emphasized to Nixon that “the election of Allende as president of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere” and “your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will make this year.”

Not only were a billion dollars of US investments at stake, Kissinger reported, but so was what he called “the insidious model effect” of his democratic election.

There was no way for the US to deny Allende’s legitimacy, Kissinger noted, and if he succeeded in peacefully reallocating resources in Chile in a socialist direction, other countries might follow suit.

“The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on — and even precedent value for — other parts of the world, especially in Italy; the imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.”

The next day, Nixon made it clear to the entire National Security Council that the policy would be to bring Allende down. “Our main concern,” he stated, “is the prospect that he can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success.”

In the days following the September 11, 1973, coup, Kissinger ignored the concerns of his top State Department aides about the massive repression by the new military regime. He sent secret instructions to his ambassador to convey to Pinochet “our strongest desires to cooperate closely and establish firm basis for cordial and most constructive relationship.”

When Kissinger’s assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs asked him what to tell Congress about the reports of hundreds of people being killed in the days following the coup, Kissinger issued these instructions: “I think we should understand our policy-that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was.”

The United States assisted the Pinochet regime in consolidating, through economic and military aid, diplomatic support and CIA assistance in creating Chile’s infamous secret police agency, DINA.

When Nixon complained about the “liberal crap” in the media about Allende’s overthrow, Kissinger advised him: “In the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes.”

At the height of Pinochet’s repression in 1975, Kissinger met with the Chilean foreign minister, Admiral Patricio Carvajal.

Rather than press the military regime to improve its human rights record, Kissinger opened the meeting by disparaging his own staff for putting the issue of human rights on the agenda.

“I read the briefing paper for this meeting and it was nothing but Human Rights,” Kissinger told Carvajal. “The State Department is made up of people who have a vocation for the ministry. Because there are not enough churches for them, they went into the Department of State.”

When Kissinger prepared to meet Pinochet in Santiago in June 1976, his top deputy for Latin America, William D. Rogers, advised him make human rights central to US-Chilean relations and to press the dictator to “improve human rights practices.”

Instead, a declassified transcript of their conversation reveals, Kissinger told Pinochet that his regime was a victim of leftist propaganda on human rights. “In the United States, as you know, we are sympathetic with what you are trying to do here,” Kissinger told Pinochet. “We want to help, not undermine you. You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.”

The Chilean government has formally requested that the Biden administration publish documentation from 1973 and 1974 on what was said in the Oval Office before and after the coup led by Pinochet.

“We still don’t know what President Nixon saw on his desk the morning of the military coup,” Chile’s ambassador to the United States, Juan Gabriel Valdés, says. “There are details that remain of interest to [Chileans], that are important for us to reconstruct our own history.”

An appropriate response to Kissinger’s death

would be for the US to own up to the entirety

of what Nixon and Kissinger wrought.