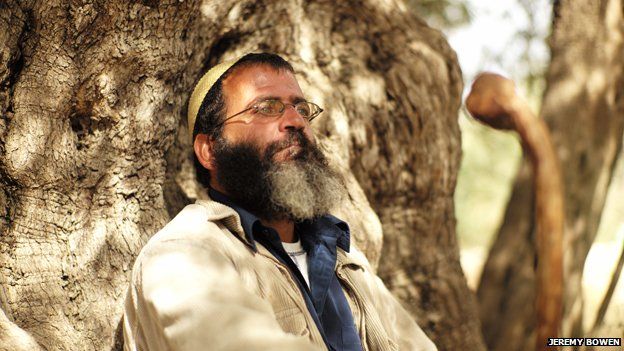

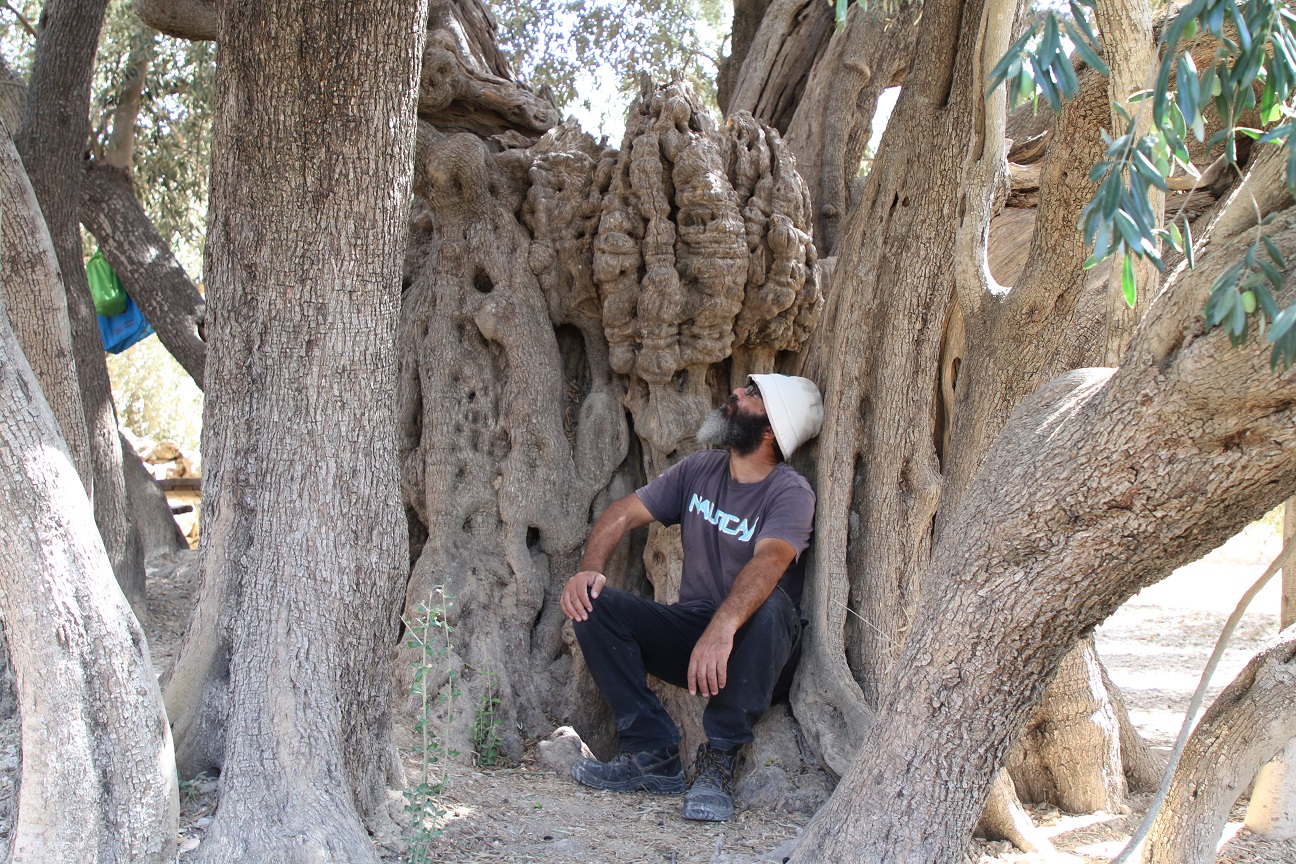

Salah Abu Ali’s tree. “al-Badawi,” was producing fruit long before the Abrahamic religions were born. It is at risk of being destroyed by Israel’s push for land.

Bethlehem’s 5,000-year-old Olive Tree

Is Threatened by Israeli Settlement

George Grylls / The Times

AL-WALAJA (February 19, 2024) — In the West Bank village of al-Walaja, on the outskirts of Bethlehem, there is a tree that is older than any of the Abrahamic religions.

When Moses led the Jews out of Egypt, the olive on Salah Abu Ali’s farm had been producing fruit for almost two millennia.

Three thousand years of rain, wind and drought had failed to kill it by the time of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. And when the prophet Muhammad was said to be first visited by an angel in Arabia in AD610, the tree had long been at the centre of various beliefs held by Semitic-speaking peoples.

The tree has survived droughts, earthquakes and wars. Now it’s under threat from Israeli settlements

In 2010, Japanese and Italian scientists carbon-dated the al-Badawi tree to be between 4,000 and 5,000 years old, which would make itthe second oldest olive in the world after a grove in northern Lebanon. Only its uppermost branches are visible, and the roots are thought to run up to 25m beneath the ground, fusing into a trunk somewhere below the surface.

But despite its longevity, the al-Badawi tree is at risk. For more than a decade, it has been confronted by the encroaching fence of a settlers’ road.

In 2011, Abu Ali’s land was divided in two by the construction of the wall, meaning he can no longer harvest his olive trees on the Israeli side without a significant detour. He relies on the goodwill of soldiers to let him across during the harvest season, something that is not always in ready supply. “It’s a nightmare,” he said, adding that he feared the prospect of another Israeli fence one day cutting him off from his 5,000-year old tree. “Inshallah it never happens,” he said.

The al-Badawi tree’s location is hardly unique, and for decades olive trees have found themselves on the front line of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The Palestinian Authority has accused Israel of destroying 800,000 olives since 1967, and farmers have complained of West Bank settlers uprooting saplings, burning groves, and poisoning roots to claim land in recent years.

An Israeli settlers’ road divides Ali’s land.

In October last year Bilal Saleh, 40, a Palestinian farmer, was shot in the chest by an Israeli settler near Nablus, about 30 miles north of Jerusalem, as he went to harvest his olives. The harvest season has become a flashpoint for conflict in recent years. Given that olives contribute 5 per cent of the Palestinian economy, the financial impact of damage to the harvest is significant.

The al-Badawi tree, which produces olives every other year, still provides a steady income for Abu Ali. He sells olive oil produced from the fruit and when he prunes the branches he sends the wood to craftsmen in Jerusalem. “The tree protects me. I don’t protect it,” he said.

He intends to pass on custodianship of the tree to his four sons, Ibrahim, five, Luhman, seven, Suleiman, ten, and Issa, 12, when his time is done. “We will all die, but the tree will last. We’ve had drought, rains, the Nakba [the dispossession of 800,000 Palestinians who became refugees when the state of Israel was established], earthquake, wars. But it has survived them all,” he said.

The rain falls frequently on the terraces around al-Walaja in February and the almond trees are lush with the smell of blossom. The old train line to Jaffa runs down the bottom of the valley, and the sound of Israeli patrol vehicles driving along the settlers’ road carries up the mountain.

Abu Ali boasts that his village was once known as the larder of Jerusalem because of its fine produce. Al-Walaja was split by the Green Line border in 1949, resulting in the displacement of 70 per cent of Palestinians, including Abu Ali’s family. “Sometimes I just sit and watch the other side of the valley, imagining what it would have been like if we stayed,” he said

Now the village is overlooked by the fortress-like settlement of Har Gilo, and finds itself hemmed in on all sides.

Palestinian farmers live under the threat of demolition orders so that illegal Israeli settlements can be built. Meanwhile, settlements continue to expand into East Jerusalem, where 20,000 Palestinian homes are scheduled for demolition.

“We don’t have licences but they never issue them. If they demolish, so be it. But we will still need a roof. Where will we go? We will build our houses again,” Abu Ali said.

Although he is confronted by political problems today, Abu Ali sees a longer-term threat posed by drier summers, and he recently lost a peach tree and a vine to the stifling heat. Yet even as his other plants struggle, the al-Badawi tree endures. “My olive trees are tough,” he said. “They can handle anything.”

Posted in accordance with Title 17, Section 107, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.